With quite a few scientists and public health experts cautiously optimistic on the likelihood of the COVID-19 pandemic being largely brought to a halt in many countries around the world by the second quarter of 2021, it is worth looking at two sovereign states whose COVID-19 responses have universally been lauded as exemplary: New Zealand and Taiwan. While swift and decisive anticipatory actions by the governments in terms of closing borders, mandating quarantines, imposing lockdowns, and being clear and consistent in the nature of their communication with citizens, coupled with the added benefit of a remote geographical location in the case of New Zealand, were crucial in averting the significantly more disastrous health- and economic-related scenarios seen in most other countries, there are also a number of common aspects pertaining to identity that arguably set the overall tone for the effectiveness of measures taken at the national level.

In the case of New Zealand and Taiwan, three additional ingredients seem likely to have tilted the balance in these states’ favor: a collectivistic mindset of the people, cultural homogeneity combined with well-integrated minority populations, and a preparedness to deal with naturally occurring or human-induced existential threats.

The citizens of Taiwan, similarly to those in other East Asian countries such as Japan, tend to manifest a collectivist orientation of thought, which is likely to result in a willingness to display obedience to public health measures and a motivation to transcend political partisanship. Furthermore, collective solidarity in Taiwan has been amplified by the “triumphal self-liberation from its own authoritarian past” due to the country managing to preserve its democratic system of governance for more than 20 years, putting it in marked contrast to its much larger neighbor to the northwest.

While New Zealand neatly fits Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede’s criteria for an individualist culture, this is tempered by the entrenched egalitarianism that forms an integral part the country’s identity. From the standpoint of the New Zealand government, providing generous wage subsidies was regarded as simply a natural measure to adopt in terms of helping closed businesses shoulder the economic burdens attributable to strict lockdowns. It is thus no surprise that New Zealand hardly saw any discontent stemming from economic issues manifesting itself in direct protest action during the months following COVID-19’s arrival in the country. As a “team of five million,” New Zealanders in all segments of society answered the rallying call to eliminate COVID-19, and the expediency of the project served to bolster national pride.

In addition to the civic solidarity that is easy to activate in the face of adversity, the nature of the majority-minority dynamics in these countries further contributes to strong feelings of national unity.

Taiwan is largely an ethnically homogeneous society (with over 90% of the population consisting of Han Chinese and the major minority group being indigenous Taiwanese) where opposing political allegiances play a more important role in structuring party competition than ethnic divides. Also, this ethnic homogeneity notwithstanding, more inclusive civic conceptions of national identity tend to take precedence over primordially-based ones.

New Zealand’s minority communities, the largest one being the indigenous Māori, are relatively well-integrated into the social and political life of the country. New Zealand is actually somewhat unusual compared to other Western countries in having members of ethnic minority groups (specifically Māoris) display levels of national pride comparable to and even slightly above the national average. Populist politics in New Zealand also invited the participation of Māoris, with the nationalist New Zealand First political party led by Winston Peters, himself of partial Māori descent, and characterized by a hardcore stance on immigration (having on occasions expressed concerns about the levels of Asian immigration into the country) drawing significant support from both Pākehā (White) and Māori New Zealanders. Thus, with a legacy of inclusiveness and the government of Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern unveiling a specific Maori Health Response Plan, Māoris had reasons to feel on the same wavelength as the other New Zealanders and were able to be proactive in combating the spread of the coronavirus. This manifested itself, to take one example, through the operation of “community checkpoints,” which initially courted some controversy, but eventually saw good cooperation between the Māori leaders and the New Zealand police.

Another high-trust society, Sweden, was unfortunate in not being able to replicate the same successes. Issues pertaining to the compliance of ethnic minority communities, such as Somalis, with the COVID-19 prevention guidelines (attributable to linguistic barriers and cultural disconnects) saw members of these groups disproportionately affected and reduced the overall effectiveness of the Swedish strategy that was premised on the following of recommendations issued by scientists rather than sector closures and threats of punitive action by the authorities.

The third commonality between New Zealand and Taiwan concerns the frequent grappling with real and perceived existential threats. An existential threat may reflect true or imagined trepidations that a whole group or aspects of a group’s identity may be annihilated as a result of actions taken by an out-group or caused by natural forces.

In New Zealand’s case, its geographic location (that was beneficial in shielding it from many of the tourist-related coronavirus spikes) in areas of seismic shifts makes the careful monitoring of earthquakes and more recently volcanic eruptions something akin to a national pastime. This has encouraged the country to adopt progressive approaches toward emergency management with regard to natural hazards. It is quite likely that the need to be cognizant of the wide-ranging consequences of such major adverse events has fostered greater discipline and attuned citizens to conscientiously following the protocols outlined by experts.

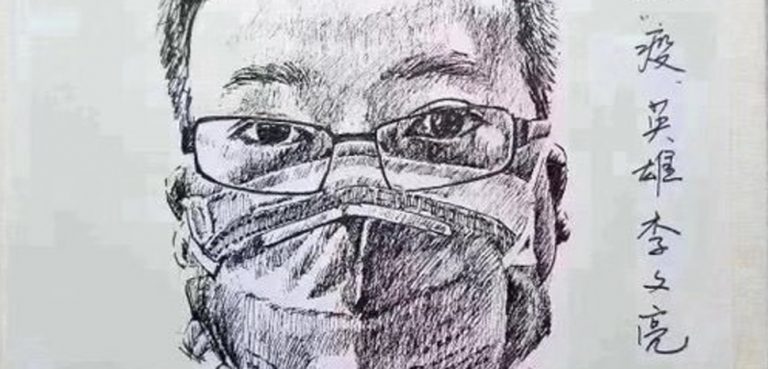

In Taiwan, the idea of the People’s Republic of China as a potential existential threat to its democracy and de facto independence pervades political discourses in the country. This tendency to be extremely attentive to political and social developments in the PRC as well as to meet the official pronouncements of the Chinese government with a heavy dose of skepticism is believed to have produced significant dividends in terms of allowing the country to stay ahead of events in its handling of the pandemic. There are strong indications that as early as December 2020 Taiwanese officials had serious suspicions that the threat of COVID-19 was being deliberately downplayed in the PRC, with Taiwan’s Centers for Disease Control tightening inspections when it came to passengers arriving on flights from Wuhan on 31 December 2019. With regard to health policy and management, Taiwan also benefited from its experience dealing with the 2002-2004 SARS outbreak as well as the lessons learned from the 2009 swine flu pandemic.

Healthy national pride and feelings of national solidarity, a legacy of harmonious majority-minority relations, and a long tradition of tracking and tackling existential threats (without necessarily encouraging the development of a siege mentality) are some of the behind-the-scenes factors that play a part in a country’s success in handling disease outbreaks. While the continued persistence of such cultural patterns should never be taken for granted, it is to be expected that countries that emerge relatively unscathed from once-in-a century challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic will see a further strengthening of their social fabrics.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any institutions with which the authors are associated.