In a speech at the UN Security Council, Ambassador Dang Dinh Quy, Permanent Representative of Vietnam, reminded member nations that sea level rise is a major threat for coastal nations, including the lowlands of China, Bangladesh, Indonesian islands, Philippine archipelagos and Vietnam.

Other delegates lauded Quy’s initiative since it signals Vietnam’s preparation for next month’s pivotal climate change summit in Glasgow, called COP26, which is expected to set the course of climate action for the next decade.

The science on sea level rise cannot be ignored in Asia. Millions of lives are situated along coastal waters. For Vietnam, their Mekong River Delta is a vast spread of fertile riverbeds, islets, and mangrove swamps at the end of the Mekong River. It is now among the most vulnerable regions in South Vietnam and home to more than 20 million people, who produce almost half of the country’s rice harvest. One million hectares of land are regularly affected by flooding due to ocean tides. Crops and people’s livelihoods are now at stake.

Even President Nguyen Xuan Phuc has repeatedly called out that climate change threatens global security. In a speech at the UN, he previously sought improved implementation of the UN Charter in international relations and climate adaptation. Still facing the perils of the pandemic, Vietnam plans to borrow around $2 billion to fortify the Mekong Delta sustainably in order to mitigate the effects of climate change.

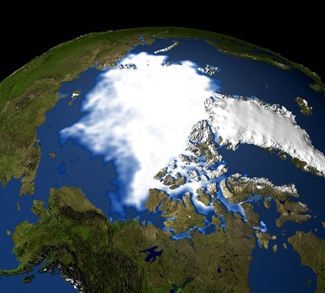

There’s agreement among member nations that sea level rise must be considered a challenge to international peace and security. The source of sea level rise is considered to be a combination of ice-melt from glaciers, ice sheets and thermal expansion from ocean warming. The US National Security Council and the Pentagon warn that climate change will lead to food shortages in some countries that could generate unrest, along with skirmishes over water.

Hanoi’s 2017 resolution on sustainable and climate-resilient development of the Delta aims to increase the rate of ecological farming and to embrace new technologies. “The Ministry of Planning and Investment is developing a ‘master plan’ for the Mekong Delta region for 2021-2030 and 2050 Vision; however, the issue now is how to successfully implement this policy,” says Dr. Nguyen Trung Thang, Deputy Director General of the Institute of Strategy and Policy on Natural Resources and Environment (ISPONRE).

The most recent reports from the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), describes a worrying scenario prepared by more than 100 scientists from over 80 countries. Their evidence confirms that even if there are drastic cuts in carbon emissions, nations like Vietnam face certain high tides. Over the past five decades, Vietnamese farmers have seen sea level rise about 20 centimeters. Also, climate change has led to an increase in natural disasters, especially typhoons, floods, and droughts, which tend to be more severe as well. In short, global sea levels will most likely rise between 0.95 feet and 3.61 feet by the end of this century.

Former Saigon, now called Ho Chi Minh City, with more than 9 million residents, including migrants, continues to experience regular flooding due to increased storms, intense rainfall, and upstream discharges. Of the city’s 322 communes and wards, about half have a history of regular flooding, with 40-50 percent of land in the city less than one meter above sea level.

What’s clear is that rising sea levels amplify storm surge and bring additional chronic threats of tidal flooding. Riverine flooding becomes even more severe with increases in heavy precipitation. The World Economic Forum describes Vietnam’s economy as a “miracle of growth” since it has expanded 6 to 7 percent a year over the past decade. However, during the pandemic Vietnam’s gross domestic product dropped 6.17% on the year for the July-September period, as draconian COVID-19 lockdowns in key areas, including Ho Chi Minh City, led to the first decline since 2000 on a quarterly basis.

Never mind that the city has started construction of a second international airport, a significant milestone as the existing Tan Son Nhat airport handles over 40 million passengers annually. The government’s ambition is to shape HCMC into a financial center in Asia by 2045 and many are already touting it as a smart city by 2025.

A McKinsey report details how the vibrant metropolis’s annual flooding can be compared to a tax on the economy. In their modeling, and use of flood maps, the impacts may amount to about $1.3 billion a year, predominantly from real estate damage. This represents approximately 2 percent of the city’s GDP. Although the city has survived these recurrent floods, anticipated flooding costs will continue to rise, and faster than economic activity.

Rapid expansion has left the city vulnerable to climate change, with an increase in flood levels over the past decade. Overdevelopment and sheer weight of infrastructure in some districts has resulted in the soft soil of the city subsiding. Hydrologists claim that HCMC is now sinking at a rate of 1-2 cm every year as sea levels rise.

Experts believe that Ho Chi Minh City should expect significant disruptions each year, and regular damage could reach $8.7 billion. While real estate damage is still the largest cost, the climate change effects on infrastructure assets such as on the city’s metro, now under construction, may experience further delays associated with intense storms and flooding.

Despite government pledges to spend in excess of $345 million on anti-flood projects, the predicted sea level rise and intense storm surges will require multilateral support, and breakthroughs on adaptation and resilience.

Climate change, including sea-level rise, remains a huge barrier to sustainable development. It also has the potential to affect millions of people around the globe through the loss of livelihoods, infrastructure, and homes and through displacement and an increased risk of statelessness.

In the lead-up to the climate change summit, and with nations running out of time, Vietnam may be well served to share their blueprint for saving the Delta.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com