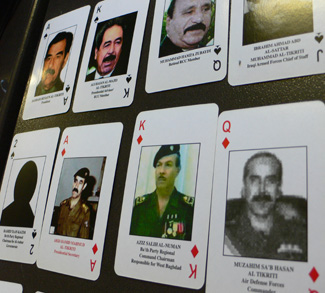

In his 2010 Hollywood film Green Zone, director Paul Greengrass addresses the US Army’s failure to locate weapons of mass destruction in Iraq in the weeks immediately following the 2003 invasion of that country. Greengrass also touches down on one of the chronic problems that has affected Iraq’s governability since the Anglo-American led war: the disbanding of the Iraqi army by Paul Bremer, President G.W. Bush’s special envoy and de-facto ‘viceroy.’ In an early scene, the character ‘General Mohammed Al-Rawi,’ likely inspired by the real life General Ayad Futayyih Khalifa al-Rawi, the ‘Jack of Clubs’ in the US deck-of-cards style most wanted list of Saddam Hussein loyalists, is fictionally shown to be willing to join the US armed forces in helping to maintain order in the country in the aftermath of the invasion. In reality, thousands of well-trained Sunni officers found themselves out of work and their livelihoods destroyed at the stroke of Bremer’s pen. At that time, America created some of its worst enemies; indeed, that was when the roots of ‘Islamic State’ were planted.

The movie was intended as a criticism of the Iraq war, the way the occupation of Iraq was managed, and the supine media coverage. It raised some important questions about the fate of the key military figures in Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime. Since the 2003 invasion, Iraq has only namely become a ‘democracy.’ In reality, the country has never recovered from the rise of religious factionalism as Shiites have replaced Sunnis as the dominant religio-political community. Islamic State, emerging from Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Daish/ISIS) and itself from Al-Qaida in Iraq is one of the direct consequences of the US invasion, and behind the success of its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi lurks the influence of several high level officers who served under Saddam Hussein. Indeed, the Islamic State leadership includes officers, secret agents and counterterrorism officials from the former Iraqi regime.

The bewildering spread of ISIS in Iraq and Syria certainly cannot be justified by the religious fervor that animates the fundamentalists alone. Moreover, its hatred for Westerners is not new and it does not explain how such a capillary organization has proven to be far more efficient than the one fielded by government loyalists as well as the formidable foe of some of the world’s most sophisticated military planners. There is no question that professional and well-trained military personnel lurk behind ISIS. The organization has been effective both on the battlefield against armies and in conducting deadly asymmetric warfare in towns and cities. ISIS has displayed a powerful mix of organization and discipline, necessary in keeping jihadist fighters from around the world integrated by terrorist tactics, such as suicide bombings, while performing full-scale military operations worthy of being taught at Sandhurst or Westpoint. Certainly, the fighters fielded by ISIS have proven to be much more disciplined and organized than their Iraqi Army counterparts.

The Relationship between JRTN and ISIS

One of principal figures behind the rise of ISIS and eventually Islamic State is one Saddam Hussein’s former army majors, one Saud Mohsen Hassan, better known by his ‘noms de guerre’ of Abu Mutazz and Abu Muslim al-Turkmani. He was arrested in 2000 and imprisoned in Camp Bucca, the main detention center for members of the Sunni insurgency, which was managed by the United States. This is the same prison that was also home to al-Baghdadi. US military planners and intelligence analysts apparently failed to realize that those prisons could became huge incubators of radicalization, allowing religious extremists to mingle with Saddam’s former officers, including members of the Republican Guard and the Fedayeen paramilitary force. Today, those same men make up the leadership of Islamic state. Abu Alaa al-Afari, a former Iraqi Army officer from the Saddam era, and allegedly once affiliated with al-Qaeda, is believed to be at the head of ISIS’s “Beit al-Mal” (in Arabic ‘the treasury’). Al-Baghdadi also recruited Saddam-era veterans to serve as “governors” in seven of the twelve provinces established by Islamic State in the territory it has conquered in Iraq. To date, some 100-160 Saddam-era veterans occupy key posts in the Caliphate and the CIA says that all officials of the Islamic State come from Sunni-dominated areas. Former Iraqi intelligence officers control the western province of Anbar while former army officers have been deployed to Mosul. Former members of the ‘mukhabarat,’ the Ba’ath’s security services, most of whom hail from Saddam’s clan, are based in Tikrit, the former dictator’s birthplace.

Assem Mohammed Nasser, also known as Nagahy Barakat, former brigadier general of Saddam’s Special Forces has taken on a leading role in ISIS since 2014, he ‘distinguished’ himself during the assault of Haditha in Anbar province, where 25 policemen were killed. Perhaps the most emblematic case is that of Mohammed Samir Abd al-Khalifa, also known as Haji Bakr, a former colonel of the air force secret services under Saddam Hussein. The German weekly Der Spiegel has published a number of secret documents in its possession revealing al-Baghdadi’s military strategies and ISIS’s hierarchical structure. Al-Baghdadi’s fighters and members of JRTN (acronym from the Arabic name Jaysh Rijal al-Tariqa Naqshabandiya, the ‘Army of the Men of the Naqshbandi Order,’ identifying Saddam Hussein’s military entourage) were united by their aversion to the Shiite government of Al Maliki and a desire to regain what was taken away from them by the United States’ military intervention. But ISIS and JRTN are not natural allies. The differences within the two organizations are in fact many, deep, and increasingly obvious. If ISIS wants to erase the boundaries of today’s Iraq – and Syria – to build an Islamic state on the ashes, the latter represents a largely secular and progressive movement that would restore the supremacy of the Ba’ath party in Iraqi political and civic life, the party that held power for roughly four decades before the US invasion of 2003. This suggests that ISIS itself contains the seeds of its own destruction and that the prospects of a prolonged ‘civil war’ in Iraq between the current Shiite-dominated government and Sunni forces are sadly all too real, especially considering the emboldened influence of Iran in the wake of the nuclear deal. This is why it is so important to prompt a deep discussion between Iran and Saudi Arabia if any initiative of value is to be adopted.

ISIS’s relentless violence – which already earned al-Baghdadi the scorn of other jihadist groups operating in Syria – is another crucial point of friction between himself and the JRTN, which has denounced the massacres terrorist organization and in particular the persecution of religious minorities such as Christians in Iraq and Yazidis in Syria. Christians lived quite well in Saddam’s Iraq and one of the best known figures of his regime abroad was Tareq Aziz, a Chaldean Catholic who occupied such posts as minister of foreign affairs and prime minister. He died last June in jail. It is worth noting that the Ba’athist dictatorship punished with an iron fist those found fomenting religious wars. Doubtless, the tensions between Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds were buried under the surface only to emerge whenever the regime was distracted with external threats. But despite the secular penchant, Sunni clans in the region of Tikrit enjoyed privileges in Baghdad’s ‘politburo.’ Formally there were no differences of creed or ethnicity hampering personal ambition. Social ranks under Saddam Hussein could be climbed in direct proportion to one’s loyalty to the dictator and the country.

The story of ISIS, in the true sense of its expansion in the Levant and over the Iraqi border (in Arabic ‘shams’) begins with the arrival of Haji Bakr in Syria at the end of 2012. Until then the words ISIS, let alone “Islamic State” were not yet in the public domain. But Haji Bakr’s plan was clear. He wanted to conquer as much territory as possible in Syria and use it as a bridgehead for the invasion of Iraq. Bakr settled in the town of Tal Rifaat, north of Aleppo, which since the 80s has served as a major source of migrant labor for the Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, where many adopt radical ideas (this is a well known phenomenon, which has also been identified in the context of Islamic radicals in Egypt). Many of these men were recruited to establish the Islamic State. In 2013, Tal Rifaat became an ISIS stronghold with hundreds of fighters. It was there that the “Lord of Shadows,” as some call Haji Bakr, outlined the structure of the Islamic State: from the local level to a gradual infiltration of surrounding villages. Using a ballpoint pen, he drew on a piece of paper the future chain of command of the Caliphate. This was no faith-based arrangement; rather, it was a technically elaborate plan for a caliphate run by an organization that resembles the notorious Stasi, the former DDR’s domestic intelligence agency, which was said to be more effective than the KGB itself.

Meanwhile, Izzat Ibrahim al Douri, vice president in the Saddam era has been identified as one of the masterminds of ISIS’s rise in Iraq. Al Douri was killed on April 18 in Hamrin, a resort town about 40 kilometers northeast of Tikrit. Known for his red beard and mustache, he had been ranked sixth – the ‘King of Clubs’ – on the United States’ most-wanted list. A fugitive since 2003, upon whose head was flung a $10 million bounty, he is believed to have expressed support for the Saudi military last April in their fight against pro-Iranian Shiites in Yemen. The explanation for the odd mix of Baathist secular ideals and Islamic radicals goes back to the period immediately preceding Gulf War of 1990-1991. One of the betraying symbols of this unlikely convergence of interests is the ‘Allahu Akbar’ that suddenly and mysteriously appeared on the Iraqi flag on 13 January, 1991, just three days before operation Desert Shield evolved into Desert Storm. The religious invocation, officially named ‘Faith Campaign,’ was rightly interpreted as an appeal to the Muslim world in general for solidarity, if not support, but few had imagined that Saddam Hussein had also started to fill the highest military ranks with officers whose religious beliefs bordered on the radical – Sunni radical that is, perhaps in expectation that the US bombings and attacks would stimulate a Shiite uprising that did in fact eventually happen. The Faith Campaign deviated from the Baath Party’s principles, but it was seen as the best way to ensure loyalty in the difficult period that followed Saddam’s humiliating defeat in 1991, which loosened pent-up repression among Shiites and other minorities from the Kurds to the Marsh Arabs.

Saddam-era officers have endowed ISIS not just with its effective military tactics, but also with links to tribal leaders, thus establishing a network of support and recruitment. The Faith Campaign got a further boost in the months preceding the 2003 invasion ordered by G.W. Bush, as Saddam Hussein encouraged mujahedeen to set up base in Iraq and fight the Western enemy – many of these fighters received formal military training. Clearly these troops, along with well-placed radical officers, established the backbone of what is now known as the Islamic State.