Much as in 2021, when Whitehall released the ‘Integrated Review 2021’ (IR2021) ahead of the Tenth United Kingdom (UK)-Caribbean Ministerial Forum, just days prior to the eleventh such meeting to be held on May 18th in Jamaica, Whitehall has published the ‘Integrated Review Refresh 2023’ (IR2023). Just as IR2021 puts forward a single and contemporary whole-of-government strategy, which is complemented by “numerous other ‘strategies'”, IR2023 constitutes an update of relevant “policy priorities.” It treats holistically with the UK’s national security, foreign and defence policy, and international development approach.

Accordingly, IR2023 will impact the broad sweep and orientation of the UK’s external action in the Caribbean, including the 14 sovereign member states of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), as well as Cuba and the Dominican Republic.

It is not lost on CARICOM that IR2023 will inform London’s priorities in respect of the Eleventh Ministerial Forum, which will bring together UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office higher-ups (among others) and counterparts from Caribbean countries and UK Overseas Countries and Territories in the Caribbean. The Forum’s agenda is still to be finalized.

A May 16th to 17th meeting of the CARICOM Council for Foreign and Community Relations (COFCOR) is expected, among other things, to come up with a coordinated CARICOM position on the upcoming high-level, biennial UK-Caribbean dialogue. No doubt, IR2023 will occupy delegates’ attention at the COFCOR meeting, even as CARICOM is expected to seek to build on the current political accord and action plan between the two sides.

IR2023

Officials would be well advised to consider the difference in approach between IR2021 and IR2023. Whereas IR2021 is reflective of a Brexit moment, representing a landmark in the still young post-Brexit journey of the UK, IR2023 tamps down on its predecessor’s Brexit undertones. IR2023 also glosses over the aftermath of Brexit in respect of the UK’s economy, in a policymaking setting where defence spending has been boosted. It looks with greater purpose at the “geopolitical moment” which Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine brought about.

In short, IR2023 represents the Sunak government’s updating of the British vision of the UK in the wider world. This comes against the backdrop of key security-related trends, which IR2021 previously identified, having accelerated still further. This transpired—just months removed from the publication of IR2021—to a degree that British authorities likely had not anticipated in their associated risk assessments.

It is a vision that in large measure projects the UK’s role as a European security actor, in keeping with the country’s security interests. It is geared towards improving the UK’s global prestige and standing. This reflects this middle power’s self-ascribed outsized role in backing Kyiv in Ukraine’s defiance of Russia, its status as an ever more consequential player in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and a growing rapprochement between London and Brussels. Both London and Brussels, at least by all outward appearances, seem to have turned over a new leaf—following an acrimonious Brexit.

Within this understanding of the geopolitical moment, with its emphasis largely on great powers vying “for dominance in the global order,” Washington (a close ally of London) has gone to great lengths to pit democracies against autocracies. The United States’ (U.S.) Intelligence Community distinguishes between the challenges posed by Russia and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), respectively. There is an undercurrent of sentiment that the Kremlin’s and Beijing’s so-called recalcitrance and revisionist agendas are a threat not just to U.S. interests but, by extension, to those of Western powers writ large—of which the UK forms an integral part.

In this way, the UK’s foreign and security policy outlook is in stark contrast to the PRC’s newly-minted ‘comprehensive national security’ approach and the latest Russian Foreign Policy Concept, both of which are international status-driven. In a context of the escalatory nature of the renewed wave of great-power competition, prominent in Whitehall’s IR2023 considerations are:

- The PRC’s stepped-up, now months-long aggressive actions/provocationsfocused on Taiwan; (this is against the backdrop of the shifting tone of that country’s now blunted three-plus decades-long rise, which must also be viewed through the geopolitical prism of the UK’s ’tilt’ toward the Indo-Pacific—amid Beijing’s growing influence there).

- Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, whose reverberations are being felt across the UK’s securitylandscape, the European security order (forged at the Cold War’s end) and the post-war liberal international order.

‘The Times They Are A-Changin’

In the 25 years since the first Ministerial Forum was held, following a historic decision by the UK and Caribbean in 1997 to strengthen and deepen cooperation via regular and systematized engagements, the two sides have approached security realities and security aspirations careful not to conspicuously bump up against great-power competition. And yet, given the magnitude of its interests in the geopolitical moment, the UK’s calculus suggests that it may have to rethink that approach. In this moment, also considering the China-Russia ‘no limits’ partnership, the UK could stand to lose (to a degree) the influence it has gained from the Ministerial Forum.

As evidenced by their diplomatic signals to Caribbean counterparts, Whitehall mandarins appear to have concerns over the positioning of states of the wider region relative to the dual high priorities of Whitehall, as enumerated above.

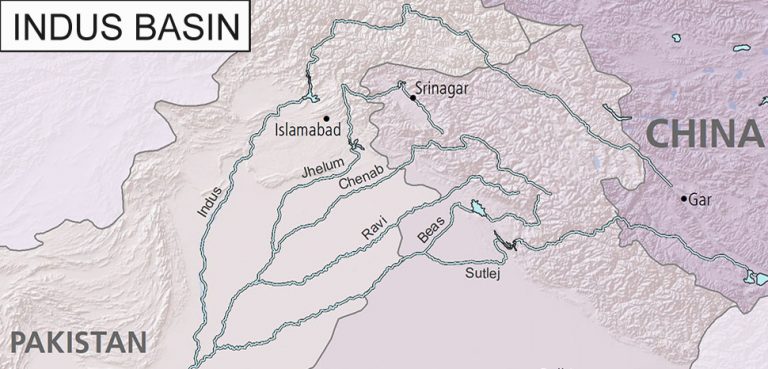

Broadly, London is looking on with concern at Beijing’s “considerable—and increasing—Chinese involvement [in] and engagement [with] the Caribbean states.” (In the case of CARICOM, while five member states maintain formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan (recognizing the island nation as a sovereign state)—which is “a key U.S. partner in the Indo-Pacific”—the others extend diplomatic recognition to the PRC.) Generally speaking, although they are not new, those concerns centre on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI has, though, increasingly come under scrutiny as a vehicle to advance the PRC’s interests, including in the Caribbean. As of 2022, 10 Caribbean countries have come on-board the BRI initiative.

Additionally, London is wary of several risks associated with an initiative that is now under considerable strain; more specifically, calculating how this may translate into Beijing possibly trying to gain or already having gained more political and diplomatic leverage over the states concerned. That the nine CARICOM member states diplomatically backing Beijing have, by and large, steered clear of pronouncing on Beijing’s recent sabre-rattling aimed at Taipei has not gone unnoticed in Whitehall. One of those members of the bloc has gone so far as to say that “the One China policy is important, not just for China, but for the stability of the region.”

This as some Taipei-backers in the bloc, among them St. Vincent and the Grenadines and, more recently, Belize, have conversely stepped up their rhetorical support of Taipei’s independence; at a time when its relations with Beijing are especially fraught with geopolitical danger. Such Taipei-backers tend to draw parallels between Ukraine and Taiwan.

All the while, Havana has backed the Kremlin’s stance on the Ukraine war. London is deeply concerned with Cuba’s positioning in this respect, which the latter adopted fairly early on in the fast-developing conflict.

And the Ukraine war has brought the sovereign CARICOM member states’ into conversation, once again, regarding the United Nations’ (UN) focus on security and peace vis-à-vis “denying legitimacy to aggressive behavior by any state, including the great powers.” As history shows, these small states’ relations with great powers have prompted the former to adopt a course of foreign policy action that either comes into direct confrontation or aligns with the said focus. For example, the bloc fell short in singing from the same hymn sheet on the U.S.-led invasion of Grenada, which the UN General Assembly overwhelmingly deplored at the time—along with the UN Security Council (UNSC)—notwithstanding Washington’s justification. (More recently, against the backdrop of the U.S.’s wider interests, CARICOM member states have been divided in the Organization of American States on “addressing political instability in Venezuela.”) But 20 years later, when it came to the Iraq War, the bloc got behind the previously mentioned focus of the UN.

In an earlier work, which underscores economic development considerations germane to these states’ foreign policymaking, I conclude that the protracted Ukraine war has put to the test the bloc’s commitment to this key focus of the UN.

This is cause for concern for the UK, a bastion of the liberal international order. It could very well underline CARICOM’s democratic credentials as reason enough for the bloc to regard the Ukraine war as a “contest between democracy and autocracy,” resolving to do its part to present a united front.

In sum, this particular geopolitical moment overhangs the Eleventh Ministerial Forum. On the one hand, in this moment, rather awkwardly, the heterogeneity of interests among the wider Caribbean constituency that comprises the partnership has bubbled to the surface. On the other hand, insofar as this moment has stirred up a global north/global south divide that brings into sharp relief the competing interests in play, cooperation in the Forum along these lines could be a tricky business. After all, London is beating the drum about the importance of like-minded partners.

Moreover, just in terms of Whitehall’s corresponding Ukraine war-related adjustments to UK government priorities, an inference can be drawn about how London will likely treat with CARICOM going forward. For instance, in conjunction with a situation of “reduced UK aid spending and the Government’s wider foreign policy intentions to increase UK efforts in Africa and the Indo-Pacific, partly in response to China,” the UK Foreign Secretary has called attention to the need to look beyond “pre-existing friends.” And even though the Foreign Secretary’s recent statement to the House of Commons on IR2023 makes passing mention of the Commonwealth, the UK’s role in international development and its commitment to pursue “patient, long-term partnerships,” it is conspicuous by the absence of any reference to the Caribbean. This should be cause for concern in CARICOM.

Music to Caribbean Ears

Nonetheless, CARICOM policymaking and diplomatic circles are enthused by the UK Small Island Developing States strategy 2022 to 2026, which “sets out objectives to help SIDS adapt to climate change, protect their biodiversity, enhance their access to external finance, and improve their economic resilience and diversify their economies.” They have also welcomed the UK’s stated commitment to “continue to work with [its] Caribbean partners to enhance their economic resilience and ability to adapt to climate impacts, including through direct support [via various] initiatives.”

In addition, the 2022 UK aid strategy’s emphasis on and prioritization of climate change and biodiversity have been well received by CARICOM, which comprises small island and low-lying coastal developing states, especially as Whitehall officials have played up the UK as being well placed to support the region’s climate-related “needs and asks.” (In a significant way, there is carryover to IR2023.) Such signals seem propitious, as CARICOM is playing an increasingly important role in global climate governance and related action. In this regard, the bloc is exercising a leadership role in marshalling an agenda for and action around the climate crisis.

Such international actors have no other choice but to do so. This is because the prevailing circumstances undermine the national interests of and continuously raise the stakes for virtually all CARICOM member states, not least because they are confronted by “debt and climate emergencies” and for whom resilience-building is key.

Against this backdrop, unorthodox policy solutions are required, the likes of which Barbados—a leading member of the bloc—is at the forefront of promoting through international cooperation and multilateral processes. Indeed, Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley has emerged as a leading voice among those making the case for sweeping reform of the global financial architecture. In these political and diplomatic circles, such calls are amplified by debates around climate finance and concessional financing. For instance, they have given impetus, among other things, to a climate change-themed, Paris-hosted summit carded for June, whose sights are set on advancing a New Global Financial Pact.

As their interests and future are most at risk due to the multifaceted nature of this crisis, lending to a so-called “uncertainty complex,” CARICOM member states are rightly at the forefront of international efforts to address this challenge, which they view in existential terms. Prospective British support of such efforts can only strengthen CARICOM’s hand on the international stage, helping to drive impact in international climate-related policy. Securing British support should therefore be a key CARICOM objective going into the Eleventh Ministerial Forum.

What Else to Watch for regarding CARICOM Interests, Expectations

CARICOM member states’ delegations are also expected to call for the Eleventh Ministerial Forum to make headway on other matters at the heart of contemporary UK-Caribbean relations. They include the implementation and operationalization of the CARIFORUM-UK Economic Partnership Agreement, which is a trade continuity agreement arising as a result of Brexit. There is also a strong interest in encouraging UK investment in the Caribbean. The UK’s private sector is exuberant about Guyana’s new and booming oil and gas sector, which international relations experts contend Western powers are thinking about in terms of “[t]he need [in the current international environment] for energy security.” In light of its energy security priorities, at a time when Europe’s energy security is also the subject of intense focus vis-à-vis the loss of the continent’s peace dividend, the UK is a demandeur in this policy area.

For its part, CARICOM has adopted a strategy on advancing energy security. This in a policy context where heads of government have “agreed to increase focus and investment in energy security by utilising and harnessing hydrocarbon resources in the region towards reducing dependency on external resources and supplying the growing global needs arising out of the Russia-Ukraine conflict.”

These matters, among others, are likely to see a push at the Ministerial Forum, not least because both sides coalesce around them.

Some other issues remain a work in progress. For instance, there is the question of the desirability of wider visa-free travel for Caribbean nationals visiting the UK.

Haiti’s “multi-dimensional crisis,” which the UNSC is “keep[ing] under continuous review,” is also of concern. The Ministerial Forum will surely take this matter up.

Finally, the united Caribbean view on the need for reform of the UNSC may come up for discussion. Possible diplomatic manoeuvring, on the part of the UK delegation, on the Ukraine war could be met by the Caribbean side calling attention to prevailing criticism of the Security Council. The geopolitical moment has sparked a resurgence of interest in UNSC reform.

On Balance

It certainly is the case that some of what London has telegraphed in the lead-up to the Eleventh Ministerial Forum has given the Caribbean side pause. But there is reason for optimism, in answer to the underlying question, ‘Can this Forum deliver?’ Set against the promising climate-related meeting of the minds over the years between the UK and Caribbean sides, which are seized of the dire assessments of and recent gains in associated international efforts, the Forum holds promise to move the partnership forward and strengthen requisite action by all parties concerned. And then there are the expected cumulative gains associated with advances in other policy areas, as highlighted above. In short, the partnership should benefit from progress foreseen in those areas. Strides in giving effect to the above-mentioned action plan must also be taken into account.

However, one or both of the sides may find that the security-related considerations of this geopolitical moment could have a bearing on the dynamics of cooperation. In this reading of the upcoming deliberations it becomes apparent that, in this moment, the notion of stretching the conventional understanding of the parameters within which UK-Caribbean partnership talks take place is as much a Caribbean interest as it is a UK interest. But the reasoning behind such a diplomatic scenario has different motivations and geoeconomic-cum-geopolitical end goals, which align with the respective sides’ distinctive national interests.

That said, for some CARICOM foreign policy insiders, the UK’s determination of its geopolitical priorities vis-à-vis Africa and the Indo-Pacific will be far more influential in regard to the level of cooperation with the Caribbean than the geopolitical sentiments of the moment stemming from the Ukraine war.

Suffice to say, having reached its silver anniversary, the UK-Caribbean partnership is grappling with an increasingly expansive and complex agenda, which warrants a relook into the conduct of the relationship.

Dr. Nand C. Bardouille is Manager of The Diplomatic Academy of the Caribbean in the Institute of International Relations (IIR), The University of the West Indies (The UWI), St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad and Tobago. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of The UWI. The author would like to thank Ambassador Patrick I. Gomes, Ambassador Colin Granderson, Ambassador David Hales and Ambassador Riyad Insanally for their very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.