Western firms looking to build greater resilience into their supply chains in Asia in the wake of the pandemic could face reputational nightmares unless they undertake thorough risk assessments when looking to diversify their sources of products and raw materials in the region.

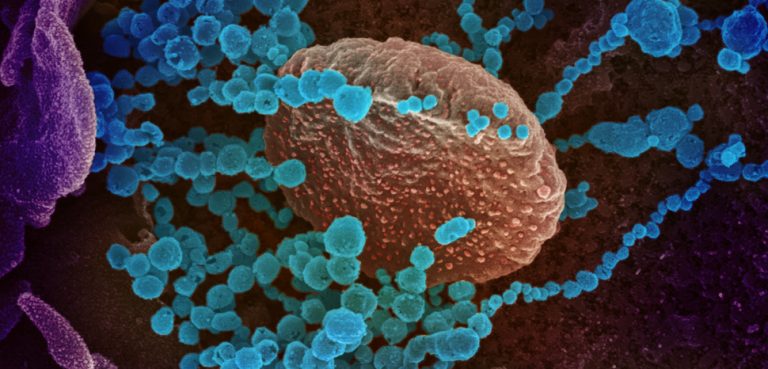

As Covid restrictions ease and some degree of business normality returns, companies sourcing from Asia have been reviewing their supply chains to ensure that they do not face the levels of disruption encountered at the height of the health crisis, when production and logistical hold-ups caused acute shortages of commodities and goods, most notably personal protection equipment.

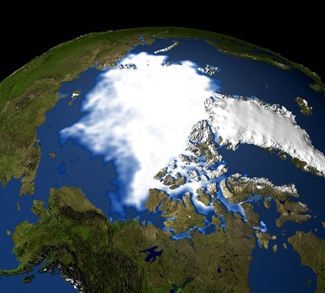

The pandemic sparked a debate about over-reliance on major Asian manufacturing hubs, in particular China. Prior to the pandemic, trade tensions with the US prompted firms to relocate some of their production elsewhere in Asia, and Covid looks like it will expedite the process, even leading to the reshoring of at least some supply.

However, the high costs of bringing production closer to home could militate against such a radical shift in supply in the near term. More evident, for now at least, is a focus on lessening supply dependencies in Asia, essentially a switch over to alternative sources across the region – countries eager to attract Western business to help reboot their economies following the Covid downturn.

Indeed, last month, the governments of Australia, Japan, and India launched the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative in the region, which is seen as a bid to curb reliance on China. Tokyo has already offered Japanese companies subsidies to do so. The US too is looking to address supply chain dependencies for some products, by sourcing those it cannot produce domestically from Asian and Latin American countries.

Yet while diversification is sensible, companies must be careful not to base their choice of suppliers on cost and logistics alone. In the post-Covid era, they should be even more alert to the integrity and accountability of both their partners and the local and national authorities.

As we emerge from the pandemic, scrutiny of supply source is assuming greater and greater importance because investors and consumers are increasingly holding companies to the highest environmental, societal and governance (ESG) standards. Failure to meet these expectations risks exposing businesses to reputational damage and potentially serious financial loss.

In the US, the bottom line consequences are becoming more severe as the customs authorities step up sanctions against imports suspected of links to forced labour in China’s Xinjiang province, in response to the repression of Uighurs and other Muslim groups. From January this year, Washington went further, banning cotton and tomato products from the region. In Britain, meanwhile, companies may face fines if they fail to demonstrate that their supply chains are free of forced labour.

For many businesses, the Xinjiang crisis propelled the perils of sourcing from countries with poor human rights records to the top of corporate agenda, causing some fashion brands to stop sourcing from the province after the scale of persecution was revealed. Even for those confident their supplies are not tainted by abuses, the independent verification required to substantiate the latter may be difficult to achieve because of uncooperative local authorities.

The international outcry over Xinjiang serves as a warning to senior executives seeking to diversify their supply chains in order to mitigate future Covid-like disruption. The message is clear: unless you conduct robust due diligence of suppliers in tandem with political risk assessments of local and national authorities, there is a distinct possibility that you will face a reputational crisis further down the line.

While Asia remains a competitive manufacturing base, international pressure groups are strongly critical of the environmental and human rights records of some countries in the region. In the past, market entry inquiries have tended to center on the integrity of potential suppliers and their ability to fulfill sourcing requirements, but the growing concerns of shareholders and consumers over ESG issues means that the scope needs to be widened.

While it is not always possible to anticipate controversial policies at a local or national level, especially in authoritarian states, robust risk analysis should identify red flags.

The measures companies take to try to establish that their supply lines are free of abuses are important because they demonstrate they are serious about ESG concerns – and these measures have to be communicated clearly to investor and consumer audiences so there are no questions about their commitment.

In the post-pandemic era, companies must guard against future supply chain disruption, but in diversifying their sources they need to pay just as much attention to the attendant risks and their reputational impact.

Farzana Baduel is the founder and CEO of Curzon PR, a global strategy and communications consultancy. She is also a resident public relations expert at Oxford University’s entrepreneurship centre Oxford Foundry, and a former Vice-Chair of Business Relations for the Conservative Party.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com