The apparent interventionist success story of a joint French-Malian military force driving Islamists out of northern Mali was suddenly interrupted this week by a suicide bombing in Timbuktu. The bombing was the first volley in what turned out to be an all-out attack on the city by Islamists, and after several hours of intense street fighting, Malian forces had to call in French troops and air support to help them drive the rebels back into the surrounding desert. The day-long battle left three rebels and one Malian soldier dead, but perhaps more importantly, it afforded the Islamists another valuable opportunity to infiltrate into the heart of Timbuktu.

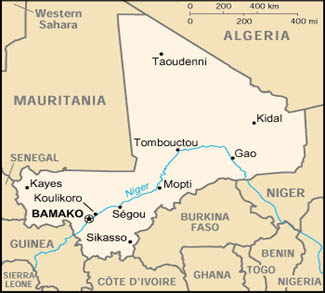

This was not an isolated event. A similar clash took place on March 21st, when a car bomber targeted the Timbuktu airport, again serving as a prelude for a wider assault on the city. And in Gao to the east, suicide bombings and surprise attacks are becoming commonplace.

While the military advantage currently belongs to the French-Malian contingent, the conflict in Mali is starting to resemble a marathon rather than a sprint. Islamist forces, primarily under the banner of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), appear to have taken a page from the guerilla handbook by not attempting to hold any territory, launching surprise attacks to demoralize and inflict heavy casualties, and melting back into the surrounding countryside whenever faced with superior firepower.

It won’t take too much pressure to break the political will for intervention, particularly with regards to France, which is already planning its own exit. French President Francois Hollande declared that France had ‘achieved its objectives’ in a television interview this week, and set a withdrawal timetable for drawing back France’s current 4,000 troops to 2,000 by July and then 1,000 by the end of the year. Withdrawals are scheduled to begin sometime next month.

Islamist forces in the north can thus bide their time in the confidence that they’ll be facing a weaker opponent a few months from now. Yet there still is a question of who exactly that opponent will be. A UN-backed force of around 6,300 troops from various West African countries (known as AFISMA) has been deployed in Mali to help take over from the French. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has also referred the issue to the Security Council, recommending that AFISMA be converted into a UN peacekeeping deployment and that a parallel force be created to “deal with Islamist threats directly.” Such a force would likely be composed of the roughly 1,000 French troops that are expected to stay behind in Mali.

Questions of composition aside, the peacekeeping force will be charged with a difficult task. Islamists can infiltrate northern cities and slowly sap the political will and operational capacity of occupying soldiers via attrition. Moreover, it might be difficult for occupying forces to earn the trust of local populations – not out of any love for the Islamist cause, but out of fear of reprisals should the north once more fall into the hands of AQIM. The people of northern Mali are doubtlessly aware that their political future depends in large part on the whims of foreign parties, whether it’s France, the West African countries of AFISMA, or the members of the UN Security Council.

The most effective solution happens to be the most daunting as well, which would be reestablishment of a civilian government in Bamako that can fill the power vacuum in the north and drive AQIM out for good. Recall that the 2012 coup that originally triggered the current instability sought independence for the Tuareg people in the north. These sectarian divisions did not disappear after AQIM took over; they just faded into the background.

Now that AQIM is in retreat, the north-south divide can once more come into focus, extinguishing any credible hope of a strong federal government emerging from elections scheduled for July. In the north, Tuareg separatists belonging to the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) have picked up where they left off before being elbowed out by the Islamists, and they are said to be issuing security passes in the name of the Azawad Republic in the region surrounding Kidal. In the south, pitched battles are breaking out in the streets of Bamako, such as the one that occurred on April 30th when two branches of the Malian armed forces began firing on each other over rumors that a military leader was about to be arrested.

Given the complex web of sectarian divisions and bureaucratic loyalties at play in Mali, it’s unlikely that elections will be the salve needed to bring the restive north under control. In this context, the successful French-Malian intervention and France’s impending drawdown should not be viewed as the end of the war, but merely the beginning of a long, drawn-out guerilla conflict in the north.