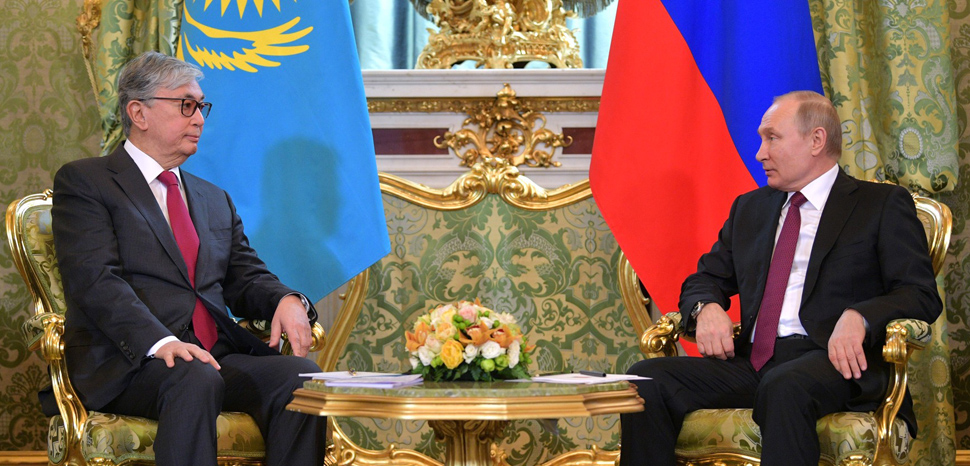

As thousands of Russian boots hit the ground in Ukraine and bombs started decimating cities, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy adorned his military fatigues and with them the respect and admiration of millions worldwide. In early January, when Kazakhstan faced its own crisis – albeit one of a very different nature – President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev responded by distancing himself from his people and cozying up to Vladimir Putin.

It is said that history rewards the modernizers. In the face of existential crisis, this truism is at its most stark.

During recent unrest in Kazakhstan, the embattled Tokayev issued a shoot-to-kill order that put his own citizens in grave danger, then invited Russian troops to restore order. Thousands of peaceful protesters and several high-profile political figures including former Prime Minister Karim Massimov were arbitrarily detained. There have since been widespread accounts of mistreatment and the authorities have admitted to multiple deaths in custody by torture.

Will President Tokayev venture deeper into Moscow’s orbit, or will he take heed of modernizing voices? Will he look at how the world is rallying behind the comedian-turned-political warrior and reassess his policies? His success, and ultimately his political longevity, will depend on his ability to escape Putin’s stranglehold and how seriously he treats civil liberties. Recent trends and the violent Moscow-endorsed crackdown which claimed hundreds of lives bode ill for Kazakhstan.

There is now a veneer of stability: order has been restored, at least temporarily, and the Russian troops have come and gone. A charm offensive, led by the Kazakh foreign minister, was intended to show the government is tackling the root causes of the protests by beefing up employment opportunities for Kazakhstan’s restless youth.

Tokayev will need to go beyond stop-gap measures however to restore trust at home and abroad. In particular, he will need to demonstrate in tangible terms that he is sincere about respecting basic human rights and civil liberties, and is making decisions with independence from the Kremlin. A major speech on reform this week was expected to contain concrete action, but ultimately felt like little more than President Tokayev asking for more time and more trust from a population short on both.

In the first instance, he must address concerns raised in Brussels by the European Parliament’s resolution, which condemned the Kazakh leadership for stifling fundamental freedoms and failing to distinguish between peaceful protestors and violent provocateurs. These concerns have been echoed this week by Michelle Bachelet, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, during the 49th session of the Human Rights Council. She pointed to urgent human rights questions that remain unanswered two months after the events. How many of the thousands of detainees have been mistreated or tortured? What are the grounds for their ongoing detention? Will they be granted their full due process rights?

Without convincing answers, the international community is left to fear the worst for modernizing forces such as Massimov, until recently the head of Kazakhstan’s National Security Committee, who was arrested in early January on trumped up charges of high treason. The two-time prime minister has been held in solitary confinement, denied access to his family and medical care despite suffering from serious health issues. In the pre-trial phase and under a spurious “top secret” classification, there is a legitimate fear of a decades-long sentence brought against Massimov, one of the key architects of the post-Soviet Kazakh state.

In government, Massimov pushed through reforms that propelled Kazakhstan’s growth as an innovative, middle-income country. He helped spur Kazakhstan’s digital transformation, subscribing to the freedoms created by the internet. Massimov and fellow modernizers understood that Kazakhstan’s future depends on its ability to build a knowledge economy that is in-sync with the world’s top performing countries. A vocal champion of the English language in Kazakh schools and universities, Massimov looked to Singapore as a model to emulate in the fields of healthcare and education, inspiring the creation of Nazarbayev University.

His continued detention and the deprivation of his rights to due process are a source of great pain for his family, friends, and colleagues. These various factors are why I decided to submit Karim Massimov’s case to the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention for investigation. Under the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, this body is empowered to review cases of arbitrary deprivation of liberty and ultimately adopt opinions.

For all its faults and contradictions, Kazakhstan was until recently on the right track, gradually edging closer to Western norms and standards. This hard-earned progress is now at risk as President Tokayev slides back into Russia’s orbit. International and frontier investors who bought into Kazakhstan’s modernization are reviewing their stakes and the prospect of a stark fall in FDI looms large. With or without Russian troops on Kazakh soil, Putin’s shadow looms large over the Central Asian state. Devoid of modernizers and bridge builders in the Massimov mould, Kazakhstan’s independence vis-à-vis Moscow is in jeopardy.

The future development of Kazakhstan will depend on President Tokayev’s next steps. He has access to a strong instrument in his hands to clear his name and give a new start to the country: allowing an international, open, and transparent investigation or declaring an amnesty to all those arbitrarily detained in the January events. He will need the support of a big tent of negotiators who can leverage interests with China, Russia, and the West, while keeping the peace at home between Kazakhs and ethnic Russians. This will be no easy feat, but the alternative is a society torn at the seams, in constant conflict with itself and others.

David. A. Merkel has served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs and Director for South and Central Asian Affairs at the National Security Council in the White House. He is a founding pro-bono member of the Board of Trustees of Nazarbayev University in Nur-Sultan. He is an Associate Fellow at IISS.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com