The abrupt ouster of the Assad regime in Syria after five decades of its reign caught governments around the world by surprise. This sudden transition of power and major shift in the geopolitics of the Middle East have implications for many countries. In light of this new normal, we evaluate the implications and potential prospects for Beijing in the political, economic, and security realms.

Türkiye sees the removal of Assad as a chance to normalize relations with Syria through the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) and the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) group. The fall of Assad signifies the loss of one of Putin’s significant Middle East allies, which reportedly led to the dismantling of some military equipment and the withdrawal of military personnel from Syria. The possibility of a Syrian-style revolution in Tehran and the necessity of Iran’s increased commitment to thwarting outside pressures have become major considerations. Losing Assad might also make it harder for Iran to supply Hezbollah, its proxy group in Lebanon. Similar to Türkiye, the United States (US) and Israel have a unique chance to strengthen their power in the country and the Middle East at the expense of Iranian and Russian sway.

The disintegration of the ‘Shi’a crescent’ and the deterioration of the ‘Axis of Resistance’—of which Syria was the sole United Nations (UN) member—along with China’s loss of a ‘strategic partnership,’ has fostered a prevailing view that China is currently facing only regional setbacks. Given China’s cautious and pragmatic approach in the Middle East, as well as Beijing’s diplomatic engagement with the Taliban in recent years, the negative impact of Assad’s overthrow on China may be overstated; however, there are reasons to believe that Beijing will see some opportunities in a post-Assad Middle East. Unfortunately, the situation is not entirely positive.

China loses a ‘strategic partner’ in the Middle East

The fall of Assad possibly marked the end of a ‘strategic partnership’ that Beijing established on September 22, 2023. President Xi Jinping and former President Bashar al-Assad forged the partnership a little over a year ago during a meeting in Hangzhou. Yet, the ‘strategic partnership’ is only a recent development in the long history of relations between the two countries. Syria, along with Egypt, Yemen, Iraq, Morocco, and Sudan, was among the first Arab countries to recognize and establish diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Syria was an early co-sponsor of the resolution to re-establish the PRC’s legitimate seat in the UN.

China’s nationalist government recognized Syria in 1946, and diplomatic relations were established on August 1, 1956—the same year that Sino-Soviet relations began to deteriorate as Khrushchev launched his de-Stalinization program in the Soviet Union and the ‘Great Purge’ of Soviet society. It marked the onset of strained relations and a serious conflict between Moscow and Beijing. Overall, the shifting dynamics of the Cold War era affected China’s relations with the Middle East, but it had no actual aim of becoming involved in the region’s politics. It interacted with the region under the umbrella of ‘Third Worldism’ during the Mao period. Relations with other important regional actors—Palestine, Israel, Türkiye, and the ‘West Camp’ Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries—developed years later and across decades.

Crucially, China’s current involvement in the Middle East reflects some of the same aims, motivations, and actions as during the Cold War, but its position in the region has changed substantially. Beijing’s present-day relationship with the region consists of four facets: domestic/regional security, culture, economy, and politics/diplomacy. China developed its relations with Syria through bilateral and UN financial investment, aid, and diplomatic channels, but it was never as involved in Syria as the US, Russia, and Iran. In this respect, China’s loss from Assad’s departure is limited, largely symbolic, and dispersed over political, economic (finance and markets, energy and resources), and distant or indirect local security and threat perception concerns. Beijing’s projection of China as a great power underpins all of them.

Against the backdrop of Syria’s current volatility, the dynamics on the ground, and China’s historical reluctance to become involved in conflicts, it is likely that Beijing will remain cautious and closely observe the next steps taken by other regional and external actors. All of the economic and security concerns, both present and prospective, are considered within a broader political framework. The expansion of China’s economy is the country’s top goal since it enhances its political and diplomatic influence and its military strength, which in turn boosts its reputation as a great power. That being the case, China will seek out strategies to fortify its ties to key regional markets. For China to meet its basic needs and achieve its lofty global ambitions, such as becoming a great power, oil is the most important commodity.

Economic considerations

Syria’s crude oil production peaked at 582,300 barrels per day (BPD) in 1996. That figure fell rapidly after a gradual decline leading up to the 2011 Arab Spring and ISIS’s activities. By August 2024, its crude oil production was only 95,000 BPD. China imports 47% of its crude oil from the Middle East; however, the regional import landscape varies. More than a quarter of its oil comes from Saudi Arabia, followed by Iraq, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates. Even in 2014, China scarcely relied on Syria as a source of oil. Syria’s exports to China in 2022 totaled merely $2 million USD, with the main commodities being vegetable goods, soaps, soap-related products (e.g., cleansers, candles, etc.), and olive oil.

Beijing never saw these imports as crucial. Syria has never been a leading producer or power; in 2010, it contributed just 0.5% of the world’s total production, which was 0.2% less than all of Eastern Europe and 0.2% higher than Australia and New Zealand’s projected crude oil production between 2022 to 2050, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). Even at peak production, Syria’s oil potential, albeit minor in comparison to other oil-producing giants in the region, was mostly for domestic consumption and low-level exports. Nonetheless, it continues to be a substantial source of revenue for any ruling group; a decade ago, ISIS used it to fund their phenomenally successful terror and militant operations.

Considering the potential impact on China of Assad’s ouster requires an understanding of US policy. However, it is still in its infancy and is exceedingly elementary. In the days immediately following the Assad regime’s collapse, the White House supported Israel’s 480 targeted strikes across Syria. US forces also conducted their own precision airstrikes inside Syria. On Sunday, December 7, President Joe Biden described Assad’s downfall as a ‘historic opportunity’ and a moment of risk.’ The so-called ‘blueprint’ of the Biden administration, which has only five weeks left in office, appears to provide little, if anything, in terms of a post-Assad plan.

Despite the uncertainty surrounding the US role in Syria following Assad’s fall and the lack of clarity within the US government about the potential benefits of these changes, Washington maintains a presence of approximately 900 military personnel in the country. While US Central Command (CENTCOM) continues to launch targeted strikes against ISIS positions and personnel, other factions, including ISIS, have targeted US military installations since Assad’s downfall. The soon-to-be Trump administration has been explicit about its position on Syria. After learning of the events that took place in Syria, the incoming president posted on the same day on his Truth Social network: Syria is a mess, but is not our friend, & THE UNITED STATES SHOULD HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH IT. THIS IS NOT OUR FIGHT. LET IT PLAY OUT. DO NOT GET INVOLVED! [original emphasis].’

Some analysts suggest that Washington will not significantly influence the events in Syria now that Assad has left. Although this assessment is questionable, it could mean that Türkiye would have the most influence on the country. For Türkiye, the biggest priority is rebuilding a stable Syria. In light of the mutual interests of Türkiye and China in fostering closer cooperation after years of stagnation, which includes expanded trade and investment, Ankara’s involvement in the reconstruction of Syria could be advantageous to Beijing.

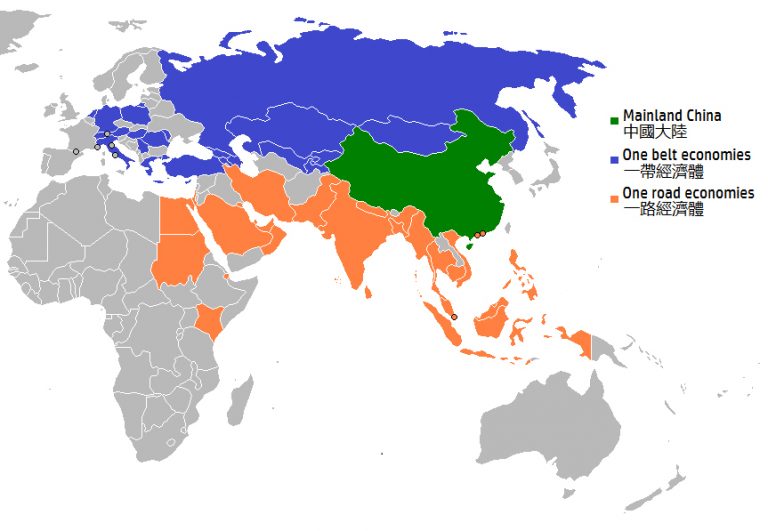

Xi’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is one of the most critical factors in relation to Syria, China, and Türkiye. In 2012, Ankara and Beijing signed a ‘swap agreement’ between the Central Bank of Türkiye and China. The amount of the agreement is 10 billion yuan, or 3 billion Turkish lira, and it was renewed in May 2019. In November 2015, during the G-20 Leaders Summit in Antalya, Ankara and Beijing signed a ‘Memorandum of Understanding on Aligning the Belt and Road Initiative and the Middle Corridor Initiative,’ three years after the agreement. Since then, Türkiye has maintained its backing of the BRI, which includes the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road.’ It continues to be seen as a mutually beneficial, or ‘win-win’, partnership, as it was in the past. The potential extension of the BRI through Syria, which would drastically aid the country’s post-war reconstruction and promote socio-economic development across many sectors of the country, further underscores its relevance.

The prospect of a Belt and Road Initiative via Syria highlights China-Russia relations and the debate between a northern and a southern route. The development of the Southern Silk Road through Syria and Türkiye, which would connect lucrative European markets with China and all those situated along the trade route, could yield tremendous benefits from the perspectives of Syria, Türkiye, and China. Although the idea of the project had once been limited by the threat posed by ISIS during the height of its power and expansion in 2014 and 2015, when it held approximately 30% of Syrian territory, and the devastating civil war, the project now has a greater opportunity to be realized, even in spite of the continued presence of rebel factions in Syria. The Northern Silk Road, which would connect China with Europe through Central Asia and Belarus—close to the Ukraine conflict zone and through its more ideologically postured partner, Russia—and the Southern Silk Route, which would pass through Syria, is likely to become a more serious topic of discussion in the coming months.

For China, the Middle East holds significantly greater economic significance than Russia, and despite the persistent conflict, it represents a more dependable and investment-wise option in the long run. Moreover, although Middle Eastern nations embrace their commerce with China, they occupy a strong position as they supply China with the vital resources necessary for its daily operations and the expansion of the state into the great power that Xi aspires to achieve. The main distinction between Syria and its oil-rich Middle Eastern counterparts lies in Syria’s war-torn economy and shattered infrastructure, which places any new government in a more precarious position with diminished economic leverage.

The potential for access to the Mediterranean is also of strategic importance to China. Conversely, SIG has a greater need for China than vice versa, as any infrastructure investment is essential for its political survival.

Security concerns

A major caveat of the Turkish-Chinese relationship in the context of Syria’s power transition is the Uyghur issue. Earlier this year, in March, Beijing expressed concern about Ankara’s policy of ‘defending the rights of Turkic Uyghurs in the international arena.’ Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu remarked, ‘Why should we become a tool for China’s propaganda?’ while also saying that we want to cooperate, we don’t see this as a political issue. We are categorically not anti-Chinese. We have consistently declared our endorsement of the One-China policy.’

A jihadi group with a strong Uyghur majority, the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) has lately made its anti-China stance and threat of violence against the Chinese government very clear. The TIP, a Sunni Islamist political and paramilitary organization, announced on December 8, that it would be broadening its jihad from Syria to the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR) in western China. This region, also known as East Turkistan or ‘Uyghuristan’, is home to approximately 11 million Uyghurs of the same sect.

In recent days, the organization’s fighters have been involved in the seizure of Damascus and the overthrow of the Assad regime, according to a video they published. ‘We fought in Homs, in Idlib, and we will continue the fight in East Turkestan. Allah has granted us victory here. May He grant us victory in our land as well’, said one of the fighters. According to reports, HTS aired a propaganda video out of Syria in which it urged Muslims to answer the call of jihad, rise up in revolution against the tyrannical Chinese government, and liberate themselves from Chinese control. It appears that the HTS, despite its assertions, has not completely or totally abandoned its militant-extremist character and personality. This development marks a major shift in the terrorism landscape and presents an alarming security concern for Beijing.

After fleeing China in the 1990s, the TIP trained in Syria with the Islamist group HTS. The TIP’s recent declaration of its intention to ‘liberate’ East Turkistan has caused alarm in Beijing. New concerns regarding the security of its westernmost province and the integrity of its western frontier have arisen on account of this latest development, which may put a strain on relations between Türkiye and China and complicate Chinese interests in Syria. Moreover, this latest development may influence the relationship between the Taliban and China, as well as other extremist groups in China’s geographic periphery.

By focusing attention on Beijing’s internal challenges with terrorism, separatism, and potential fragmentation—in this case, the ‘liberation’ of ‘Uyghuristan’ from Chinese ‘occupation’—other states may exploit the growing animosity of these groups toward China, as well as any escalating violence and insurgency, to undermine China’s political reputation.

What’s next?

Power dynamics and the balance of power in the Middle East have clearly started to change. While Türkiye, the US, and Israel face new opportunities, Russia and Iran face growing challenges and anxieties. China is careful in its partnerships with other actors and regions, and although it maintains a ‘good’ relationship with Russia, it is no different. This is reflective of China’s circumspect approach to the Middle East following Assad’s demise. Ahmad al-Sharaa—known under his nom de guerre, Jolani—said that Syria will not be a threat to the world, and he seeks a peaceful neighborhood.

At the moment, the Middle East’s political and security issues are not in equilibrium; the development of this and its broader ramifications will take time. Furthermore, experts disagree on how the recent and unexpected events in Syria, its post-Assad transition, and broader regional implications will affect China both now and in the future. China’s response to quickly changing events should be cautious and methodical, as the full consequences of the Assad regime’s collapse are still being felt. For the time being, China, like in past years, continues to prioritize economic priorities over ideological ideals, retaining its pragmatic approach based on the vision of long-term development and what is best for Beijing’s survival and prosperity.