Summary

The Moon Jae-in administration came to power promising an overhaul of South Korea’s military structures and industries. Due in part to the country’s delicate geopolitical situation – a bellicose neighbor to the north, a rising powerhouse across the Yellow Sea, and a mercurial ally across the Pacific – the effort has received wide support from the public. But can it succeed in making South Korea an independent military player in the region?

Impact

A comprehensive overhaul of the ROK armed forces was announced in July of 2018, dubbed “Defense Reform 2.0.” The program involves political aspects, such as de-emphasizing the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) as an overriding threat, increasing civilian control over the armed forces at all levels, and striving to take over operational command from the ROK-US Combined Forces Command in the near future. It also seeks to impose new operational paradigms, many of reflect the (late) arrival of RMA thinking in the ROK armed forces. For example, in response to dwindling birth rates, President Moon increased wages for enlisted personnel by 88% in an effort to foster greater professionalization. In terms of technology, the plan promotes home-grown missile and satellite surveillance platforms, combat drones, and cyber defense among other platforms. Nearly all of it fits the RMA dictum of quality over quantity – to do more with less.

These reforms necessitate higher defense spending, and the Moon administration has obliged. In fact, President Moon has presided over three significant year-over-year boosts in defense outlays: 7% (2018), 8.2% (2019), and 7.4% (2020). Increased defense spending was an established trend even before Moon assumed office. The Lee Myung-bak era averaged annual increases of around 5%, and the Park Guen-hye era around 4.1%. In terms of defense spending as a percentage of GDP, South Korea has hovered in the 2.25-2.5% range for the past 15 years – well over the 2% threshold that NATO states consistently fail to reach. And in terms of its percentage of overall government spending, South Korean defense spending is even higher relative to some of its peers: 12.7% in 2020, compared to 9.2% in the United States and 4.5% in the UK.

Reinvigorating South Korea’s defense exports

As a major arms exporter, any push to develop new home-grown platforms has a significant economic dimension in that it creates new, non-tradable jobs. South Korea has become a regional powerhouse in the arms trade, with exports growing from $253 million in 2006 to $2.5 billion in 2016. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute currently ranks it as the 10th largest exporter in the world, representing 2.1% of total export volume between 2014-2019.

The high-tech focus of Defense Reform 2.0 hints at new export opportunities in the years ahead, when drones and cyber weapons augment traditional strengths of ROK defense industries such as conventional artillery. There’s also some geopolitical subtext here: a push toward high-tech self-sufficiency will reduce the ROK’s dependence on US-made platforms. The country has consistently ranked among the top ten purchasers of US arms, amounting to some $6.28 billion from 2014-2018. Such purchases are not only costly, as they can involve surcharges for research and development; they have also been politicized in the Trump era and linked to the status of US troops in South Korea, albeit indirectly. Though this was likely part of the former US president’s ‘art of the deal’ to make Seoul pay more for US troops based in South Korea, it has been widely interpreted as proof of a not-so-ironclad US defense commitment, and thus of the need to adopt a more self-sufficient and independent defense posture in the future.

Coming soon: A ROK Navy aircraft carrier

One high-profile recent procurement item is the construction of a homegrown aircraft carrier at a projected cost of $1.7 billion. The LPX-II light aircraft carrier’s design was finalized in the final days of 2020 and construction costs have been budgeted through 2024. The ship builds on the design of the LPX-I Dokdo class helicopter carriers, of which there are two currently operating in the ROK Navy. The new carrier is expected to displace around 40,000 tons, and be able to accommodate nine helicopters and 20 F-35B fighters (Seoul upped its purchase of F-35s last year, and is expected to deploy up to 80 of them when all deliveries are complete). By way of comparison, a Nimitz class aircraft carrier displaces 100,000 tons and can accommodate a maximum of 130 F/A-18 Hornets.

The LPX-II aircraft carrier is expected to enter service in 2030.

Toward an independent military posture?

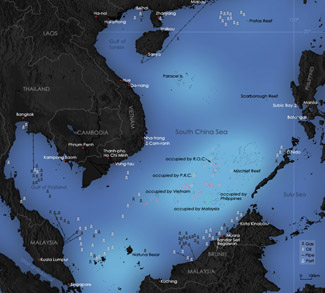

Building an aircraft carrier may seem counter-intuitive for a middle power facing a land-based existential threat to the north, but several factors influenced the decision. For one, there’s the economic incentive along with the potential benefits for South Korean shipbuilding and, down the line, its arms exports. Two, the decision to pursue an aircraft carrier – which was somewhat sudden and was originally expected to be another LPX-I helicopter carrier – allows South Korea to keep pace with Japan, which is already converting helicopter Izumo class helicopter carriers into F-35-capable aircraft carriers. Without its own aircraft carrier, Japan would gain a hypothetical advantage in military maneuvers near disputed territories like the Liancourt Rocks (‘Dokdo’ in Korean), though such a contingency seems far-fetched so long as the two countries remain under the US defense umbrella. Third, it will generate national prestige and ensure that South Korea is not the only regional power left without a carrier (especially important in light of competition with Japan). And fourth, it will bestow the ROK Navy with a ‘blue water’ operational capacity that will allow it to participate in allied offshore military maneuvers on a more equal basis. This final point may come to be the most important depending on how events develop over the next decade, and it should be assessed in the context of initiatives like the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy and the Quadrilateral Dialogue. Should Seoul ever join the Quad (the oft-mentioned ‘Quad Plus’ hints at such a possibility), a carrier capacity would allow the ROK Navy to contribute in a meaningful way. But if not, as currently seems the most likely scenario, the carrier will also provide some leverage against China, which is far more advanced in its own carrier rollout.