Summary

US Vice President Mike Pence has announced that the United States will work together with Australia to jointly upgrade the Lombrum naval base on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea (PNG).

The base will be co-developed by the United States, Australia, and Papua New Guinea. Overlooking busy Pacific trade routes on the northern extremity of PNG, Lombrum was a major US naval base during World War II that has since fallen into disrepair. Though details of the upgrades remain scant, Australian Defense Minister Christopher Pyne has confirmed that Australian naval vessels would probably be permanently based at Lombrum once the work is complete.

The move represents a deepening of US-Australia military cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. Taken together with the announcement of lucrative new aid provisions from Japan, Australia, and the United States, a picture emerges of coordinated engagement from the Quad (minus India) in a region that has figured prominently in China’s Belt and Road plan. Beijing has offered billions in financing to island nations in the Pacific, in some cases supplanting Australia as primary donor. There have been rumblings that these loans could one day open the door to a PLA Navy base in the region, with Vanuatu being rumored as a possible landing spot earlier this year.

Impact

Building up the hard power behind FONOPS. In announcing the new agreement, Vice President Mike Pence didn’t mince words on US intentions: “We will work with these two nations to protect sovereignty and maritime rights in the Pacific Islands.” Pence stressed that the US was committed to an open and free Indo-Pacific region, adding: “our commitment is to stand with countries across this region who are anxious to partner with us for security.”

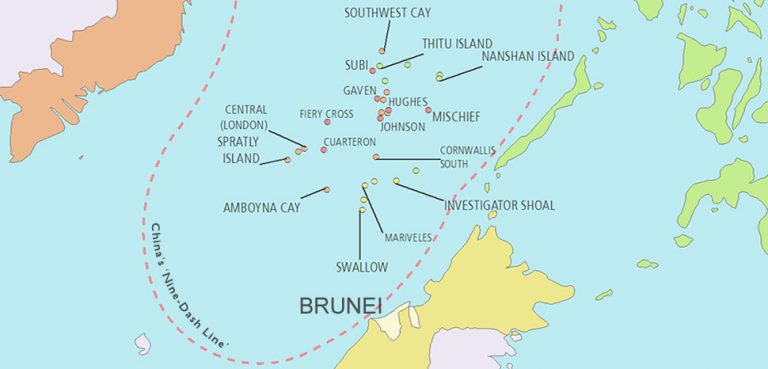

The intended audience here is obvious. On one level the Lombrum naval base agreement is a signal to China that its expansive policy in the Indo-Pacific (and elsewhere like the South China Sea) will not go unchallenged by the United States. But even more importantly, the new base is meant to send a signal to regional middle powers like Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, Australia, etc., that the Indo-Pacific remains a fixture in long-term US strategic planning. In essence, it’s the same rationale that underpinned President Obama’s ‘Asia pivot,’ although events in the meantime – mainly China’s expanding military power and the collapse of US regional initiatives like the TPP – have made it harder for the United States to make its case to anxious potential partners.

We won’t know just how much of a hard power impact the Lombrum naval base will have until the details of the upgrades and stationing plans are made public. However, it is still highly significant as a reflection of evolving US-Australia military cooperation.

A blow to China-Australia relations. The base plan is even more significant when one considers the recent trajectory of China-Australia relations. Broadly speaking, Beijing has been seeking to drive a wedge between Canberra and Washington, and its cause has been greatly helped by the growing significance of China to the Australian economy and the United States’ insular focus in the early days of the Trump administration. China is now Australia’s leading trading partner in terms of imports and exports, and both countries are vital to the economic health of the other. However, there have been growing concerns within Australia over Chinese influence in the economic and political spheres. These worries came to a head during a high-profile covert influence scandal that precipitated the 2017 resignation of at least one MP who had apparently been compromised by China. A new package of anti-espionage and anti-foreign subversion laws has now been passed, which aim to curb the ability of Beijing and other governments to indirectly influence the Australian political process.

The influencing scandal will reverberate in China-Australia relations for years to come. For certain Australians, China will be viewed as a meddling and antagonistic force – a rising power that needs to be balanced against. For certain Chinese (and some Chinese-Australians), the whole affair is based on flimsy evidence and reflective of a deep-rooted anti-China bias.

Whatever the case, the events of 2017 have had a profound freezing effect on China-Australia relations. The announcement of a new co-developed naval base on Manus Island will do nothing to help thaw them out. In fact, China has already announced a new anti-dumping probe on imports of Australian barley just hours after the naval base revelation (China accounts for around $877 million worth of barley sales annually).

Bringing the fight to the economic front in the Indo-Pacific. The Lombrum naval base announcement was flanked by a barrage of new development initiatives, and its these that could well prove to be the game-changer in the end. Japan has offered $10.6 million for new educational initiatives and the United States, Japan, New Zealand, and Australia have pledged to bring electricity to 70% of Papa New Guinea’s people by 2030 (up from the current 20%). The group of four donors also suggested that similar financing packages might be extended to other Indo-Pacific countries that “support principles and values which help maintain and promote a free, open, prosperous, and rules-based region.”

Again, it’s obvious who the intended audience is here.

China has been profligate in its financial assistance to Pacific island nations in recent years. Yet much of the financing has come in the form of no-strings-attached concessionary loans that are susceptible to graft and are too-often directed at projects with little long-term economic benefit. The end result in many cases has been a growing pile of unsustainable debt for Pacific island nations.

Though there are drawbacks to the Chinese approach, it should be said that the loans are often accepted because there’s no other financing on offer. In other words, it’s theoretically better to build a highway at 15% interest than not to have it built at all (though in practice it’s often a road to nowhere).

Herein lies the real motivation behind the PNG electrification push. Quad powers are now becoming acutely aware of the linkages between development assistance and military facilities (a linkage made exceedingly clear by Sri Lanka’s experience with the Hambantota port). Australia in particular can’t take its preeminent position among Pacific island nations for granted anymore. And by cooperating and coordinating with other likeminded states, Australia can mitigate some of the financial burdens of trying to compete with Beijing in the Indo-Pacific. There are two ultimate goals here: to forestall the encroachment of Chinese hard military power in the immediate vicinity of Australia, and to promote a more transparent, rule-based approach to development funding (one that will, in theory at least, foster greater stability in the region).

Just how sustainable Quad engagement is on the development front remains to be seen. But so long as Canberra, Tokyo, and Washington seek to roll back Belt and Road gains in the region, the real winner will be the island nations, which will be able to play the two sides off against each other and secure more favorable terms for much-needed development financing.