As 2025 begins, the end of last year saw two significant results in Georgia and Moldova, demonstrating both the strengths and limitations of Russian interference operations. Both former Soviet Republics are high up on Vladimir Putin’s priority list, so much so that following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the pair, alongside Bosnia and Herzegovina, were identified as ‘partners at risk’ by the NATO alliance. Expectedly, the Kremlin’s obsession with the two countries was on full display with allegations of interference rife in both elections.

Despite the Kremlin’s efforts, the pro-Russian party was only victorious in Georgia, with Georgian Dream securing a parliamentary majority. In Moldova, on the other hand, the pro-EU candidate, and incumbent, Maia Sandu won re-election as president. Limited success notwithstanding, both elections provide an example of the methodology employed by Russia to interfere with democratic elections, as well as providing ominous warnings of Europe’s future should Ukraine be defeated.

Russia’s pleasure was on full display following Georgian Dream’s victory on 26 October, as the head of the Russian state-controlled broadcaster RT, Margarita Simonyan, triumphantly declared that ‘Georgians have won.’ Despite having held power since 2012, Georgian Dream was not widely projected to win; protests against the party had been strong throughout 2024, and turnout on election day was high. Change was expected. However, existential arguments about saving Georgian democracy did not appear to resonate when pitted against Georgian Dream’s assertions that the opposition would take the country to war with Russia.

The election itself was marred with irregularities and accusations of foreign interference. The OSCE were quick to denounce the elections for their irregularities, citing evidence of ‘intimidation, coercion, and pressure on voters. Other transgressions included vote-buying and instances of one person voting multiple times. A member of the European Parliament even caught instances of voter intimidation and ballot stuffing on video. Other issues included double-voting, which could only have been facilitated by complicit election officials.

It is difficult to imagine that the Kremlin was not involved in influencing this election. This was an accusation leveled by Georgia’s President Salome Zourabichvili, who is not a member of the Georgian Dream party. Zourabichvili argued that the election was proof of the Russian ‘methodology and the support of most probably Russian FSB types’ to influence the result in a favorable manner. Evidence of this comes from the use of propaganda videos that were, according to Zourabichvili, a ‘copy and paste’ from those used in the run up to Putin’s ‘election’ earlier this year. These included videos of destroyed Ukrainian cities, which, contrasted with peaceful Georgian ones, were used to depict Georgia’s future if it moved closer to the West.

Russia’s election interference in Georgia was the result of a long and concerted strategy. Months before the election, Russian state media began suggesting that Georgia would fall victim to another, Ukraine-style, ‘color revolution.’ In doing so, the Russian state pre-empted accusations of their interference, by announcing the U.S.’ preference for one party over another. Once Georgian Dream emerged victorious, the Russians were able to downplay complaints of interference by claiming the U.S. had been doing the same – the only difference was that they were not as successful.

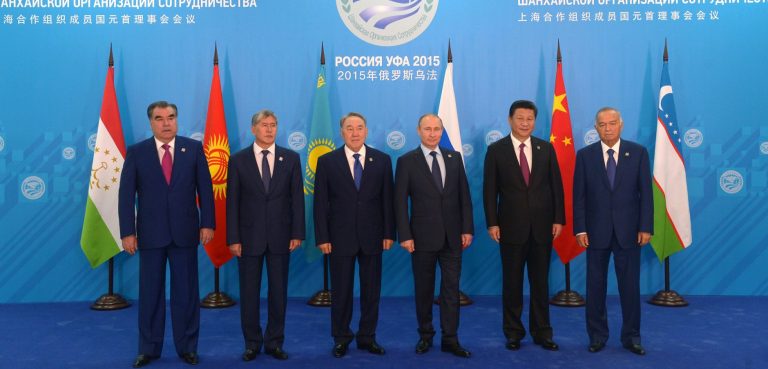

Another element of Russia’s interference playbook is to draw upon its network of autocrats to verify fraudulent elections after they happen. This was, once again, on show in Georgia. Following the election, the U.S., the EU, and a range of multilaterals voiced their concerns with the electoral process; however, one EU member did not tow this line. Not only did Hungary’s Viktor Orban praise the elections as ‘free and democratic,’ he also traveled to Tbilisi, alongside his foreign minister, to add further EU legitimacy to the result. In doing so, Orban helped Putin to spread doubts about Western claims that the results had been tampered with.

The case of Georgia also demonstrates Russia’s methodology for blurring the lines and polarizing the debate after successful election interference. With accusations building following the election results, former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev took to social media to label Zourabichvili a Western ‘puppet.’ Elsewhere, Russian state media alleged that Ukrainian snipers had been deployed to ferment protest, whilst a spokesperson for the Russian Foreign Ministry accused the U.S. of neo-colonialism. Such comments are successful in diminishing Western claims of election interference by passing the blame back to the West and the U.S. in particular. For the Kremlin, the election becoming contested in both directions helps spread uncertainty and, paradoxically, adds an element of legitimacy to the victorious party, who, rather than be seen as having ‘stolen’ an election, are simply viewed as having engaged in similar tactics to the opposition.

Much of the same tactics were on display in Moldova, where the presidential election coincided with a referendum on EU accession. Held on the same day as the first round of the Presidential vote, the EU referendum was decided by just 10,000 votes in favor of moving towards accession. The presidential race, on the other hand, was not as close, with the pro-EU candidate Maia Sandu defeating the more Russia aligned option by a wider margin. Just as in Georgia, fears were stoked of a war with Russia, should the pro-EU candidate win.

Many similar accusations were made against Russia following the Moldovan election as they were following Georgia’s vote. On top of running disinformation campaigns, the Kremlin also engaged in cyber-attacks and similar vote buying strategies to those observed in Georgia. Aided by Russia, voters of the Russian leaning Alexandr Stoianoglo were flown and bused into polling stations, according to Moldovan government officials, whilst bomb threats were called in to dissuade diaspora voters from voting in Germany and the UK. Ultimately however, such attempts proved unsuccessful, but it is unlikely to be the last time that Russia will meddle in European elections. Far from dissuaded by defeat in Moldova, Putin will have been emboldened by victory in Georgia, and with news of Russian interference in Romanian elections causing a political crisis, it seems the Kremlin has already set its sights on a new target. This is a trend that is certain to continue as the new year progresses.

Marcus Andreopoulos is a Senior Research Fellow at the international policy assessment group, the Asia-Pacific Foundation, and a Subject Matter Expert with the Global Threats Advisory Group at NATO’s Defence Education Enhancement Programme. Marcus is currently pursuing a PhD in international history at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.