The post From Ukraine to Myanmar, Drone Warfare Marks a Paradigm Shift appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The strikes from both sides highlight a now indisputable fact: drone warfare is playing a determining role in the Ukraine war.

Armed drones, or Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), are pilotless aircraft used to locate, monitor, and strike targets, including individuals and equipment. Since the September 11 attacks, the United States has significantly expanded its use of UAVs for global counterterrorism missions. Drones have key advantages over manned weapons. They can stay airborne for over 14 hours, compared to under four hours for manned aircraft like the F-16, allowing for continuous surveillance without risking pilot safety. Additionally, drones offer near-instant responsiveness, with missiles striking targets within seconds, unlike slower manned systems, such as the 1998 cruise missile strike on Osama bin Laden, which relied on hours-old intelligence.

There is much discussion in the US defense establishment regarding the use of drones, drone policy and how they should be incorporated into military strategy. According to the Marine Corps University, in order to calculate the effectiveness of a drone strike, several factors must be considered, including Tactical Military Effectiveness (TME), Operational Military Effectiveness (OME), and Strategic Military Effectiveness (SME). TME assesses how well the drone strike achieves its immediate objective, such as neutralizing a specific target. OME evaluates the broader impact on military operations, such as troop movements or operational coordination. Lastly, SME considers the long-term consequences of drone warfare, including the effects of drone strikes on enemy leadership, public opinion, and international relations. All three factors are critical in ensuring that drone strikes align with both short-term and long-term military objectives.

Drones are being deployed in large numbers in the Ukraine war, having already played a major role in the battles between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces in Nagorno-Karabakh. They are also becoming an increasingly key platform in the Myanmar civil war and conflicts across the Middle East. Advanced militaries, including the Pentagon, are closely monitoring these theaters to refine their own drone strategies. For example, recently the U.S. released a ‘drone hellscape strategy’ for the defense of Taiwan, while China has been conducting simulations of a drone-only attack on the island. Yet even the world’s most advanced militaries seem to lack a definitive approach to drone warfare. And, ironically, they continue to learn valuable lessons from underfunded and undertrained rebels in other far-flung global conflicts.

Drone warfare in the Myanmar civil war

The Free Burma Rangers, a frontline aid group in the Myanmar civil war, has been reporting on the increasing incidence of drone warfare in the conflict. On September 6, 2024, a Tatmadaw drone strike resulted in the deaths of four civilians—two men and two women, and one person was also wounded in the attack. Another drone dropped a handmade bomb on a civilian home in Loi Lem Lay Village, Karenni State. During the same incident, a Tatmadaw drone with six propellers experienced mechanical issues while flying over the battlefield and was subsequently captured by the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force (KNDF), a pro-democracy ethnic army. Taken together, these incidents underscore how drone warfare is still in its tactical infancy, with numerous failed deployments, and how payloads and weaponization are often being improvised by soldiers on the ground.

Other rebel armies in the Myanmar civil war, particularly the People’s Defense Forces (PDF), have developed their own drone units. For instance, a PDF unit reportedly carried out 125 drone strikes during the Battle of Loikaw in Kayah State. Another unit claims responsibility for around 80 drone strikes last year, resulting in the deaths of 80 to 100 junta troops. These forces are either manufacturing their own drones or repurposing civilian models by adding deployable explosives. The drones are inexpensive, widely available, and highly effective. Even the junta, supported by China and Russia, has adopted similar tactics by attaching mortar shells to their drones, while ethnic armies often use homemade explosives based on mortar shells captured from the Tatmadaw. These devices can range from 40 to 60mm, carry up to 2.5 kg of explosives and shrapnel, and are capable of killing or injuring anyone within a 100-meter radius in open terrain.

FPV drones a game-changer in the Ukraine war

In addition to homemade and modified drones, first-person view (FPV) drones can cost around $500 USD each, while reconnaissance drones equipped with advanced cameras can run into the thousands. Ukraine is deploying these drones at a rate of 100,000 per month, with plans to produce one million FPV drones in 2024. For a sense of just how important drones have become in the Ukraine war, consider the fact that this figure far exceeds the number of artillery shells supplied by the entire European Union over the past year.

FPV drones, launched from improvised platforms, can fly between 5 and 20 kilometers depending on their size, battery, and payload. Controlled by a soldier using a headset for a first-person view, with another providing guidance via maps on a tablet, these drones are often used to target vulnerable points such as tank hatches or engines. Their real-time video feed, transmitted through goggles or a headset similar to VR gaming, gives the operator precise control, especially in complex environments like urban warfare or dense terrain. FPV drones are effective for reconnaissance, targeted strikes, and even suicide missions, where they carry explosives and fly directly into a target. Unlike planes or helicopters, they are not hindered by anti-aircraft systems near the front lines. In fact, a $500 FPV drone can target the open hatch of a Russian tank worth millions of dollars, demonstrating their cost-effectiveness in modern warfare.

The rise of counter-drone and jamming technologies

As drone warfare becomes increasingly common on the battlefield, a need arises for effective drone jamming technologies. While Russian, Ukrainian, and other armies have access to jammers, ethnic armies in Myanmar lack them almost entirely. Jammers start at $2,400, but many cheap, commercially available models are essentially useless due to significant design flaws. Some have fixed antennae that point upward, despite attacks coming from the side, and many generate excessive heat without proper cooling. This raises concerns about their effectiveness in harsh environments, such as the deserts of the Middle East or the humid jungles of Myanmar.

Moreover, electronic jamming devices work on specific frequencies and drone pilots are adapting by switching to less commonly used ones. To counter this, new technologies like pocket-sized “tenchies” and backpack electronic warfare (EW) systems have emerged, jamming signals across a broader 720-1,050 MHz range, making them more effective against Russian drones. Despite Ukraine’s deployment of these newer jammers, Russia’s use of hunter-killer drone systems like the Orlan-10 for spotting and the Lancet for strikes, along with missile-equipped Orion drones, continue to challenge Ukraine’s drone defenses.

In response, Ukraine has created the Unmanned Systems Force (USF), a military branch dedicated to drone warfare. Additionally, semi-autonomous drones using AI are being developed to bypass jamming altogether. We remain in the nascent stages of drone warfare, where evolution is playing out in real time via innovations on the battlefield. In this sense, US defense spending in Ukraine is serving as an investment in research and development for the drone wars of tomorrow.

The post From Ukraine to Myanmar, Drone Warfare Marks a Paradigm Shift appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Cloud Seeding and the Water Wars of Tomorrow appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The number of people exposed to extreme heat is growing exponentially due to climate change in all world regions. Heat-related mortality for people over 65 years of age increased by approximately 85% during 2000–2004 and 2017–2021.

From 2000–2019, studies show about 489,000 heat-related deaths occurred each year, with 45% of these in Asia and 36% in Europe. In Europe alone in the summer of 2022, an estimated 61,672 heat-related excess deaths occurred. High-intensity heat wave events can bring high acute mortality; in 2003, 70,000 people in Europe died as a result of the June–August event. In 2010, 56,000 excess deaths occurred during a 44–day heat wave in Russia.

Birds are falling out of the sky due to the heat. Reptiles come out seeking shade. Mammals and other wild animals are affected by a severe water shortage. Yet all of this less and less transforms into fresh news nowadays.

But with drought, one day comes food scarcity. Not only for the animals. And it will become a piece of news all the same.

Can humans do something with an immediate effect to prevent at least the food deficit?

Well, they already do it with cloud seeding.

A Brief History of Cloud Seeding

Some states manipulate clouds using a technique called ‘cloud seeding.’ The first cloud seeding techniques date back to the 1940s and involve making clouds merge and grow. This method has evolved into coalescing the particles inside clouds, which fall on the earth drawing down with them other particles encountered on the way, thus making rain or snow. To achieve this, substances had to be artificially introduced into the cloud, most often silver iodide, but various other techniques still exist. Some states also desalinate ocean or seawater, but it is a more expensive approach.

Cloud seeding before being elevated to a geo-engineering technique to combat climate change has gone through a reputation marring. The United States used the technique in the Vietnam War to slow the advance of opposing troops by causing flooding. In 1976, in response to the same use, the United Nations banned environmental modification techniques for military purposes with the ENMOD Convention. From that date onwards, it was forbidden to rain down clouds for ‘hostile’ purposes. However, the hostile nature of manipulation is sometimes difficult to demonstrate; in 1986, the USSR was said to have seeded clouds following the Chernobyl accident to make it rain over Belarus and thus protect Moscow from radioactive rain.

Later came the incidents of ‘stolen clouds.’ In 2011, Iran accused Europe that it had stolen its clouds and afterward in 2018, the story was repeated by an Iranian army general who blamed Israel. The latter case was more dramatic and approached a conflict situation because, in 2018, there was a severe drought in the country and the local farmers were protesting vehemently. Luckily, the head of the Iranian meteorology office intervened by denying the possibility of stolen clouds, which likely helped defuse the conflict. Nevertheless, Iran once again accused Turkey that it also was appropriating its clouds during a recent winter, as the mountain peaks on the Turkish side of their mutual border were snowy while the Iranian peaks on the opposite side were bare, allowing Turkey to attract more tourists.

Today, a country can do whatever it wants with the clouds that cross its airspace, and in many countries, research programs and experiments are multiplying. China has invested colossal sums of money into these techniques, to influence the weather during the Beijing Olympics in 2008, for example, or to combat drought. In 2020, it announced its intention to deploy its cloud seeding program, which until then had been tested on a very targeted basis, over half of its territory by 2025, with the aim of avoiding the droughts and hailstorms that can affect its agricultural production. The Gulf States are also applying seeding techniques using electric discharges in clouds. In France, an association called ANELFA is developing research in this field, with the aim of combating the hail that damages vineyards.

Not Without Its Controversies

In a podcast recorded for France Culture, the writer Mathieu Simonet and the climatologist Olivier Boucher point out that, for the time being, the effectiveness of cloud manipulating techniques remains highly controversial. For one, it is extremely difficult to know whether rain from a seeded cloud would not have existed without seeding.

The techniques raise two important questions for the future. The first concerns the ownership of water resources. While it may seem a trivial subject today, as water resources become scarce over time, there might be a risk of water conflict between neighboring countries over which ‘owns’ the rain. Indeed, if a country decides to ‘make it rain’ on its territory, it may be ‘stealing’ rain that would have fallen later in a neighboring country.

The second question concerns the environmental and health impacts of the substances being used to seed clouds. In large quantities, silver iodide is dangerous for biodiversity, particularly in aquatic environments. An English study carried out by the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology in the early 2000s revealed that silver iodide, below a certain concentration, is not toxic for the environment, but the substance is described as “extremely insoluble.” The risk is therefore that it accumulates and can be harmful over the long term. This obviously can make things more urgent than a creeping food deficit.

Today there are about 50 states which manipulate clouds to ensure ‘ordered’ rain. China has invested $1 billion only for five years in processing clouds. Experiments with cloud seeding are regularly made in the United States, Canada, Gulf countries, France, and Israel, just to name a few.

One proposed method to mitigate global warming with immediate effect is the making of something as a protective coat around the Earth. However, there are opinions that if it were to happen one day, a side effect of it would be nothing less than the disappearance of the blue sky. Here poetry and politics converge. But is that for a good reason when any hope for a prospective disrupting innovation is primarily precluded?

The Water Wars of Tomorrow

Looking 100 years into the future, technologies related to cloud seeding will be undoubtedly highly advanced and at that point, barring a global regime outlining their rightful use, the richest countries, would be able to invest most heavily and ultimately control the clouds.

Apart from everything else, a fundamental problem remains with cloud seeding. The technique works – to the extent that its effects can actually be set apart from natural processes – when there are clouds. But what about if there are no clouds in the sky? What will be squeezed then to make rain? And what can guarantee that the available clouds will always be able to deliver as much as is necessary for crops? Further, even if a cloud is seeded successfully, it does not mean that the rain or the snow will fall exactly on the spot where it is wanted.

And finally, with regard to the expensive process of desalinization, this establishes economic and political dependencies for countries that have no direct access to oceans and seas. How could cloud seeding thus be applied effectively and equitably in a world of growing politico-economic hostilities and fragmentation?

The post Cloud Seeding and the Water Wars of Tomorrow appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Climate Migration: Preparing for Waves of Global Displacement appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>Climate change is forcing people to flee their homes on an unimaginable scale. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, an estimated 30.7 million people were displaced by natural disasters in 2020 alone. This figure is expected to rise as climate change increases the frequency and intensity of such events. Low-lying coastal areas, small island nations, and regions prone to drought and desertification are particularly vulnerable, with millions of people facing the prospect of permanent relocation.

Climate migration raises some of the most fundamental ethical and legal questions. While climate migrants are not like the conventional refugees who run away from conflict or persecution, they lack proper legal protection at the current moment. The 1951 Refugee Convention does not include environmental factors as a basis for seeking asylum, and thus climate migrants are in a vulnerable legal position. This gap points to the importance of the development of an international legal regime that would cater for the needs of climate displaced populations.

Moreover, climate migration is most prevalent among the global population’s least privileged and responsible for emitting the least greenhouse gases. This situation brings forth some of the most pertinent ethical questions in terms of responsibility and justice. The developed countries that have contributed most to the emissions have to be at the forefront in funding climate change adaptation and offering safe refuge to displaced persons.

International organizations need to take the lead in efforts to address climate-induced migration. The United Nations, for example, in the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration has started considering environmental aspects of migration. But stronger actions are required to guarantee that climate migrants will be protected and assisted properly.

Regional bodies can also play a crucial role. For example, the Pacific Islands Forum has advocated for regional agreements that facilitate the relocation of communities affected by rising sea levels. Such frameworks can serve as models for other regions facing similar challenges.

Climate migration is not something that can be solved by a single strategy; it has to be solved through adaptation and mitigation. Adaptation entails the strengthening of the ability of communities to cope with climate effects, which in effect reduces the number of people who will have to be relocated. This can involve spending on physical capital, information systems, and sound methods of farming. Whereas, mitigation deals with the effects of climate change and seeks to minimize the effects that are likely to be experienced in future. In this regard, there is a need for international cooperation where countries collaborate to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Therefore, by reducing emissions, the international society can prevent the long-term causes of climate migration.

At the heart of any approach to climate migration must be respect for human rights and human dignity. Displaced people and communities should not only be viewed as ‘victims,’ but as agents with important experience and capabilities. Policies should enable them to be productive members of their new societies and facilitate their economic assimilation into society.

Climate migration is an urgent and complex challenge that demands immediate and coordinated action from the international community. As John Stuart Mill’s cautionary words remind us, empowering individuals and nations to address this crisis with creativity and determination is crucial. In navigating this new wave of global displacement, the path to our salvation lies in recognizing our shared humanity and collective responsibility. Will the international community rise to the occasion, or will we allow the climate crisis to dwarf our common potential? The choices we make today will shape the future of millions and define the legacy of our generation.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The post Climate Migration: Preparing for Waves of Global Displacement appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Beyond Borders: Applying Modern Conflict Laws as Framework for Outer Space Governance appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>— Goethe

Space wars are upon us. Present-day ground conflicts rely heavily on the infrastructure rendered operational by recurring space missions over the past sixty years. Nations across the globe are making unprecedented investments in both civilian space exploration and its military applications, increasing exponentially the possibility of conflicts in outer space. The militarization of space continues unencumbered by formal agreements and treaties. Grey zone tactics in outer space that fall below the threshold of open conflict continue uninterrupted by a cluster of nebulous governance mechanisms. Contestation and competition over space assets have entered the national security vernacular. Yet despite the self-evident prominence of the threat of force in space, the corpus of law best equipped to regulate and systematize norms of behavior in this domain remains elusive.

The norms and substantive rules of the modern international law of armed conflict alongside international criminal law might offer the requisite guidance in a current landscape where anarchy of meanings regarding the construal of conflict and use of force predominates. It will be up to the international community to decide whether evolving state practice in outer space can congeal behavior into norms, principles, and laws.

Legal Precedent

The principles of jus ad bellum (right to war) and jus in bello (justice in war) have evolved over centuries in response to the need for ethical guidelines in warfare. Jus ad bellum emerged from theological and philosophical debates in the Middle Ages, defining just causes for war, such as the right to self-defense and the duty to protect the innocent. Jus in bello, on the other hand, began to take shape with the development of chivalry codes in medieval Europe. In 1859, the gruesome human cost of the Battle of Solferino fought between the French, Sardinian, and Austrian forces prompted Henry Dunant to elucidate universal principles aimed at imbuing the theater of war with a semblance of humanity. European nation-states enthusiastically embraced Durant’s proposals, which aimed to provide legal protection for military wounded in the field and establish national societies to prepare for wartime needs. This support led to the gradual formalization of non-negotiable protections for war victims, culminating in the Geneva Conventions. The Geneva Convention of 1864 focused on the welfare of wounded soldiers, obligating states to aid them without discrimination. Subsequent conventions extended protections to shipwrecked personnel at sea and prisoners of war and aimed at safeguarding civilian populations during conflicts. The International Red Cross, established in 1870, was instrumental in alleviating wartime suffering. The Geneva Prisoners of War Convention of 1949 outlined the rights and treatment of captured soldiers, while the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War aimed to safeguard civilians from the horrors of conflict. The International Red Cross, established in 1870, played a pivotal role in mitigating suffering during times of war.

The proliferation of conflicts, especially non-international ones, post-World War II prompted the creation of Two Additional Protocols in 1977. These protocols, Protocol I for international conflicts and Protocol II for non-international ones, enhanced protections for victims and imposed limits on wartime conduct. They extended safeguards to civilian medical and religious personnel, cultural heritage sites, and medical facilities.

The Geneva Law, which focuses on protecting individuals from suffering, complements the Hague Law, which delineates permissible conduct for military forces during armed conflicts. Together, they form essential pillars of international humanitarian law. The primary objective of the body of rules known as the Law of the Hague is to prohibit certain means and methods of combat that are deemed excessive. It encompasses various treaties and protocols aimed at regulating warfare and minimizing unnecessary suffering. Beginning with the Declaration of Paris in 1856, which addressed privateering and the conduct of enemy ships at sea, and extending to the Declaration of St. Petersburg in 1869, which outlined the legitimate aims of warfare and set limits on its methods, the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 further solidified these principles. They explicitly banned the use of poisoned weapons and projectiles causing unnecessary suffering and established guidelines for belligerents in occupied territories. Article 22 of the Hague Convention IV underscores that the means of injuring the enemy are not without limits, applicable across all theaters of war.

Subsequent treaties and protocols aimed to curtail or prohibit weapons causing disproportionate suffering, such as poisonous gas, chemical, and biological weapons, and indiscriminate weapons like landmines and explosive remnants of war. Additionally, the Hague Cultural Property Convention of 1954 seeks to safeguard cultural heritage during armed conflict. The 1998 Rome Statute on the International Criminal Court complements these efforts by expanding upon the provisions of the law of armed conflict and addressing international crimes, including war crimes. It ensures adherence to international humanitarian law and establishes guidelines for the scope and methods of war and the use of force under public international law.

Fundamentally, the law of armed conflict embodies a set of clear and practical principles aimed at balancing humanity with military necessity. These principles include distinction between combatants and civilians, proportionality in the use of force, recognition of military necessity, limitation on means and methods of warfare, humanity in the treatment of protected persons, and the importance of good faith and reciprocity between opposing forces.

The non-governmental effort to clarify and articulate the application of laws of armed conflicts or international humanitarian law to outer space is already underway. The Woomera Manual on the International Law of Military Space Operations – an international research project spearheaded by the Universities of Adelaide, Exeter, Nebraska, and New South Wales – seeks to clarify existing laws applicable to military activities in space, particularly during periods of heightened tension or conflict when state and non-state actors might consider using force. Any resort to force by states, including in outer space, is governed by the prohibition of the threat or use of force under the UN Charter.

LOAC and Outer Space

Considering the comprehensive framework established by modern laws of armed conflict, the field of outer space law stands to benefit significantly from its principles and provisions. Just as these laws have evolved to regulate interstate warfare on planet Earth, they could serve as a foundational framework for governing activities in outer space. By adopting and adapting the principles of distinction, proportionality, limitation, and humanity, among others, outer space law can effectively address the unique challenges and complexities of space exploration, its use, and potential conflict.

The principles of distinction, which require a clear differentiation between military and civilian objects, and proportionality, which mandates that the use of force must be proportionate to the military objective, are particularly relevant in the context of outer space activities. As space becomes increasingly crowded with dual-use technologies, commercial satellites, spacecraft, and other assets, it is essential to establish guidelines to prevent unintentional harm to civilian infrastructure and personnel in space and on Earth.

Moreover, the concept of limitation, which dictates that the means and methods of warfare are not unlimited, can help prevent the escalation of conflicts in space by imposing restrictions on the use of certain weapons or tactics that could cause indiscriminate harm or result in long-term consequences for space exploration and utilization. Given a growing number of distinct weapons systems in orbit – from missile defense systems with kinetic anti-satellite capabilities, electronic warfare counter-space capabilities, and directed energy weapons to GPS jammers, space situational awareness, surveillance, and intelligence gathering capabilities – legal clarity rather than strategic ambiguity are crucial for ensuring the responsible and peaceful use of outer space.

Additionally, the principle of humanity underscores the importance of treating all individuals with dignity and respect, including astronauts, cosmonauts, and civilians who may be affected by conflicts in space. By upholding this principle, outer space law can ensure that human rights are protected and preserved, particularly in the profoundly challenging environment of outer space. Moreover, with civilians on the ground increasingly tethered to space technologies for communication, navigation, banking, leisure, and other essential services, the protection of their rights becomes a fundamental imperative.

The modern laws of armed conflict (LOAC) offer a valuable blueprint for developing a robust legal framework for governing activities in outer space. By integrating complementary principles of LOAC or international humanitarian law with the UN Charter into outer space law, policymakers can promote the peaceful and responsible use of outer space while mitigating the risks associated with potential conflicts in this increasingly contested domain.

Dr. Joanna Rozpedowski is a non-resident Senior Fellow at the Center for International Policy and Adjunct Professor at George Mason University.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The post Beyond Borders: Applying Modern Conflict Laws as Framework for Outer Space Governance appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Drone Swarms: An Asymmetric Game-Changer? appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

What is a drone swarm?

Drone swarm technology involves coordinating groups of three to thousands of drones to execute missions collectively with minimal human intervention. Compared to single drones, swarms offer enhanced efficiency and resilience, performing multiple tasks simultaneously and remaining on mission when individual drones fail. A swarm can be controlled in various ways, including preprogrammed missions with specific flight paths, centralized control from a ground station or a single control drone, and distributed control where drones communicate and collaborate using shared information (fully autonomous). More sophisticated control techniques involve swarm intelligence, inspired by the collective behavior of insects and birds, and artificial intelligence to enable drone swarms to adapt to new or unforeseen situations.

The post Drone Swarms: An Asymmetric Game-Changer? appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post What Drives US Opposition to the Law of the Sea Treaty? appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The UNCLOS treaty boasts a membership of 168 countries, along with the European Union. Additionally, 14 United Nations Member States have signed UNCLOS but have yet to ratify it. Notably, only 16 United Nations Member and Observer States have refrained from both signing and ratifying UNCLOS. Among them is the United States of America, which has signed but not ratified the treaty.

The post What Drives US Opposition to the Law of the Sea Treaty? appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems: A Gamechanger Demanding Regulation appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The rise of AI in the military domain is rapidly changing the face of warfare, as AI-enabled weapon systems potentially diminish the meaningful role of human decision-making. As defined by Nils Adler (2023) in an article publish by Al Jazeera English “autonomous weapon systems can identify their targets and decide to launch an attack on their own, without a human directing or controlling the trigger.” There is a global consensus that “cutting-edge AI systems herald strategic advantages, but also risk unforeseen disruptions in global regulatory and norms-based regimes governing armed conflicts.”

Experts and scholars believe that AI-enabled weapon systems will have a major impact on warfare, as the full-autonomy of weapon systems would negate battlefield norms established over the course of centuries. According to the European Research Council (ERC), “militaries around the world currently use more than 130 weapon systems which can autonomously track and engage with their targets.”

Despite advancements in this domain, there is no globally agreed definition on what constitutes a lethal autonomous weapon system; the question of autonomy on the battlefield remains subject to interpretation. The US Department of Defense (DOD) defines LAWS as “weapon systems that once activated, can select and engage targets without further intervention by a human operator.” Such a concept of autonomy in weapon systems is also known as ‘human out of the loop’ or ‘full autonomy.’ In a fully autonomous weapon system, targets are selected by the machine on the basis of input from AI, facial recognition, and big data analytics, without any human crew.

Another category of autonomy in weapon systems is semi-autonomous or ‘human in the loop’ weapon systems. Such weapons are self-guided bombs and missile defence systems that have existed for decades.

The rapid advancement in the use of LAWS has created the need to develop a regulatory framework for the governance of these new weapon systems. Accordingly, various states have agreed to enter into negotiations to regulate and possibly prohibit LAWS. The United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (UN CCW) has made several efforts in this direction by initiating an international dialogue on LAWS since 2014. The Sixth Review Conference of UN CCW in December 2021 was concluded with no positive outcome on the legal mechanism and an agreement on international norms governing the use of LAWS. Despite the stalemate, there was consensus that talks should continue.

In 2016, a Group of Governmental Experts (UN GGE) was also established with the mandate to discuss and regulate LAWS. But the participating countries have yet to make headway on a legal framework to regulate and proscribe the development, deployment, and the use of LAWS.

As the world advances in the use of AI in the military domain, states have moved to take divergent position in the UN CCW on the question of development and use of LAWS. Incidentally, certain countries would only find it in their interest to sit down for arms control measures once they have achieved a certain degree of technological advancement in this domain.

It should be noted that major powers such as the United States, China, Russia, and the European Union (EU) either do not outright prohibit or have sought to maintain ambiguity on the matter of autonomous weapons. A US Congressional Research Service report, updated in February 2024, highlighted that “the United States currently does not have LAWS in its inventory, but the country may be compelled to develop LAWS in the future if its competitors choose to do so.”

China is the only P-5 country in the UN CCW calling for a ban on LAWS, stressing the need for a binding protocol to govern these weapon systems. China at the UN CCW debates has maintained that “the characteristics of LAWS are not in accordance with the principles of international humanitarian law (IHL), as these weapon systems promote the fear of an arms race and the threat of an uncontrollable warfare.”

Russia remains an active participant in discussions at the UN CCW, opposing legally binding instruments prohibiting the development and use of LAWS.

The EU has adopted a position in accordance with IHL which applies to all weapon systems. The EU statement at GGE’s meeting in March 2019 stressed the centrality of human control on the weapon systems. EU maintains that human control over the decision to employ lethal force should always be retained.

World leaders, researchers, and technology leaders have raised concerns that the development and use of LAWS will adversely impact international peace and security. In March 2023, leaders in various high-tech fields signed a letter calling for a halt in the development of emerging technologies for the next six months. The letter warned of the potential dangers to society and humanity as the tech giants race to develop fully autonomous programs.

History reminds us that a virtual monopoly on technological development can never be maintained and upheld for long. In the 1940s, for example, when the United States developed a nuclear bomb under the Manhattan Project, other powers caught up and built their own bomb. However, it took more than two decades for the global community to formalize an agreement to prohibit the proliferation of nuclear weapons, known as the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

The unregulated growth and proliferation of LAWS threatens to unleash a new era of warfare fueled by autonomous platforms, compromising human dignity, civilian protection, and the safety of non-combatants. Henceforth, there is a need for states to find common ground to regulate and formalize an understanding of human control over the use of force. Global values, ethics, and rules of warfare that have guided humanity over the last two thousand years remain imperative for upholding international peace and security.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The post Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems: A Gamechanger Demanding Regulation appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post BRI, PGII, and Global Gateway: Infrastructure Development Goes Global appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>Beijing’s new focus on a smaller, smarter, and greener Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the West’s commitment to infrastructure adhering to ESG standards could, in theory, help turn a new generation of roads, railways, dams and ports into economic assets that effectively mitigate debt, corruption and environment risks.

There is a huge global infrastructure investment gap. Among developing nations, it’s particularly acute, making it hard to tackle the demands and challenges of rapid population growth. Moreover, the funding shortfall limits these countries’ financial prospects at best, deepening poverty and, ultimately, threatening to destabilize them at worst.

Just over ten years ago, Beijing recognized the investment need – and, its critics would argue, the economic and political influence that addressing the need could leverage. China became the developing world’s biggest lender, largely through the BRI, whose membership runs to over 150 countries, more than a dozen of them EU states. But some recipients of loans have struggled to repay. As of October, member countries owed more than $300 billion dollars to the Import-Export Bank of China, according to Chinese officials.

At the same time, the Chinese economy has cooled, leaving less room for foreign expenditure. And, as their own economic circumstances have worsened, there are signs that some Chinese are beginning to question the merits of spending billions abroad. Against this background, investment in the BRI has declined significantly. Long critical of its lack of transparency and debt implications, and concerned over the geopolitical influence it allows China to wield, the West has now sensed an opportunity to roll out rival infrastructure schemes.

Launched with great fanfare in 2013, the BRI was intended to present China as a champion of the developing world, though there was an important domestic economic driver too. The country needed to secure new markets for excess capacity after the global financial crash when Beijing invested heavily to stimulate in its own economy (China now has a substantial trade surplus with BRI members). The BRI has also been seen as a means of promoting Beijing’s authoritarian model of governance and advancing its geostrategic goals, primarily by shifting countries out of America’s sphere of influence.

Under the BRI, Beijing has loaned around one trillion dollars to low- and middle-income economies to develop sectors such as transport, logistics, utilities and energy. As part of the initiative, health and education programs have also been pursued. Infrastructure outcomes have been mixed. Many BRI signatory states have benefited substantially, particularly in Southeast Asia. Yet a sizeable minority of infrastructure projects, reports AidData, have experienced major implementation problems (including corruption, labor violations, and environmental hazards).

While a significant number of BRI countries have fallen into heavy debt, requiring bailouts from China, there is limited evidence to suggest that Beijing is engaged in debt-trap diplomacy, essentially the claim that it looks for economic concessions from countries struggling to repay loans. Indeed, in recent years it has sought to de-risk or future-proof investments, by putting in place “stronger loan repayment and project implementation guardrails,” according to Brad Parks, the executive director of AidData.

At the third Belt and Road Forum in October, China said it would commit more than $100 billion for what looks like a rebranding of the BRI – notably coinciding with an uptick in BRI expenditure last year, the highest since 2018. Beijing seems to have acknowledged that the problems that have dogged the BRI should be addressed if it is to be credible. And the rebrand has not come out of the blue, seemingly building on efforts in previous years to make the BRI more sustainable through a series of green policies and guidelines.

In the new iteration of the BRI, provision will be made for big-ticket and “small yet smart” infrastructure, including green and low-carbon energy projects, with signs of possibly a more cautious financing approach, says China Dialogue. Also there’s a new emphasis on host country agency; an effort to combat the narrative that BRI projects directly benefit China. And to address integrity and compliance issues, companies participating in projects will come under closer scrutiny.

The rebranding of the BRI has emerged as the West attempts to give developing countries alternative options. The European Union’s Global Gateway, launched in 2021, aims to raise up to 300 billion euros of public and private funds for sustainable and high-quality infrastructure projects, which comply with social and environmental standards.

As of October, 89 projects have got under way globally, with 66 billion euros so far committed. The same month, the European Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen was very clear about the purpose of the Global Gateway, insisting it was about “better choices” for developing nations. “For many countries around the world, investment options are not only limited, but they all come with a lot of small print, and sometimes with a very high price,” she said.

In 2022, the US and its G7 allies formally launched the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), which is looking to mobilize 600 billion US dollars of public and private investment for quality, sustainable infrastructure. Its two signature projects are transport corridors, one linking India, the Arabian Gulf, and Europe, the other in Africa connecting Angola, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The PGII, like Global Gateway, makes no bones about its intentions. It says it offers “a positive alternative to models of infrastructure financing and delivery that are often opaque, fail to uphold environmental and social standards, exploit workers, and leave the recipient countries worse off.”

While Western attempts to lower the risks associated with large infrastructure projects is a step in the right direction, doubts remain about the feasibility of these initiatives. Amid the global slowdown, will creditor governments be able to raise the funds needed? And will the schemes attract sufficient private investors if investment-recipient countries are politically and financially unstable, raising ROI uncertainty? Moreover, it might turn out to be hard to identify and then deliver projects that adhere to high ESG standards.

At the same time, questions could also be raised about China’s infrastructure rebrand. Developing nations that have had bad experiences of the BRI may wonder whether there’s any real substance behind the new offering. Not least those that have incurred big debts – once bitten, twice shy. And countries concerned about the BRI pushing them further into China’s sphere of influence might also have second thoughts, especially if there are more attractive Western projects on the table.

While the geopolitical rivals’ schemes have their doubters, it must be said that the West’s recognition of the sustainable infrastructure needs of the developing world and China’s apparent willingness to draw lessons from the past are positive moves. Emerging economies will now have choices, at least. Previously, there would have been few if they turned down Chinese overtures. Moreover, a decade after the launch of the BRI, they will be – or should be – more aware of, and better able to assess, the relative merits and potential pitfalls of big infrastructure projects.

Yigal Chazan is an international affairs journalist, with a special interest and expertise in geoeconomics.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The post BRI, PGII, and Global Gateway: Infrastructure Development Goes Global appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Soy Prices Slip from Post-Pandemic Highs appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

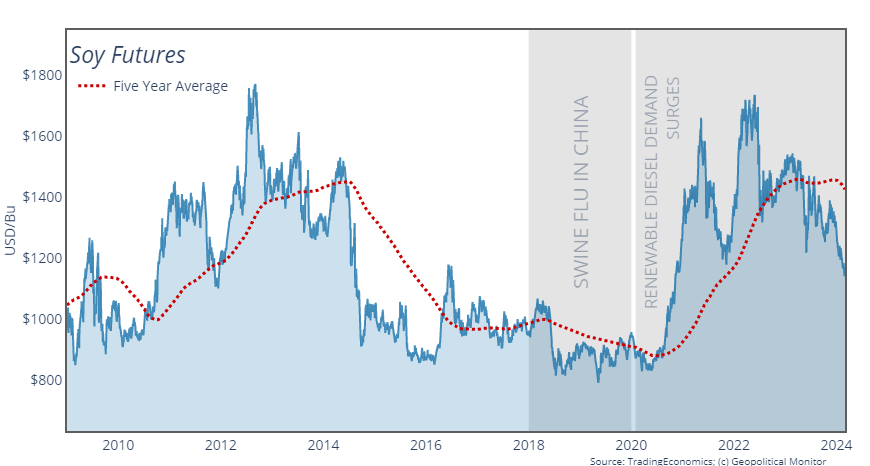

As one of the world’s most traded commodities, soybeans are a critical feature in the global agricultural landscape. Movement in soy futures can influence the stability of different countries: shaping trade policies, impacting diplomatic relations, and determining domestic stability through the movement of key input prices. Countries like the United States, Brazil, and Argentina, which are leading soybean producers, often leverage their production capacity as a significant economic asset, affecting global supply chains and price dynamics. On the other side, major importers like China, whose massive demand for soybeans stems from its vast hog sector, view soybean imports through the geopolitical lens, ascribing the commodity critical importance for food security and agricultural policy. This geopolitical significance was evident during the US-China trade war, as soy was one of the first commodities targeted for sanctions in 2018.

The post Soy Prices Slip from Post-Pandemic Highs appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>