It is easy to forget the past when the present is sweet. In times of India-US warmth, it is worth fleshing out how we arrived here.

Since its early days as a young republic, India has tried to navigate the pressures of great-power politics. The slogan Delhi liked to spout during the bipolar contestation of the Cold War was “non-alignment,” a polite way of saying we too want to be counted as a pole. India’s powerlessness did not matter. Bravado was hectoring major powers in the United Nations on how humbug their policies were. The early Indian leadership under Nehru believed in India’s pre-ordained status as a civilizational state.

The cold reality of defeat in 1962 against China represented a stark lesson for Delhi: rhetoric and arguments at multilateral forums do not count for security. After brief balancing towards the U.S., ideological shibboleths and deep suspicion of the Anglo-American motives drove Delhi away from Washington. That the U.S., misguided by the crafty British, was fattening Pakistan in South Asia was the reigning perception, causing angst in Delhi.

By the early 1970s, India realized that balancing was a part of the game, and equidistance from the two camps made for good speeches, but not sound policy. Under Indira Gandhi, India decisively moved toward the Soviet Union. Consequently, India-US relations hit the nadir; there was hardly an issue the sides could not manage to argue on. The U.S. support for Pakistan in the 1971 war left the relationship tattered if there was any of it in the first place—moreover, India’s perceived willingness to go nuclear outraged Washington. Delhi further slammed the door on commerce. It chucked Coke and IBM out of India. Fear of the foreign hand and “neo-imperialism” were deployed to rally the domestic masses.

Meanwhile, the world order was transitioning to a relatively rare unipolar phase, with America at the top. The disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 also crumbled the foreign policy assumptions Delhi had operated with for decades. It no longer had a benefactor to piggyback on. In 1991, economic ailments at home forced much-needed reform; however, India accelerated trade liberalization before building domestic competencies. Deng Xiaoping’s pragmatism of early internal market reform, followed by trade liberalization after a few years, was not heeded. China had its version of economic reforms 12 years before India.

After India’s reforms, economic engagement finally became one of the driving factors for the U.S. and India to start talking. However, India’s decision to announce itself as a nuclear power in 1998 threw a spanner in the budding relationship. After much diplomatic hankering, ties stabilized for the better. The two sides finally signed the historic civil-nuclear deal in 2008. Even though the practical outcomes of the agreement were negligible, Washington acquiesced to India’s aspirations as an Asian power. Moreover, the U.S. grew uncomfortable with China’s phenomenal rise in Asia – keeping Delhi on good terms helped to balance Beijing.

However, structural suspicions of the U.S. in the Indian bureaucracy and Washington’s misguided overreach overseas convinced India that the quest for a “multipolar” world was the need of the hour. The Russia-India-China (RIC) forum, as well as the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) grouping, were used by Delhi as hedging mechanisms against an overly powerful Washington. Banding with these other emerging powers was intended to ensure multipolarity.

It is in the last decade that India’s strategic illusions are clearing. China has secured its position as India’s primary challenge. A series of clashes at the Himalayan border and Beijing’s growing influence in South Asia have convinced Delhi that Beijing is its primary preoccupation. China’s all-weather partnership with Pakistan, economic undercutting of India, and expansive maritime ambitions have created suspicions about China’s long-term motivations in Delhi.

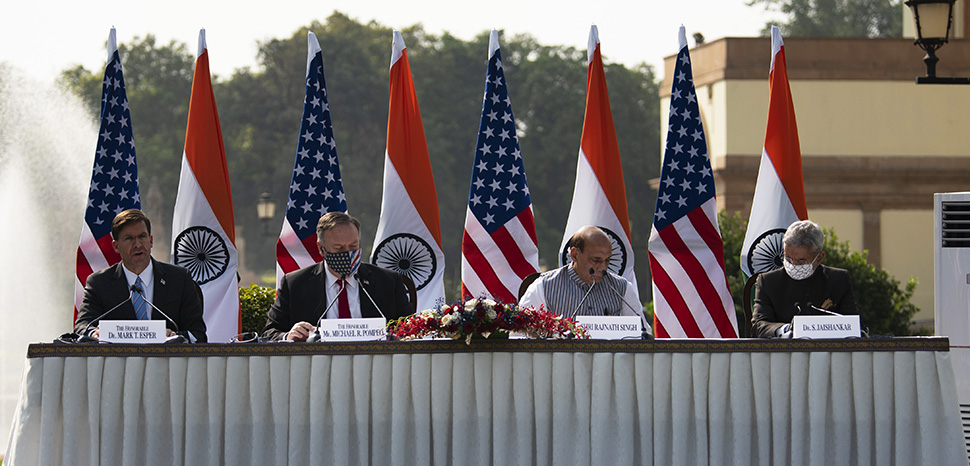

Now when India calls for a “multipolar world,” it makes it abundantly clear that a multipolar Asia is a necessary prerequisite for a multipolar world. In essence, the Asian order is fragmented. The phenomenal rise of China does not mean that Beijing can act like the local mafia. Asia is a playground of contestation, with various emerging and middle powers quietly protective of their identity and sovereignty. The U.S. and India are working together to uphold this reality and ensure stability.

Delhi has also realized that the U.S. is essential for its economic growth. American capital and technology are crucial for India’s transformation. India’s fate in the upcoming decades is inextricably tied to the United States, with or without China as its neighbor.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.