It’s been nearly three months since the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague issued its landmark ruling in the Philippines vs. China case, resulting in a nearly unanimous victory for Manila and a humiliating legal defeat for Beijing in their overambitious assertion of power and authority over vast expanses of the maritime area of the South China Sea.

While China has largely ignored the punitive ruling and deflected minimal damage to its international image, Vietnam and its ASEAN neighbors fear that the most dangerous element of the South China Sea dispute is not island-building, territorial claims, or freedom of navigation, but rather intense competition over rapidly declining fishery resources.

No matter how much self-restraint is exercised by South China Sea claimants, disputes over fishing are part of the daily routine in the region but these combative acts are now exacerbated by China’s large-scale commercial fishing trawlers, regarded by many as an extension of their para-military navy. The clear and present danger in these troubled waters is a looming fishery collapse forcing many fishermen to venture further out into contested EEZs.

While legal scholars are concerned about the transboundary fishing disputes, their spotlight is squarely placed on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Articles 116 to 118 of the UNCLOS deals with conservation and management of the living resources of the high seas. Fish are migratory and fishery resources are indeed exhaustible, so the sustainable use of the South China Sea and conservation of the marine environment benefits all claimants.

Although The Hague’s landmark decision does not deal with claims of territorial sovereignty over land features, namely the rocks and islands, of the Paracels and Spratlys, that are the purview of traditional or customary International Law, it does have indirect effects on the characterization of the land features.

China’s initial non-compliance intersects with their refusal to allow the Philippines fishers to return to their traditional fishing grounds around Scarborough Shoal and their continuing interference with fishers in the region. Naturally, there are far-reaching implications for Vietnam, especially in the land features of the Paracels and Spratly Islands.

No longer can China legally mark its “Nine Dash Line” to claim historical rights on over 80 percent of the South China Sea. Additionally, they must respect and not interfere with the sovereign rights on fishery and marine resources of the Philippines in its EEZ and continental shelf, and cannot do “irreparable harm” to the integrity of the marine environment. This decision does serve to vindicate Vietnam’s geopolitical and legal position presented over the past several years at East Sea workshops.

Since the unification of the two Vietnams, the successor state of Socialist Republic of Vietnam has protested many times whenever there was an encroachment by China, by presenting historical evidence and issuing white papers on the sovereignty of Vietnam over the Paracels and many territories in the Spratlys.

Vietnam’s position has been and remains fixed in these maritime zones, where coastal states are protected in the exercise of their exclusive sovereign rights under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), namely articles 56, 57, 76, and 77. These sovereign rights over natural resources are exclusive to the coastal states, which they can enjoy without being required to proclaim a claim to them, and they may construct artificial structures on rocks, whether submerged or not, into artificial islands, and carry out sea research, regulate protection of environment, provided that they respect the rights of other states to freedom of navigation or to laying of oil pipelines or cables. Other states than the coastal states cannot exploit natural resources in the EEZ and Continental Shelf of the coastal areas without explicit consent.

The tribunal also condemned China’s land reclamation projects and its construction of artificial islands at seven features in the Spratly Islands, concluding that it had caused, “severe harm to the coral reef environment and violated its obligation to preserve and protect fragile ecosystems and the habitat of depleted, threatened, or endangered species.”

UNCLOS has reserved these exclusive rights to coastal states as firmly as a ‘nail hit into a wooden pole,’ sometimes revealed in a Vietnamese proverb: chắc như đinh đóng cột. China’s U-shaped line, which claims vast ocean areas for China, is unsupported by UNCLOS (article 89) that references “No State may validly purport to subject any part of the high sea to its sovereignty”).

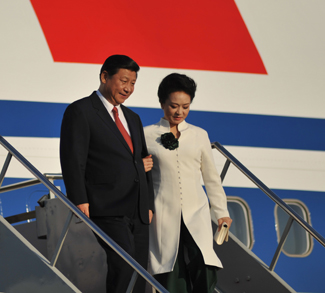

The Chinese president, Xi Jinping’s initial belligerent language after the ruling, flatly stating that “territorial sovereignty and marine rights” in the seas would not be affected by the ruling has suddenly shifted to a low key calm reaction against the award in a strategic effort to avoid defining the historic rights it claims in the South China Sea after the tribunal’s ruling.

Just last month, Vietnam’s Deputy Prime Minister Pham Binh Minh in a UN General Assembly address, urged all parties involved with the South China Sea dispute to exercise self-restraint and solve their problems by peaceful means. Beijing has echoed the same sentiment, stating that ‘common interests between China and Vietnam far outweigh their differences.

The newly elected Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s strident anti-American epithets has for the moment altered China’s hegemonic behavior. The Philippines rift with America now includes canceling joint patrols in their defense cooperation. As a result, China has suspended their implied threats and bullish actions such as building more on Scarborough shoal or on submerged reefs in the South China Sea.

However, some policy analysts suggest that it is Vietnam’s peaceful and stable communication with Beijing that has enabled China’s quiet pivot towards some diplomatic ‘face-saving to negotiation and to legal understanding of international law interpretation. This is supported by China no longer suggesting any withdrawal from UNCLOS. Even China’s Supreme Court issued its own less provocative Hague ruling about the art of better warfare is “lawfare.”

That is why Vietnam concentrates on pursuing legal arguments in their disputed land features and even fishery operations. It certainly helps that The Hague ruled that no feature in the Spratlys is a habitable feature in its natural state, and therefore, no feature is an island as defined in UNCLOS, that would be entitled to a 200- nautical-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

This greatly reduces the allegedly legal ground China has been using for fomenting conflict: the unfounded claim of 200-mile Continental Shelf or Exclusive Economic Zone EEZ emanating from the baseline of some small rocks, which are interpreted by China as islands. The Vietnamese understand the principle of how land dominates the sea. Hanoi’s legal scholars are examining the advisability of presenting a lawsuit for review by the Arbitral Tribunal to confirm the legal status of land features in the contested Paracels.

The recent meeting between Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc and his counterpart, Premier Li Keqiang underscores China’s reassessment and regard for the implementation of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) and a movement toward a Code of Conduct. Vietnam reinforced it belief that it pledges to resolve “maritime issues in a peaceful manner, manage the differences, maintain maritime stability and conduct maritime cooperation in areas of low sensitivity.”

Of course, Vietnam still draws upon numerous historical records from both Western travelers and Christian missionary accounts that support their claims or at the very least presence in the Spratlys and Paracels.

During the existence of the two Vietnams from 1954 to 1975, the role of asserting sovereignty over the Paracels and Spratlys fell on the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) which was entrusted with the administration of both islands, situated south of the partition line represented by the 17th parallel by the Geneva Accords, signed by China and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

A Brief History of Vietnam’s Case for Sovereignty

But the most resounding assertion of Vietnam’s sovereignty over the Paracels was the valiant sea battle the RVN navy fought on January 19, 1974 with the PLA Navy which was sent to occupy the Paracel Islands– for a long time occupied and administered by Vietnam– after China’s announcement of sovereignty over the Paracels and Spratlys on January 12, drawing an RVN protest on January 16 with a request for the United Nations Security Council to take action. This request was repeated on January 20, for yjr UN Security Council to hold an emergency meeting. At the June 28, 1974 UN Conference on the Law of the Sea in Caracas, the RVN repeated its claim of sovereignty over the archipelagos and its protest against illegal occupation by China. On September 24, 1975, at talks with a Vietnamese delegation on visit to China, Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping admitted there was dispute between China and Vietnam on the archipelagos and suggested discussion to settle the problem.

Since the unification of the two Vietnams, the successor state of Socialist Republic of Vietnam has protested many times whenever there was an encroachment by China, by presenting historical evidence and issuing white papers on the sovereignty of Vietnam over the Paracels and many territories in the Spratlys. From 1990-1994 Vietnam once again formally protested— not China’s territorial claim– rather the signing agreement between China’s National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) with Crestone, an American private oil company, permitting the latter to survey in Vietnam’s continental shelf and exclusive economic zone. In 2012 Hanoi again protested China’s overall plan for management of islands.

During the crisis of the oil rig HD-981, from May to July 2014, Vietnam brought to the area surrounding the rig many fishery inspection vessels, the maritime police or coast guard, to demand withdrawal of the oil rig, so as to preserve their sovereign rights. Vietnamese fishermen continued to fish in the proximity, despite the harassment of the Chinese vessels, keeping a safe distance to avoid armed clash, with the purposes of earning their livelihood and asserting national sovereignty in a self-controlled manner.

This maneuver to preserve Vietnamese sovereignty by the international rule of law and deeds has kept intact Vietnam’s claims over Paracels and Spratlys. On the high-tide rocks in the Spratlys that Vietnam continues to occupy and administer since 1976 and before UNCLOS, Hanoi knows all too well, that with thousands of years of living with China that the tides have a natural ebb and flow.

For now, the Continental Shelf, territorial sovereignties, submerged features or low-tide elevations, all part of the seabed, may be put aside. China needs time to absorb its loss of historical ‘face’ and to figure out what the next move is. Let’s hope that all the fishers in the region can patiently and peacefully wait.

James Borton is a senior non-resident fellow at the US-Asia Institute in Washington, DC. He edited The South China Sea: Challenges and Promises in 2015.

Professor Tai Van Ta is a senior research fellow and lecturer at Harvard Law School and is the author of many scholarly books and articles.

Parts of this article were originally submitted at the invitation at an International Workshop held on August 17, 2016 in Nha Trang, Vietnam.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.