Contemporary US-China tensions are often likened to the Cold War competition between the United States and the USSR. However, the rivalry also mirrors “The Great Game,” an intense 19th-century contest between the British and Russian Empires in Central Asia. Both empires saw this region as strategically crucial — Britain aimed to protect its colonial interests in India, while Russia sought to expand southward, threatening British India. The “game” involved diplomatic maneuvers, espionage, and occasional military confrontations, with both powers vying for dominance in Afghanistan, Persia (modern-day Iran), and Tibet. The Great Game combined open conflict with subtler tactics like forming alliances with local rulers, espionage, and propaganda.

This new Great Game between the United States and China, much like the original version, is about controlling strategic territories and influence. However, the scope today is far greater, as US-China tensions spill into the fields of economic, technological, and military power, with both nations vying for influence across key regions like the Indo-Pacific and Africa. China is forming economic alliances through initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and BRICS. Meanwhile, the United States has established countless bilateral trade and defense agreements with countries across the Indo-Pacific and Europe, while also leading groupings such as NATO, NORAD, the Quad, the Five Eyes, and AUKUS.

The United States has established 750 military bases or facilities in 80 countries around the world. In contrast, China officially has only one overseas base, in Djibouti, and a permanent naval facility in Cambodia. However, the PLA also operates spy stations in Cuba and Myanmar, as well as a space station in Argentina. The PLA Navy makes frequent ports of call in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and other nations. Beijing is currently courting about 13 countries, trying to convince them to host PLA bases, though most have not yet agreed. Additionally, the PLA Navy and the China Coast Guard are becoming increasingly aggressive in the South China Sea, militarizing and laying claim to disputed territories and islands while threatening global freedom of navigation.

The Great Game between Britain and Russia was often fought between proxies. During the Persian Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911), Britain and Russia engaged in a proxy conflict within Persia, backing opposing factions without direct military involvement. Russia supported the Qajar monarchy and conservative forces seeking to maintain autocratic rule, while Britain, aiming to counter Russian influence, cautiously backed the constitutionalists pushing for reforms.

The PRC’s “no limits” friendship with Russia has turned the Ukraine war into a proxy battle. While Ukrainian and Russian troops are directly engaged on the battlefield, the broader implications reveal a wider geopolitical struggle. The US-led Western order, which includes NATO, the EU, and Indo-Pacific allies like Japan and Australia, supports Ukraine. Opposing them is the emerging China-Russia axis, which is backed by Iran and North Korea, providing Russia with military equipment and funding. The Ukraine war also broadens the scope of the competition, shifting it from the Indo-Pacific to Europe.

The economic dimension of US-China tensions is central to the New Great Game, with both nations vying for technological supremacy, global trade dominance, and influence over international financial institutions. The United States, a leader in both the G7 and OECD, has partnered with Japan and Australia to launch the Blue Dot Network. This initiative aims to promote high-quality infrastructure investment in developing countries, offering an alternative to China’s Belt and Road by certifying projects that meet international standards.

Economic competition between the United States and China is particularly evident in areas like 5G technology, artificial intelligence, and control over critical supply chains. China, through Huawei, has aggressively pushed to build 5G networks worldwide, while the U.S. has pressured allies and partners to ban Huawei’s technology due to security concerns. The rivalry has unfolded across Europe, Asia, and Africa. Additionally, both nations are competing to set global standards for emerging technologies such as AI, quantum computing, and cybersecurity. China’s efforts to influence international bodies like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) are part of its broader strategy to shape global technology standards, while the United States works with allies to counterbalance these moves.

The competition extends to development banks as well. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), led by China, has emerged as a rival to the US-dominated World Bank and the Japan-led Asian Development Bank (ADB). The AIIB finances infrastructure projects across Asia, often in parallel or competition with projects funded by Western-backed institutions.

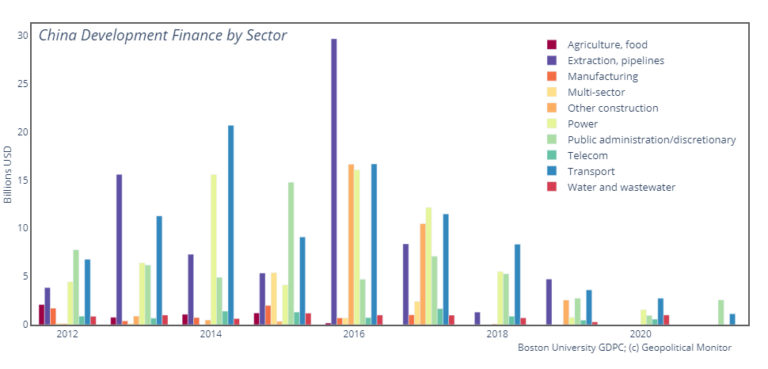

In Africa, China has made significant investments in infrastructure projects, resource extraction, and manufacturing through initiatives like the BRI, securing access to key resources and markets. To counterbalance China’s influence, the United States has launched programs like Prosper Africa, aimed at boosting American investment on the continent and strengthening trade and investment ties. Additionally, the US has reinforced its Indo-Pacific Strategy, focusing on economic and security partnerships with countries like India, Japan, Australia, and Southeast Asian nations. This strategy includes initiatives like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) to counter China’s growing influence in the region. Meanwhile, China has expanded its economic presence in Pacific Island nations, investing in infrastructure, fisheries, and other key sectors.

US-China tensions are shaping up to be a modern Great Game, with both powers maneuvering for influence across the globe. In this new Great Game, China plays the role of Russia, a formidable challenger, while the United States occupies the position of Britain, holding significant global advantages. Just as Britain dominated global banking, currency, trade, and diplomacy—with a vast network of allies and a powerful navy—the U.S. today holds similar strengths. Washington leads in global finance, commands the world’s most widely used currency, and maintains a vast network of alliances, including NATO, the Quad, and AUKUS. The US military, with its extensive network of bases around the world, and the US Navy, a true blue-water force capable of operating anywhere, give it a strategic edge over China’s PLA Navy, which still faces limitations in global reach.

In the original Great Game, Britain managed to secure its interests and maintain control of its prized colony, India, while conceding Afghanistan as a buffer state. Similarly, while the future of this new Great Game is not yet written and the competition is far from over, the U.S., like Britain, has significant advantages over China that could ultimately tip the balance in its favor. But just like the original version, the present outcome is anything but assured, and the stakes are high.