Summary

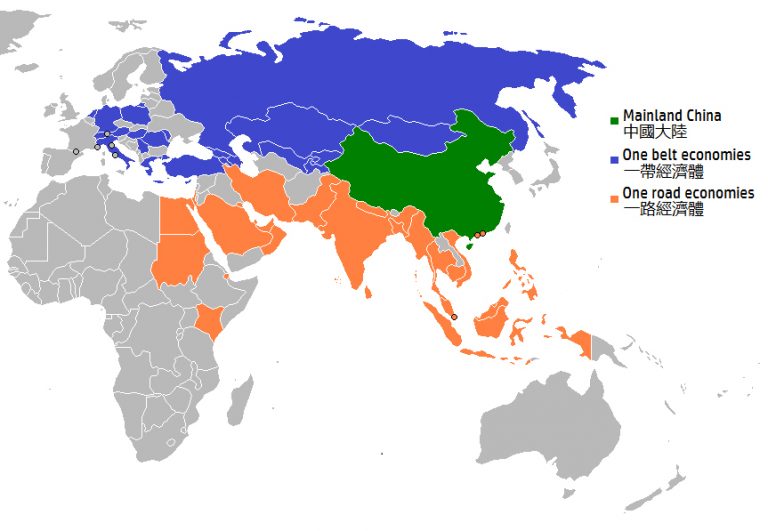

As delegations from Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member states prepare to descend on the Russian city of Yekaterinburg next month, we can expect a spike in media pieces that paint the organization as a nascent ‘anti-NATO’. These media representations overlook a glaring fact: it isn’t in the SCO’s aims or means to become a new Warsaw Pact.

Analysis

The fundamental difference between NATO and the SCO is that the latter lacks any equivalent to NATO’s Article 5- a collective security mechanism stipulating that an attack on one party is an attack on all. The organization can certainly act as a soapbox from which China and Russia can voice congruent security concerns, as was the case in 2005 when the SCO called for a timetable for the U.S. closing Central Asian military bases, there are however many factors that mitigate against a NATO-like deepening of collective security.

On the Chinese side, Beijing has been careful to avoid military alliances, either real or perceived, fearing that they could lead to Western counter-balancing. This is in keeping with the CCP’s ‘peaceful rise’ strategy of maintaining an international environment conducive to Chinese economic expansion. Russia, on the other hand, is reverting back to Soviet-era interpretations of an ‘exclusive zone of influence’ in Central Asia. It’s safe to assume that Chinese influence in their ‘exclusive zone’ is anathema to the Russians.

There was a time when the belligerent expansion of American military and political power had the potential to drive SCO members closer together and into a collective security framework, but it seems that time has passed. If Iraq and Afghanistan proved anything, even before the meltdown on Wall Street, it is that China and Russia need not center their entire defense strategy around a conventional military conflict with Washington, for it is increasingly clear that such a conflict would be economically ruinous for the U.S.

Thus, the SCO should be viewed in its proper context, which is through the lens of Chinese and Russian military, economic, and political security interests.

The organization had an ambiguous inception, boasting an extremely wide and ambitious breadth of proposed cooperation, but paradoxically with no overriding mission statement and thus no strategy for enlargement. The onset of ‘Color Revolutions’ in Central Asia momentarily allowed the SCO to take center stage in combating a shared Sino-Russian concern – encroaching American influence, or worse, a Color Revolution in Chechnya or Tibet.

SCO counter-terrorism cooperation subsequently turned into a coordinated effort to pre-empt and counter any new Color Revolutions in Central Asia. The SCO makes little attempt to hide its collaboration to maintain the political security of member states. A 2007 SCO military exercise in the Russian Urals has been described by defense consultant Gene Germanovich as a “mission to [defeat] a terrorist organization or [reverse] a Color Revolution-style uprising”.

The most ambitious layer of SCO cooperation should be energy security, but even in this regard the organization is still nowhere near becoming something akin to an OPEC. Most bilateral cooperation on energy security still takes place outside of the SCO framework. With no regional strategy for energy cooperation and no hard military collective security guarantee, it seems that the SCO is still far off from becoming what David Wall warned of in 2006, “an OPEC with bombs.”

Iran’s application for full membership was dead before it was even submitted. The SCO isn’t ready to make a move that would, if not only symbolically, send an antagonizing message to Washington. Furthermore, given Sino-Russian mutual suspicions and America’s waning push for a ‘balance of power that favors freedom,’ it is likely that the SCO will never be ready or willing to antagonize the West.

Zachary Fillingham is a contributor to Geopoliticalmonitor.com