The new national security team is taking shape, under spotlights. Speculation is turning to the new administration’s foreign policy and defense priorities. Who among these officials will get the lead for drawing up a new National Security Strategy (NSS)? Mandated by Congress, if rarely read by Joe Public, the NSS is a public document that reveals much about intentions. It is also a critical lead to which federal agencies must adhere by degrees.

The last time Donald Trump shaped his “NSS” was 2017. A very smart analyst, Nadia Schadlow—currently at the Hudson Institute—did the work commendably. In a course on strategy at the D.C.-based graduate school Institute of World Politics, my students just carried out a seminar on those 55 pages. Their original assignment in my syllabus, Joseph Biden’s National Security Strategy of 2022, has been relegated to their “optional” readings by the recent election.

Trump’s NSS was confident, even boisterous. Its first line announced intent to “make America great again.” Then followed passages about defeating sub-state enemies abroad, suppressing excesses by such “rogue states” as Iran, and challenging great power rivals.

His team has won any debate there may have been about a new era of “Great Power Competition.” Trump argued that it was such a time, and the United States intended not just to compete but to prevail. The Democratic Party had not talked often in such terms but now they do: The November-December issue of Foreign Affairs has a Secretary of State Anthony Blinken article in which the first line is about “fierce competition.” A later paragraph reads strangely like the Trump platform.

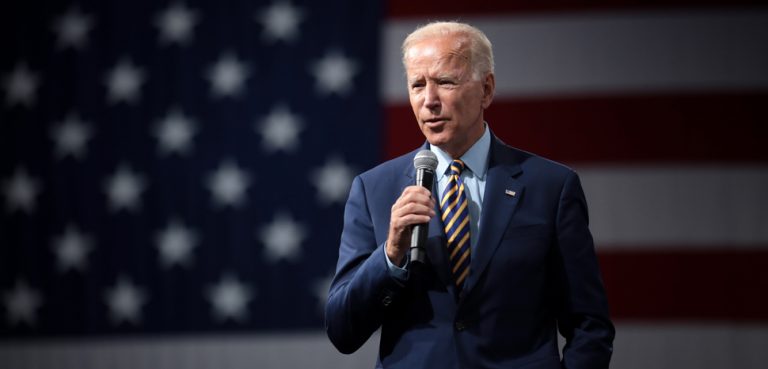

In President Joseph Biden’s 2022 strategy, strengthening alliances was his lead political idea. Biden’s position was that “going it alone” and deprecating North Atlantic Treaty Organization allies was foolish. His NSS anticipated “work in lockstep with our allies and partners…” That is not possible. The larger problem is that after four years, bilateral relations are not better with most countries, save perhaps Japan and one or two more. There have been no improvements with China, India, Brazil, Germany, the United Kingdom, or dozens of others. The same is true with the United Nations, the Organization of American States and the Organization of the African Union and certain other reginal organizations. “Bi-Lats” are worse with Israel—US aid flowed but much opinion there is as icy as the prime minister as to Washington.

Part of the problem, inherent in such strategies, is that of leadership. Consider explicit statements in Biden and Trump’s NSS documents. The latter may have been reckless in that “America First” can readily discourage other countries from following his lead. Mr. Biden declared against efforts “American-led and partner-enabled” in favor of the reverse. But as former Vice President Michael Pence emphasized in a speech here at our Institute of World Politics on Dec. 4, when America won’t lead, he’s found that usually others don’t either.

Certainly, Biden deserves great credit for rushing aid to Ukraine, showing international leadership in forming a coalition for that fight. The crisis was not anticipated when his team composed his NSS but the White House pivoted to it. Trump’s NSS excoriated Islamist terrorism and, much against expectations, assembled scores of international partners to liquidate the ISIS “caliphate” growing like cancer over lands of the Middle East. It’s hard to remember now just how impossible that seemed to most, demanding new military action in Iraq! But the resounding success put action to the words of a dozen past US counterterrorism documents, insisting that terrorist “safehavens” be eliminated.

By tradition, each NSS calls for advancing democracy in the world. For Presidents as different as Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, this was central. The 2017 Trump strategy was indifferent to this idea; he has underscored the dangers of trying to aid democratic forces in Iraq, or Afghanistan, or any failed state. His NSS words on how to “Champion American Values” were few and came at the end; they emphasized being a “beacon of liberty” but not fighting overseas for liberty of others.

Biden’s NSS has more text about fostering democracy, but he’s had few results. The pledge to “support democratic self-determination for the people of Venezuela, Cuba [and] Nicaragua” is now painful to read. Refugees from those three places are flooding into the United States — which obviously drains away voices for reform or revolution in their homelands — one more reason that having no U.S. border is a terrible idea. As for Nicaragua, the man who seized power there in 1979, leftist totalitarian Daniel Ortega, remains atop his perch, where he orders things like confiscation of the infrastructure of a respected Jesuit college he deems “terrorist.” No outside state or organization lifts a finger to stop it.

Published National Security Strategies usually err on the side of the bland. Also, they are more like policy platforms (goals) than “strategies” (how to get there). That was less so with the 2017 paper. New vigor impends. Given fresh ideas and necessary updates, the new NSS from this Trump team should retain its structure: the pairing of strongly declarative postures with “Priority Actions” to realize as much of that vision as world realities will allow.

Dr. Harmon of the Institute of World Politics is the author of Warfare in Peacetime (Marine Corps Univ. Press, 2023).

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.