Summary

The Obama administration has rebooted bilateral relations with yet another international pariah, in effect choosing engagement over the morally sound though geopolitically risky course of self-imposed isolation.

Analysis

Emphasizing the carrot over the stick is emerging as a common thread in President Obama’s foreign policy. Sudan has now joined Burma and Iran to form an impromptu ‘axis of reconciliation.’ This latest shift towards engagement is sure to incense portions of President Obama’s activist support base, as it contradicts much of President Obama’s hard-line campaign rhetoric on Sudan.

Shifting gears towards engagement with Khartoum is a decision born out of practical considerations, mainly, the lack of real policy options in regards to using unilateral coercive force. A hallmark of American decline, both in soft power and the effectiveness of American hard power, has been Washington’s inability to effectively coordinate multilateral pressure against pariah states. In the case of Sudan, the amoral foreign policy posture championed by several BRIC countries affords Khartoum a lifeline with which it can escape pressures from the United States and the EU. Without any hope of coordinated multilateral pressure, the Bush-era Sudan policy is tantamount to a self-imposed isolation, and as Secretary Clinton recently put it, “sitting on the sidelines is not an option.”

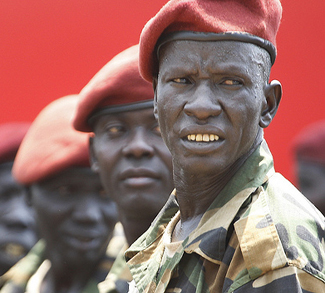

That isolation is no longer acceptable reflects the high stakes scenario that’s currently playing out in Sudanese politics. Washington’s new policy of engagement is primarily aimed at stabilizing Sudan ahead of crucial national elections in 2010 and a referendum on independence in Southern Sudan a year later. Secondarily, engagement could eventually provide more space for American companies to muscle in and compete with China over Sudanese oil.

The Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) is causing a great deal of anxiety for bureaucrats in the State Department. The CPA ended the Second Sudanese Civil War in 2005, laying out a series of steps that lead to a referendum on independence in 2011. Now, time is running out and there are several legal hitches that could lead to conflict down the road. With less than two years left, Khartoum has yet to conduct a census to determine whether populations fall into the North or South. Even more troubling is the lack of any agreed upon procedure for the referendum, such as how many votes are required to trigger Southern independence.

If the process envisioned by the CPA breaks down, then it is likely that civil war will once again descend over Sudan. Given some of the countries in the neighborhood – Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and the DRCongo – a civil war in Sudan could fast spill out from its borders and destabilize the entire region.

The Obama administration has concluded that the appeal of America’s carrots can exert more influence than the threat of more sanctions or American military power. Washington can offer much in the way of incentives, ranging from the removal of Sudan from the terrorist list to scaling back existing sanctions. Also, since the list of benchmarks for success remains classified, the media will have a hard time holding the administration to account.

China may serve as a useful ally in averting civil war. Beijing’s ‘business first’ approach to international relations has long made the Darfur conflict irrelevant in Sino-Sudanese relations, nevertheless a civil war represents a serious threat to China’s sizable business interests in Sudan. Sudanese oil exports to China have been increasing rapidly since 2003, and now constitute over 6% of China’s overall oil imports. Moreover, China is Sudan’s largest trading partner and also sells arms to Khartoum.

From here on out, all international players will be shifting their focus towards the CPA while casting a wary eye towards 2011, a year that will have a decisive impact on Sudan’s future.