Donald Trump’s moves to cut American health spending overseas have met with considerable criticism, but none as damning as that of the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. In a report released last month, the Academies lay out the security implications of global health crises in stark terms. Were a major pandemic to strike today, the death toll in the United States alone could reach 2 million – twice the number of casualties the country has suffered in wartime in its entire history.

Because such a pandemic is only a matter of time, the authors of the report call for continued U.S. leadership and investment in global health. One key recommendation is for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to do more to improve public health capacity in low- and middle-income nations.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration is not listening. In his first major budget hearing since taking office as Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson defended Trump’s demand for a 28% cut in funding for the State Department and USAID projects, telling the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the government will “ask other donors and private sector partners” to compensate. “Even with reductions in funding, we will continue to be the leader in international development, global health, democracy and good governance initiatives, and humanitarian efforts,” he told lawmakers in a prepared statement. “If natural disasters or epidemics strike overseas, America will respond with care and support.”

It would, of course, be a mistake to dismiss the private sector’s role entirely. Ideally, public and private actors should be able to combine their capabilities in pursuit of rapid crisis response.

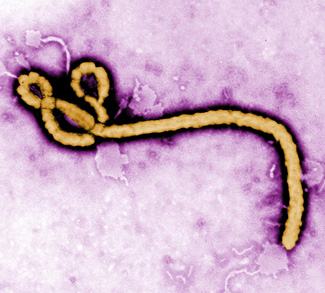

Yet the assumption that epidemics that “strike overseas” will necessarily stay overseas is misguided. In today’s thoroughly globalized world, the chances of infectious diseases erupting and spreading rapidly is greater than ever – with the Ebola and Zika viruses providing two textbook examples in recent years. Given that it is only a question of “when” another global pandemic will hit, strategies need to be put in in place to contain and stamp out outbreaks as quickly as possible.

Despite Tillerson’s assertions that private sector partners can pick up the slack left by budget cuts, this is an effort best led by government. Private interests cannot be expected to devise long-term, strategic healthcare decisions for the entire planet. As the National Academies of Sciences put it, governments like the U.S. have a special obligation to continue investing in these initiatives both domestically and abroad – not just as a matter of philanthropy, but also as a matter of economic stability and national security.

It would, of course, be a mistake to dismiss the private sector’s role entirely. Ideally, public and private actors should be able to combine their capabilities in pursuit of rapid crisis response. The West African Ebola outbreak produced important examples of this dynamic at work. In Guinea, for instance, Russian mining company UC Rusal built and invested $10 million in a comprehensive medical facility, the Center for Microbiological Research and Treatment of Epidemic Diseases, in the city of Kindia. The facility operated as a hospital for the treatment of Ebola patients during the height of the crisis, but also as a center for testing a promising vaccine later developed by scientists with support from the Russian government. With some 1,500 employees in Guinea, the company was able to leverage its significant on-the-ground presence on behalf of the wider regional response.

Public-private partnerships also played a key role in the drive to tackle Zika, a virus that has been linked with microcephaly in infants and the source of a health scare before the 2016 Olympics. In July 2016, French pharmaceutical company Sanofi teamed up with the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in the U.S. and, in a separate deal, with the Fiocruz public health center in Brazil to speed up development of a vaccine. The partnership with the Army research team granted Sanofi access to the most advanced version of the vaccine and enabled the company to share it the Brazilian public health center, which assisted in pre-clinical and clinical trials and other aspects of its production.

UC Rusal and Sanofi provided key support for developing vaccines, but each was part of a wider response that only succeeded through collective effort. The fight against Ebola, for example, saw Doctors without Borders (MSF) take a frontline role while the State Department and USAID worked together to mobilize aid to West Africa in response to the outbreak. It was also in Western African countries with more robust national healthcare systems that the outbreak was contained relatively quickly. Nations with weaker systems, like Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea, bore the brunt of the epidemic. Without sufficient investment in overseas healthcare systems and initiatives, it might be impossible to contain another crisis like Ebola in the future – even if private actors take on a leading role.

The first-ever meeting of the health ministers of the G20 economies, which took place in late May, surmised as much. Speaking ahead of summit, German Health Minister Hermann Gröhe said governments need to collaborate more to minimize the risk posed by potential pandemics. He warned that the world risks reverting to the pre-penicillin era if leading states do not work together to fight the threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, financing research, and backing the development of alternative medicines.

By slashing funding for the very agencies on the front lines of global health – not just the State Department and USAID, but others like Health and Human Services – the Trump administration is sending a dangerous message about Washington’s commitment to this fight. The U.S. must invest more, not less, in both domestic and overseas healthcare spending. Otherwise, no ocean is wide enough to protect the country from the next global pandemic.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.