While the world’s attention has been firmly fixed on Greece’s debt crisis and the “Grexit” threat, there is trouble brewing much closer to home. Staying largely in the Greek shadow, Puerto Rico is on the brink of defaulting on its debts. The parallels with Greece are unavoidable, and not just on account of the timing, so it is worth taking a deeper look into whether Puerto Rico is the United States’ own Greece and if its looming debt default could potentially have similar repercussions.

Background

What has been going on with Puerto Rico? In short, once a prosperous Caribbean nation, in the past decade Puerto Rico has seen its economy shrink considerably. This trend, the growing migration of citizens to the mainland, as well as the island’s labor policy, have all conspired to create the perfect storm for Puerto Rico.

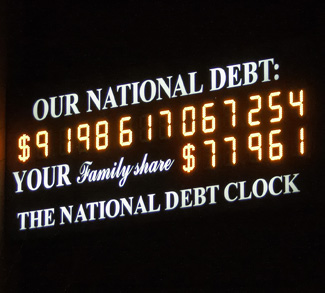

Jumping to present day, Governor Alejandro Garcia Padilla recently told the New York Times that the nation’s $72 billion debt was ‘not payable,’ while Reuters quoted Moody’s as warning that the probability of Puerto Rico defaulting on its securities was approaching 100 percent.

Much like Greece, Puerto Rico has been asking its creditors for debt relief, and much like Greece, it relies on a much wealthier economy to the north. The island’s debt, owed to a combination of creditors, is higher per capita than any US state.

Default Repercussions

With Puerto Rico’s default almost certain, one cannot help but wonder about the potential impact on the US economy, especially given the parallels with Greece and the chaos which the Grexit could unleash not only on the Eurozone but on the world.

In addition to disrupting the life of Puerto Rico’s citizens, the repercussions of a default would ripple through the traditionally low-risk bond market, impacting investors such as retirement funds.

Dante Disparte, founder of capital management firm Risk Cooperative, recently told The Huffington Post that a $73-billion write-off had the “potential to bring down many more aspects of the economy than we might let on, because we are trying to treat it like it’s isolated and that it’s an island, but it’s a dollar-denominated economy.”

MarketWatch in turn quoted Daniel Hanson, an analyst at Height Securities, as commenting in a note that “the signal from breaking a seven-decade streak of bond payments may imply more defaults are looming”.

Hedge funds, known as heavy buyers of Puerto Rico bonds, are bound to take a beating too. According to The Wall Street Journal’s analysis of data from Morningstar Inc, OppenheimerFunds Inc and Franklin Advisers Inc for instance together owned about $10.8 billion face value worth of bonds, representing 15 percent of Puerto Rico’s debt as of March 31.

Banks Breathing Freely

And yet, as far as financial turmoil is concerned, the similarities between Puerto Rico and Greece seem to end here. While the Grexit threat has caused serious concerns for European banks, prompting them to reduce their exposure to Greece, US banks have little cause for worry. Wall Street is not exposed to Puerto Rico debt and would not feel the impact of a default to the extent that European lenders would if Greece continues defaulting on its debts.

John Cochrane, a professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, recently compared the two situations in an article on his blog, “The Grumpy Economist,” commenting that the big lesson from the Greek drama was that sovereign debt must be able to default in a currency union, without shutting down the banks.

“There is no question of PRexit, that people wake up one morning and their dollar bank accounts are suddenly PR Peso bank accounts,” he pointed out.

In addition, despite Puerto Rico being a dollar-denominated economy, there is hardly any risk for a “spillover” to other economies, nor is there a threat to the US dollar as a currency, unlike the euro whose very existence is threatened if one nation leaves the euro zone. A proof is Detroit’s bankruptcy in 2013 which, while considerably smaller, did not trigger financial contagion.

Definitely Not Greece

While Puerto Rico’s default will cause a certain degree of financial turmoil, just like the default of any country, and will be felt to some extent in the north as well, it will not spell the same disaster for the United States and its banks as Greece would to the rest of Europe. Or in other words, it is much closer to home, but is much less dangerous.

Zachary Cohen is the Managing Director of the Finance Institute.