International diplomacy is composed of an endless list of treaties, agreements, memoranda of understanding, among other types of documents between states. As events unfold and national interests and objectives shift, many of these treaties become obsolete, forgotten or replaced by new treaties. One document that is in the edge of becoming obsolete is the Inter-American Reciprocal Assistance Treaty (Tratado Inter-Americano de Asistencia Recíproca: TIAR), commonly known as the Rio Treaty.

A product of the Cold War, the TIAR has been invoked around 20 times since it was signed in 1947. However, the Treaty is no longer suitable to the realities of defense and security challenges in the Western Hemisphere in the second decade of the 21st century, as the document focuses on inter-state conflicts, particularly the possibility of an extra-hemispheric power attacking the Americas. Thus, the TIAR should be expanded to address new challenges, specifically illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

A brief history

Let us begin by briefly summarizing the TIAR, which was signed in 1947, and entered into force in 1948 – the same year that it was registered at the United Nations. As of 2021, there are 18 signatories to the TIAR, half the Western Hemisphere nations (35 in total). The Bahamas was the last nation to sign and ratify the treaty, in 1982.

Several nations have also withdrawn from the Rio Treaty, like for example Mexico in 2004. Moreover, in 2012, four countries – Bolivia, Cuba, Ecuador and Nicaragua – withdrew. Venezuela withdrew from the TIAR in 2013, but it returned 2019, though we should mention that the governmental body that voted to return to the TIAR was the formerly opposition-controlled National Assembly, not the government of President Nicolas Maduro.

As for TIAR’s objectives, it is generally regarded as a Western Hemisphere-version of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and its famous Article V, as TIAR promotes hemispheric defense and cooperation among Parties to the treaty if one Party is attacked. Article III of the TIAR states that “the High Contracting Parties agree that an armed attack by any State against an American state, will be viewed as an attack on all American States, and consequently, each of the [Parties to TIAR] pledges to help against this attack,” under the banner of legitimate “individual or collective” defense, as recognized by Article 51 of the United Nations Charter.

The treaty was invoked during the Cuban Missile Crisis, though it was not invoked during the Falklands/Malvinas War of 1982 between Argentina and the United Kingdom, in which Washington cooperated with London. After the end of the Cold War, the TIAR was invoked after the 9/11 attacks against the US. Most recently, in 2019, TIAR was invoked against Venezuela, due to ongoing violence and protests in the South American nation between President Nicolas Maduro and President Juan Guaido, and their respective supporters.

Current challenges

While TIAR has been invoked in the 21st century, most recently less than two years ago, it would be wrong to assume that the document is highly relevant to hemispheric geopolitics. The document is designed to protect Parties from armed aggression by non-Parties. However, a wide interpretation of TIAR has allowed for it to be invoked in what is really an internal dispute, namely the situation in Venezuela.

Moreover, it is worth stressing once again that the spirit of TIAR, when it was created in the late 1940s, was to protect State Parties in the Western Hemisphere from an extra-regional threat, namely the Soviet Union.

However, the situation has changed since the Cold War. Inter-state warfare in Western Hemisphere is increasingly rare, the last conflict was between Ecuador and Peru in 1995, while the second-to-last conflict was the 1982 Falklands/Malvinas War. While some border disputes continue to exist, in addition to occasional incidents and tensions, regional governments prefer to look for non-violent ways to solve their disagreements. For example, Colombia and Nicaragua have turned to the International Court of justice to solve their maritime border dispute.

Thus, while TIAR can still be utilized to address inter-state warfare, this scenario is very unlikely to occur in the foreseeable future. Moreover, there have been occasions when State Parties to the TIAR do not respect the document.

IUU fishing

Looking to the future, one possibility is to expand TIAR by adding Articles that expand its responsibilities. Case in point: State Parties should consider utilizing the TIAR to deal with specific transnational crimes, like for example illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

IUU fishing is a complex, global problem. While we cannot analyze in detail its causes and consequences, we can divide this problem in three levels:

National Level. For example, a fishing vessel registered in Peru, whose crew live in Peruvian territory, operates without authorization in Peruvian waters. This is generally artisan-level fishing.

Transnational, Regional Level. This occurs when Latin American fishing vessels cross international waters to operate in a neighboring state. For example, in mid-2020 a fleet of 19 fishing vessels from Brazil crossed into the territorial waters of neighboring Uruguay and operated there without authorization.

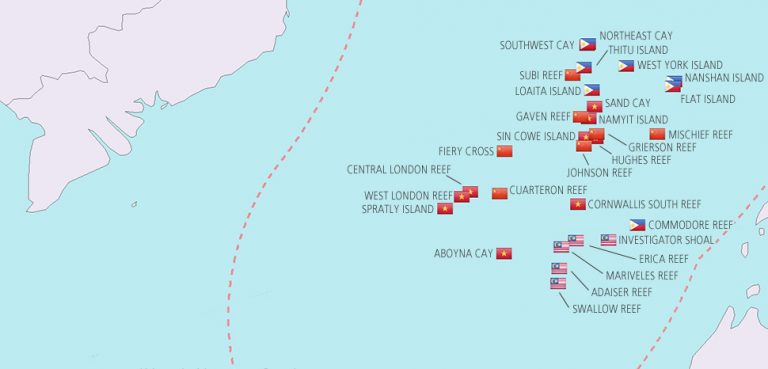

Extra-hemispheric Level. Distant-water fishing fleets from nations like China, South Korea, Spain or Taiwan cross the Pacific and Atlantic and operate in international waters, often crossing, without authorization, into the Exclusive Economic Zones of Latin American nations (see the Stimson Center’s 2019 report, “Shining a Light: The Need for Transparency across Distant Water Fishing”).

These incidents make international media headlines with regularity, particularly as many of these ships come from China. In mid-2020, an international distant-water fishing fleet, with many ships of Chinese origin, operated in international waters close to Ecuador, including the Galapagos Islands. The fleet then traveled South, sailing close to Peru and Chile. According to Chilean authorities, many vessels crossed Cape Good Hope and the Magellan Strait to reach the South Atlantic, operating close to Argentina. An April 2 report by the news agency Infobae describes an international fishing fleet currently operating in the area as a “city of lights” that is destroying Argentine waters.

Warships, submarines, coastal patrol vessels, in addition to maritime patrol aircraft from affected nations have been deployed to monitor this large fishing fleet and ensure that ships do not cross into national EEZs. Of course, given the size of the fleet, even if any of these nations deployed their entire fleets just for surveillance operations, it would still not be enough to shadow each fishing vessel. The aforementioned Infobae report notes that both the Argentine navy and coast guard (Prefectura Naval) do not have sufficient resources to properly patrol Argentina’s vast EEZ. It is worth noting that Argentina is in the process of receiving four offshore patrol vessels, manufactured by the French shipyard Naval Group, but many more naval platforms are required to dramatically improve patrol and interception operations.

IUU Fishing, the future of the TIAR?

As the international fishing fleet operated close to Ecuador and voyaged southwards in 2020, Latin American governments affected by IUU fishing, partner nations, and environmental agencies published the predictable press communiques condemning these fishing vessels, IUU fishing, and pledged to promote cooperation, including intelligence sharing to monitor the vessels.

With that said, regional states should consider taking a step further and creating some type of ad hoc regional task force to monitor extra-regional, distant-water fishing fleets. This could be done by reforming and expanding TIAR to deal with this task.

Article 9 of TIAR mentions what type of actions can be defined as “acts of aggression,” which notably does not include environmental crimes like IUU fishing, hence this Article could be expanded.

It goes without saying that adding IUU fishing to the TIAR would be a gargantuan process. As we have mentioned, IUU fishing does not occur only due to extra-hemispheric fleets. Hence, one obvious concern is that countries could start invoking TIAR against their neighbors over IUU fishing incidents, which would make the situation impossible to handle. Thus, it should be clear that the reforms of TIAR must be oriented towards combating extra-hemispheric fleets – which of course poses another challenge, namely figuring out where these ships come from. Another issue would be properly delineating the EEZs of State Parties to TIAR, which could require solving border disputes.

Moreover, updating TIAR would not be easy or quick. Negotiations would take months, if not years, to ensure that all 18 Parties are in agreement over how expand TIAR and the proper phrasing of the new Article(s). Some governments may also have reservations that they will want to add to the final document before signing.

In spite of these issues and potential conflicts, reforming the Rio Treaty remains a good idea not only to give new life to this document, but also to help Latin America combat an ever-growing threat.

Conclusions

The Inter-American Reciprocal Assistance Treaty is a Cold War-era document that needs to be updated. Inter-state warfare, the original focus of TIAR, is becoming increasingly rare in Latin America. Moreover, applying TIAR to internal conflicts rooted on governance issues, like what is happening in Venezuela, is a complicated issue. Hence, it would be advisable to re-orient TIAR to challenges that governments, militaries and populations across the Western Hemisphere see as a security concern, and source of indignation and anger: illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

Wilder Alejandro Sanchez is an analyst who focuses on geopolitical, military, and cybersecurity issues in the Western Hemisphere and post-Soviet regions. Follow him on Twitter: @W_Alex_Sanchez.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any institutions with which the author is associated.