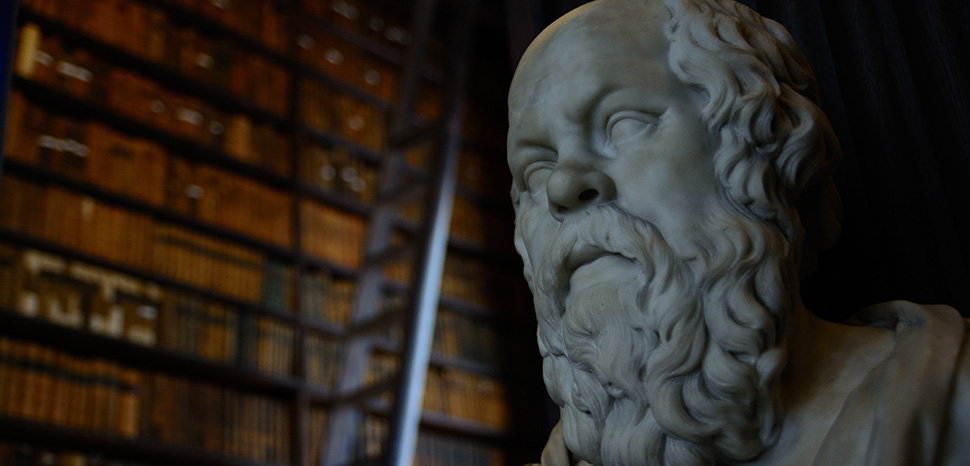

To read the Czech philosopher, Jan Patocka, one needs to dispose of concepts and categories, and approach philosophy, politics and history anew. It is the phenomenological essence – to transcend the metaphysics of the old and reapproach the idea of being. Patocka sees modern being as located in technicity and war; that the scope of history, far from being one of progress and ‘end of history’ utopia, is regressive, not in the sense of a Rousseau state of nature, but must be located back in pre-history and the fateful day when man left the home and entered the ‘polis.’ Central, therefore, is the need to resurrect the idea of the ‘good’ and for a morality preceding us and proceeding. Patocka, the signatory of Charter 77, became the Socrates of the twentieth century after his death at the hands of the Police in Czechoslovakia. Asserting that human rights preceded the polis, the state, the totalitarian regime. This ‘care for the soul’ is what epitomises Greek thought. Greek thinking was nature bound, at first Dionysian, fixed in its limits. Man gave up the ‘care for the soul’ in a Faustian pact with ‘having.’ In this Icarian leap, the modern Faust rejected God and stands on the Nietzschean abyss in a constant war against all. Patocka writes:

‘The soul can either, in its care for itself, give itself fixed shape (feste Gebilde) or it can, neglecting itself and eschewing all education, abandon itself to the indefinite, to the lack of limits inherent in desire and pleasure.’

The sense of the soul is omnipresent and gives Patocka’s thought a religious element. The care for the soul represents the ‘good’ of Plato’s immortality, or the ‘telos’ of Aristotle (a life with purpose). For the Romans, ‘Law’ became the jurisdiction of the soul, a way to enable empire. In the Christian era the good became redemption, salvation. This is the dilemma for Patocka, at once because he construes care for the soul’ as a particularly European thing and also that this ‘care’ can take on different forms. The ‘fall’ for Nietzsche was one into nihilism, in that once man had abandoned God, the wasteland of eternity yearned. Whilst Husserl had seen the ‘lebenswelt’ (nature world) as ‘invariant’; that ‘being’ exhibited a primordial constancy, Heidegger introduced the idea that the lebenswelt was, in fact, historicist. Being, or ‘dasein’ is ‘epoch specific’, and has different concerns. This ‘historicity’ means that our encounters of the world will vary according to the epoch. This affects are thinking. We don’t perceive like the Greeks. Yet the problem of the modern world view is that there is a lack of concern for consciousness, for care for the soul. This has resulted in the barbarism and nihilism of the twentieth and twenty first centuries. War is now the dominant culture of the twenty first century.

‘In all human uncovering of being, originating in history, there emerge ever new historical worlds.’

Patocka follows Husserl’s phenomenology and concern with the meaning of history. In this history has a teleological continuum in which meaning is passed down generation to generation. Here phenomenology assumes a very European structure and Husserl, Heidegger and Patocka are essentially Euro-centric thinkers although not in the sense of geography. The crisis of the modern world is rooted in the past. Modern man inhabits two worlds, the ‘lebenswelt’ or natural world but also another scientific, technical world which pushes man further away from the ‘care for the soul.’ The dilemma posited by Patocka is the separation of the historical world from the pre-historical world. He wants to look back at the point where ‘consciousness’ was relegated and the scientific, rational world took over. Like Husserl’s ‘epoche,’ one needs to suspend the ‘scientific rational’ fog and to see the clearing of Heidegger when the mist lifts and the pre-historic consciousness is exposed. The concept of historicity was unveiled by Hegel in the notion of the specificity of consciousness; in different epochs a specific consciousness occurs. In pre-history, which Patocka situates in the era of Platonic questioning, history then took on its problematic identity. Rather than ‘accepting’ the Gods, man begins to question them.

‘Once, however that question had been posed, humans set out on a long journey they had not travelled hitherto, a journey from which they might gain something but also decidedly lose a great deal. It is the journey of history.’

So, the question of freedom begins its gushing flow from the high mountain river of the gods and speeding through epochs – each one is defined. For the Chinese this means freedom for the one, the emperor; for the Greeks there are the few, and from the Enlightenment began the idea of the freedom of all men. Now the Hegelian dialectic of history sees this unfolding of history and freedom as an ‘end of history’ cul de sac. For Hegel the pinnacle of history was the Prussian state. The ideal state is the Kantian one whereby the laws represent the will of the people. This is at odds with, for example, the Spenglerian view of history as decline. The Hegelian view posits the individual ‘in’ history; man, acting in history can transform history itself. Man, in history, uncovers ‘being’ by acting in the world. This occurrence, for Patocka means:

‘For living beyond oneself, for legend, for glory, for endurance in the memory of others.’

For Heidegger this means the spirit of authenticity emerges. For Patocka it signifies the free and equal engagement with the world, not dominated by toil, but excellence, not by telos but by choice. It means that the ‘polis’ must be about free and equal speech, by persuasion, not control. Whilst for Husserl the individual is a ‘disinterested observer’ – for Patocka the individual engulfs himself in the stream of history, partakes in the tragedy, the glory. This Patocka takes from Heidegger. This partaking in events impinges on our view of the present. Increasingly, humanity is removed from partaking. This uprootedness, this alienating factor occurs as ‘technics’ and the nature of globalised worlds and their administration-removes the majority from ‘being in the world.’ This view (which was predominant with the likes of Marcuse and the Frankfurt School of Marxism) saw alienation in the structures of the world. Liberation is through new structures ostensibly administered by the liberals of the Frankfurt School. Yet this, for the left, is the ‘dialectic of enlightenment’ where the liberation of the Enlightenment produces the materialism, the technics, which strangles the world. This dialectic has also produced an administration, a state of terror, where ‘liberal’ government erodes and demolishes ‘being.’ Man becomes Arendt’s ‘Homo laborans,’ toiling for sustenance. The political class exists therefore in a master/slave relationship with civil society. Modern bureaucracies work in an extractive quality and become hegemonic by monopolising ideology.

For Patocka, ‘the result of the primordial shaking of accepted meaning is not a fall into meaninglessness but, on the contrary, the discovery of the possibility of achieving a freer, more demanding meaningfulness.’ After pre-history humans take hold of the reins from the Gods. With this new responsibility, ‘history’ starts. Here Patocka differs with, for example Heidegger’s view of history. For Heidegger being now is ‘standing out’ from existent meaning and awaiting the next revelation. This was put into action through Heidegger’s belief in a meaningfulness of National Socialism. For Patocka it is the polis, the political engagement, an active role. Plato’s thought established the conception of eternal forms so that the ‘good,’ ‘truth,’ etc. are fixed in eternity. The phenomenological, that of Heidegger and Patocka, sees meaning (being) morphing through history, through epochs. It is mutable, to be acted on. Yet now, ‘metaphysical’ thinking (that which doesn’t change) inhabits the most modern of epochs post-Enlightenment. These immutable modes occupy science, reason, Marxism. They are largely invisible to us. They are abstract, mathematical. This is the epoch we now occupy. The true world of forms, again. The ‘appearing’ world has been subsumed. This scenario seems nihilistic; the absence of meaning within material and technological civilisation. Being, according to Patocka ‘can never be explained by a thing.’

Therefore, the post-Christian era suffered anew another ‘shaking of meaning.’ Humanity lives ‘with a sense of absolute meaninglessness, and if mathematical natural science..represents…the norm of what there is, then it is understandable that for all the expansion of the means with which to live, our life is not only empty but at the mercy of the forces of destruction.’ Science, as Husserl had outlined previously in ‘Crisis of the European Sciences,’ became the Nazi project – a culmination of Enlightenment sanctification of reason, of science. Patocka sees the modern era as a rapid accumulation of force and energy which is expunged in periodic wars. War is ‘de rigeur’ for modernism. It is ‘military Keynesianism.’ Yet Patocka does not succumb to Nihilism. He attempts to find a way out through a ‘questioning’ of the lack of meaning. From this position human beings are forced to search for meaning through the Socratic questioning of the ‘polis.’ Human beings here are active and partake in history. The phenomenological method is the Heideggerian ‘being in the world,’ but for Patocka it is not the ‘waiting for death’ of ‘Dasein’ but a more open response and the ‘care for the soul.’ In Patocka’s view this ‘care’ is not derived from outside, from empirical, scientific modes. In this Patocka, foresaw the dilemma of technology and rationality, its suffocating denial of the soul.

‘Modern ideologies objectify the open horizon and thus create an enclosing horizon that needs to be broken through, in order to find the true openness of the horizon of time.’

Yet Patocka’s vision was incomplete. Based on a European and Greek perspective, it neglected a new globalised world. The unfolding of the late twentieth century and twenty first century have, at once, proven the Patocka vision, but also accentuated its crisis. That this rationalism has spiralled into meaninglessness is visible in a globalised commodification of the world where ‘care for the soul’ becomes impracticable and due to the scarcity of resources, war takes on an even larger role. The objectifying of the horizon of the future is a particularly damning feature of modernity, in the omnipresent feature of Marxist logic which has permeated all aspects of a ‘end of history’ horizon making. The liberal world, steeped in materialism and glued to the logic of the past cannot be ‘open’ to new ideas. A putrefying loss of self-criticism in academia, in culture, in thinking entombs the present. The contradictions of materialism, ecology, consumerism produces a grand spectacle of decay. The ’dialectic of enlightenment’ shutters the world into darkness, where spaces for phenomenological partaking are closed off, in elite entrapment of freedom.

The US debacle in Afghanistan could result in the death of millions of children. This is now a side show to the Ukraine theatre. The common theme in the wars, from Afghanistan to Haiti is resources and strategic dominance. The US agreement with Australia (Aukus) to enable the manufacturing of nuclear submarines to combat China is echoed in Iran where nuclear proficiency beckons. In Yemen the fight is about the oil and gas in Marib. Meanwhile in Haiti -Jimmy ‘Barbecue’ Cherizier, a gangster who kidnaps oil terminals, provides the ‘comic interval’ on a global tragedy.

It is the ‘polemos’ which Patocka predicted. Polemos was the Greek symbol of war, of night. Patocka contrasts day and night; the day is uncontested being, accepted life. It is night, ‘polemos’ which we now have entered. Removed from the certainty of pre-history and its cyclical being and divine solace, man has accepted the ‘problematic’ of a world where meaning needs to be solved. With Christianity there was a return to a kind of solace and then the Nietzschean wasteland. There is no doubt a Spenglerian cycle is complete and man must refind himself in a new being. The Enlightenment era is over and Patocka’s ‘care for the soul’, the Platonic ‘examined life’ must be redrawn on the canvas of epochs, amidst the sounds of shell fire. The ‘shaken,’ the people thrown into the polemos of modernism must themselves reject and take back their past and future from elites, having, and universalism. The spirit of Heraclitus, of grandeur, of authentic being is there waiting for a shepherd. In the Greek myth ‘War and his Bride’ Polemos eventually marries ‘Hubris’ (Arrogance), and in this is a warning to humanity….

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com

Brian Patrick Bolger studied at the LSE. He has taught political philosophy and applied linguistics in Universities across Europe. His articles have appeared in ’The National Interest’, ‘Geopolitical Monitor’, ‘Voegelin View’, ‘The Montreal Review’, ‘The European Conservative’ ,’The Salisbury Review’, ‘The Village’, ‘New English Review’, ‘The Burkean’ , ‘The Daily Globe’, ‘American Thinker’, ‘Philosophy News’. His new book, ‘Coronavirus and the Strange Death of Truth’, is now available in the UK and US.