As the Russian invasion of Ukraine enters its third year, its implications for the geopolitics of the Arctic continue to unfold.

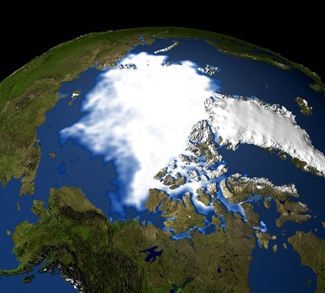

Although a military conflict is unlikely, Russia’s ambitious plans for the Arctic force the region’s other states to reconsider Russian thinking about how to manage potential points of tension. The Arctic Ocean’s continental shelves are one such issue.

At a December public forum in St. Petersburg, Admiral Nikolay Yevmenov, head of the Russian navy, spoke of a “full-scale development beyond the 200-mile limit” of the Russian Exclusive Economic Zone in the Arctic Ocean. What I am translating as “development” here is the Russian word освоение, a word that bears multiple translations, extending from development to mastery to expansion, often with an economic angle. Elsewhere, it is translated as “take-over” or “expansion.” The context in which he spoke it was in relation to the Arctic as a “strategic resource base” of economic development.

In his remarks, Yevmenov closely ties that economic development to the defense of sovereignty and territorial integrity in relation to that resource base, displaying how closely national security, defense and economics are intertwined in Russian economic thinking about the Arctic.

His words were fully in line with the body of strategic thinking that the Russian Federation under President Vladimir Putin has established since 2020. What we find in them does not sit comfortably with the concept of an “A5” of Arctic Ocean littoral states working together to settle jurisdictional questions diplomatically, a concept captured in the 2008 Ilulisat Declaration signed by Canada, the Kingdom of Denmark (for Greenland), Norway, Russia and the United States.

A careful unpacking of Russia’s evolving approach to international law and relations in the Arctic is in order.

First, we should take a step back to look at what is at stake. Demarcating the jurisdictional map of the far northern continental shelf has so far been largely a matter of science, in accordance with requirements the United Nation’s Convention on the Law of the Sea. Briefly put, its Article 76 permits a country to extend past its 200-mile exclusive economic zone to the margins of the continental shelf should it be demonstrated its physical characteristics are continuous. That demarcation comes with rights to exploit resources in that expanded zone.

Canada, Denmark and Russia have all submitted the data underlying their respective claims to the UN’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, which rules on the integrity of the science. (The United States, not a signatory to the Law of the Sea, released its claim in fall 2023.) The commission ruled in 2023 that most of Russia’s submission was valid. Canada’s and Denmark’s claims are only likely to be pronounced upon later this decade or early next. As of now, Canada, Denmark and Russia claim some of the same places in the central Arctic Ocean, concentrated along the Lomonosov Ridge.

Once the commission has ruled, a situation may emerge where all three have empirically justified claims to the same part of the shelf. If so, the final jurisdictional boundaries are agreed upon bilaterally. Canada-Denmark negotiations may not be easy, but however cool-minded they are, they will also be more or less amicable, and strictly at the negotiating table. A precedent for that is the settling of boundary disputes on Hans/Tartupaluk Island and in the Labrador Sea they concluded in 2022.

So, what about Russia? There is good reason to think that Russia will be less than an amicable negotiator and not leave it to the diplomats alone.

Here it is important to look at what the Russian leadership is saying on the matter. Useful resources are its main strategic documents, released over the last four years. The 2023 Foreign Policy Concept, the 2023 amendments to the 2020 Arctic Strategy, the 2022 Maritime Doctrine and the 2021 National Security Strategy reveal that Russia indeed thinks that it has a lot at stake. Canada, Denmark and the United States should take these seriously and prepare accordingly.

To start, these documents make clear that the Arctic Ocean and its continental shelves are an integral part of Russia’s geopolitics and prosperity. The Russian position is committed to exercising an extended jurisdiction on the Arctic Ocean’s continental shelf. Significantly, the National Security Strategy identifies the military’s defense of the continental shelf as a priority, a “goal of state security,” which dovetails with the document’s emphasis on resource exploitation rights as a function of national security and the general priority of the Arctic region in this regard.

The Maritime Doctrine lists the Arctic as the top priority of maritime strategy and is outspoken on Russian interests beyond its exclusive economic zone to the continental shelf and the delimitation of maritime boundaries under international law. The Foreign Policy Concept says that Russia will “step up” (Russian: активизации) the delineating of these borders in a region it identifies as the second most important after the countries of central Asia and eastern Europe, and what it calls the “near abroad.”

These statements fit into a process of geopolitical transformation Russia is trying to undertake to turn into a coastal Eurasian power, defined as much by its northern maritime edge as its terrestrial land mass. While the Arctic has long been touted as central to Russian identity, global warming is opening sea lanes that also conveniently enable Russia’s pivot to Asia, accelerated by the precarious relations with Europe.

This vision of Arctic coastal Russia is closely tied to its prosperity agenda. The region had already been an important part of economic planning. Now it is coming to be seen as the linchpin of future economic development. The Maritime Doctrine describes the Arctic Ocean as the only “vital” ocean to national interests, with its socio-economic development a “decisive condition” for future prosperity. Seabed resources on the continental shelf, it claims, are “predetermined” to be essential to alleviating depleted terrestrial deposits (itself a questionable claim).

Into this mix the strategies assess a sharply competitive, sometimes violent international context, including in the Arctic. The strategic documents describe the other Arctic countries as exhibiting varying degrees of hostility to Russia. The Foreign Policy Concept (Section 50.2, for instance), accuses the other Arctic countries of “militarizing” the region — conveniently ignoring Russia’s own steady modernization of its armed forces in its north.

Russia then goes on to state it will “counteract unfriendly states’ … militarization of the region.” The United States and its allies are pursuing an explicit “containment” strategy and trying to limit its access to the oceanic resources, according to the Maritime Doctrine; it goes on to say the Arctic is a place of “strategic competition.” According to the National Security Strategy, Russia’s Arctic development is being “obstructed” (a reference to sanctions on oil and gas projects). The disparaging epithet of “Anglo-Saxon” is hurled in Canada’s general direction in the Foreign Policy Concept as one of the United States’ henchmen.

The updated Russian Arctic Strategy introduces ambiguity into this overall depiction. It has retained an earlier description of the other Arctic states as “challenges” (Russian: вызовы) and did not elevate them to threats (Russian: угрозы). While it did deprioritize the relations with the other Arctic states from the 2020 document and replace them with bilateral, case-by-case relations with any states, the retention of the “challenge” language is almost certainly not an oversight and optimistically might be seen to represent something of an underlying offer to the Arctic community in the case of improved relations, against the hyperbolic accusations of militarization and Anglo-Saxonism in the other strategies. (A workable hypothesis here is that Russia’s long-term concerns in the Arctic include managing a potentially overreaching China, for which having Arctic partners would be decidedly beneficial for Moscow.)

So, will Russia leave the resolution of any disputes over the continental shelves purely to international law? In the Foreign Policy Concept, Russia reaffirms the “special responsibility of the Arctic states” regarding the Law of the Sea, with a specific reference to maritime delimitation” and sustainable development. It clearly has not abandoned international law.

But Putin and his regime see international law differently from the other (liberal and democratic) Arctic states. They import into their claims about international law the array of deeply cynical assumptions about how the world works, captured in the Foreign Policy Concept’s acknowledgement of the “power factor” in current international relations; diplomacy, it contends, is of decreasing effectiveness.

Cynicism, though, does not exclude sincerity. For Russia, international law is an instrument. The starting point from any consideration of the question in Copenhagen, Nuuk, Ottawa and Washington must be Russia’s flagrant dismissal of international law by its invasion of Ukraine. Russia is not a country defined by its strict adherence to legality.

Expressing this, the subordination of international law to the national interest is a theme running through the strategic documents. The Foreign Policy Concept declares that delimiting the continental shelf will be done in accordance with international law but “unconditionally” in line with its “national interests” and “sovereign rights;” the amended 2023 Arctic strategy added new language foregrounding national interests.

In addition, doubts about the efficacy of international law pervade these documents. The Arctic Strategy and Maritime Doctrine both speak of a group of unspecified countries, presumably Arctic ones, seeking to revise international agreements along national legislative lines. These statements exhibit the leadership’s tendency to use international law instrumentality and see it as malleable to the interests of the “great powers.” They have culminated recently in talk (unlikely to be fulfilled) in Russia about leaving the Law of the Sea entirely.

In short, international law is generated by centers of global power and smaller countries expressing their interests, and balancing them in accordance with power. What the Kremlin is offering when it talks of international law is a framework for discussing national interests, but justice here is not an equally accessible good, instead something that will be decided by the powerful. This is something for Canada and Denmark, in particular, to be attentive to in Arctic matters.

As a consequence, preparedness should be made for a Russia acting superficially in line with international law but covertly seeking to advance its position. The likelihood that Russia will come to open blows over the Arctic is low, but the main threat is not open aggression.

It is to the asymmetric “grey zone” of deniable “hybrid” tools that we should be looking. The strategic documents fully acknowledge the use of force in international affairs, below and above the threshold of open warfare. Notably, in the Foreign Policy Concept it asserts that Russia is the target of a hybrid warfare campaign conducted by the United States and its allies, and the National Security Strategy and Maritime Doctrine provide additional enabling language for asymmetric responses. Reciprocity is a premise of Russian international conduct. These statements provide a clear justification for its use of so-called hybrid or grey zone coercion to achieve policy ends. If it perceives its negotiating position has deteriorated, Russia will be ready to deploy a range of tools, likely to include deniable, coercive ones, below the threshold of open aggression to strengthen its bargaining position.

The strategic documents make clear that Russia is already trying to shape the negotiation space in the Arctic Ocean. If Russia’s relations with its Arctic neighbors remain on the same fraught footing that they are now — a near certainty with another six years of Putin about to start this spring — then it will agitate for maximalist outcomes in obtaining its “sovereign rights” in the Arctic Ocean.

Russian claims are unlikely to extend past what they have stated they want. That does not mean that the coercive “grey zone” will not be an active front in maneuvering for a Russia-optimal settlement or that Canadian and Danish or (by extension) U.S. interests are not at risk.

These three countries need to think about this and start to act now. Acquiring the capabilities that will keep Russia honest at the negotiating table, like icebreakers, submarines, subsea sensors and patrol aircraft, and the infrastructure to support them, takes years. Negotiations in a decades-long time frame will be advanced by establishing a situational awareness that needs to start being built today.

The timelines are long, and we can hope for a different Russia in the next decade or two. But hope, as is often quipped, is not a policy. Canadian, Danish, Greenlandic and U.S. leaders may well face in a decade’s time in the Arctic the same aggressive, uncooperative, and bad faith Russia that we face today in Ukraine. Ensuring we are prepared for hardball hybrid behavior from Russia in the Arctic is a matter for today, so we can be ready tomorrow.

Alexander Dalziel is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute in Ottawa. He has over 20 years of experience in Canada’s national security community. Previously, he held positions with the Privy Council Office, Canada School of Public Service, Department of National Defence and Canada Border Services Agency.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.