The US budget crisis dominating global headlines can be divided into two parts. First there’s the shutdown of US government services, a threshold that has already been crossed, shuttering various federal agencies in the United States. This is not only with historical precedent (a Republican-controlled Congress shut the Clinton government down in 1995 for 28 days), but also predictable given the bitter bipartisan politics that have descended over Washington in the past few years.

But then there’s part two of the crisis: an October 17th deadline for raising the US debt ceiling. Here is an issue with consequences that could transcend domestic politics, whether or not the players involved care to acknowledge it. For an intensely bleak view as to what these consequences might entail, refer to the recently-released US Treasury Department report on the subject. The report describes a failure to raise the debt ceiling as a “catastrophic” event that would lead to a freeze in credit markets, a precipitous drop in the value of the US dollar, and a spike in interest rates, among other economic shocks. To be sure, this would be an event that sent shockwaves throughout the global economy.

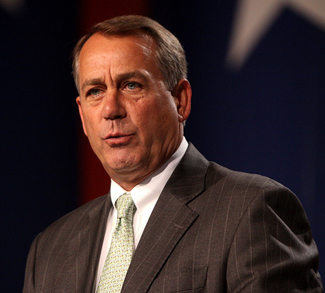

With the economic stakes so high, it’s hard to imagine House Republicans forcing a US government default, especially over a position that isn’t supported by an overwhelming majority of US voters. Unsurprisingly, cracks are showing in the Republican caucus, and House Speaker John Boehner has been able to placate moderate Republicans thus far by passing ad hoc bills sending some government employees, such as those in the Department of Defense, back to work.

Yet on the other hand, domestic crises mirror international ones in the sense that, under pressure of time and events, the most rational course of action doesn’t always prevail. House Speaker Boehner has staked his own political fortunes on the outcome of this impasse, such that a Democrat-weighted political compromise might cost him his position and cast him as the latest victim of the growing ideological polarization of the Republican Party. Either way, a few financial institutions are quietly hedging their bets and purchasing US credit default swaps, contracts that would pay out around $3.4 billion in the event of a US default.

Even if the crisis heads towards its most likely resolution and the House Republicans blink at the last moment, damage is still being done to the US macroeconomic position.

Investor confidence is impacted by policy deadlock in Washington. Recall that it was a similar crisis in 2011 that led to Standard & Poor (S&P) stripping the United States of its AAA debt rating, and though S&P recently announced that it is not considering any further downgrade at present, the ratings agency also asserted that, “this sort of political brinkmanship is the dominant reason the rating is no longer AAA.”

Political brinkmanship and policy deadlock are not just concerns surrounding the (now annual) event of raising the US debt ceiling. If the political process is broken, and rational, bipartisan solutions cannot be found for some of the United States’ structural economic problems, then investors will come to doubt the infallibility of US debt and US Treasury yields will spike, creating fiscal difficulties for future US governments.

Treasury yields are a function of overall demand for US federal debt, demand that is driven by foreign purchasers such as Japan and China, and at the present moment, the Federal Reserve policy of quantitative easing, which is buying up around $85 billion worth of debt every month. The current mix of buyers is resulting in an interest rate of 2.4%, which is particularly low given the 20-year-average of 5.7%. If the current rate were to adjust upwards to the historical average, the US government would face a serious fiscal crunch. In fact, under many Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections, the US government will face a fiscal reckoning at some point in the next decade. Outside factors such as investor confidence in US debt will merely determine the scope of this crisis; or put another way, whether it will even be possible for future governments to make their debt servicing payments.

Put into this perspective, though the current political impasse in the United States is unlikely to produce a US default, it still has macroeconomic effects that will manifest indirectly over the next decade. In the meantime, we can probably expect short-term volatility in global markets leading up to a deal sometime before, or immediately after, the October 17th deadline.