With the release of Japan’s new National Security Strategy (NSS), we have seen a chorus of commentators discuss the new strategy from the viewpoint of departing from Japan’s pacifist constitution. The Hindustan Times calls it a game-changer, whereas the China Daily called the new strategy “disconcerting.” In a statement in the Global Times by a spokesperson of the Chinese Embassy in Tokyo, responding specifically to language describing China as the “greatest strategic challenge ever,” the official strongly protested: “saying such things within the documents severely distorts the facts, violates the principles and spirit of the four China-Japan political documents, wantonly hypes the ‘China threat’ and provokes regional tension and confrontation.”

Allies of Japan including the US, Canada, and Australia have welcomed a more proactive and 21st century NSS. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Japan Chair Chris Johnstone calls it transformative by “shattering policy norms in place for much of the period since World War II.” In contrast, the United States Institute of Peace’s Senior Policy Analyst Mirna Galic stresses that “the name is new, but the document is really the latest update of the intermittently released National Defence Program Guidelines, which were last updated in 2018. Similarly, the new defence build-up plan is an updated version of 2018’s Mid-Term Defense Program.”

In reality, the new NSS is both transformative in focusing on counterstrike capabilities and boosting defence spending and consistent with Japan continuing to be deeply wedded to its longstanding commitment to being a peace-loving nation. The NSS highlights that Japan has a decades-long record of accomplishment of maintaining a basic policy of an exclusively nationally defence-oriented policy. This includes not becoming a military power that poses threats to other countries. Importantly, Japan remains committed to observing the three non-nuclear principles of not producing, possessing, or allowing transit of nuclear weapons through Japan.

This position was re-informed at the Shangri La dialogue in June 2022 by Prime Minister Kishida Fumio in which he launched his Kishida Vision for Peace. There again, he stressed that Japan will never acquire nuclear weapons and it will retain its non-nuclear principles.

Seen alongside the year-by-year 10% plus increase in military spending between 2000-2010 and the latest increase of 7.1% for fiscal year 2022 in China reaching about $229 billion UDS in 2022, Japan’s modest increase to 2% of GDP over five years seems inadequate to deal with the growing challenges associated with China’s rapid militarization. In fact, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute [SIPRI] in April 2021, “China’s military spending increasingly dwarfs that of its neighbors. For example, China now spends more on its military than Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and India combined.”

Considering the failure of Article 9 of the Japanese pacifist constitution to halt or positively influence the successive military budget increases by Chinese counterparts, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the decades-long process of North Korea building weapons of mass destruction, the new NSS is a realistic approach to mitigating the increasingly severe security challenges within the region. This conclusion becomes even more self-evident when we reflect upon the North Korean testing of a plethora of different missile systems and launch vehicles into the Sea of Japan and over Japan as well as the military threat towards Taiwan.

Critics will argue that the Liberal Democratic Party with this new NSS has been able to find a loophole in Japan’s legislation to overcome the limitations associated with Article 9 of Japan’s constitution. Others suggest that “it’s a hard time to be a Pacifist in Japan nowadays” intimating that pacificism is disappearing in Japan as it lurches to right of center.

As a matter of fact, the strategy is based on an adherence to the Japan-US Alliance as the cornerstone of Japan’s security in the Indo-Pacific. This includes prioritizing cooperation with like-minded countries in line with a defensive approach to dealing with Japan’s challenges within the region.

Calling out China as a strategic challenge in new NSS is consistent with the conclusions of many states. Canada’s recently released Indo-Pacific Strategy labels China an increasingly “disruptive global power.” The US is more explicit in its Indo-Pacific Strategy suggesting that “China is combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological might as it pursues a sphere of influence in the Indo-Pacific and seeks to become the world’s most influential power.” The EU and ASEAN are more sanguine in their respective Indo-Pacific frameworks. The EU stressed that it “will promote an open and rules-based regional security architecture, including secure sea lines of communication, capacity-building and enhanced naval presence by EU Member States in the Indo-Pacific” while ASEAN stresses the “strengthening ASEAN Centrality, openness, transparency, inclusivity, a rules-based framework, good governance, respect for sovereignty, non-intervention, complementarity with existing cooperation frameworks, equality, mutual respect, mutual trust, mutual benefit and respect for international law, such as UN Charter, the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, and 3 other relevant UN treaties and conventions.”

The common thread explicitly or implicitly articulated in these various documents is that the rules-based order is being challenged and that each country, union or association must work to preserve the post-WW2 order that has been the foundation for the stable, peaceful development, and prosperity that the Indo-Pacific has become dependent on.

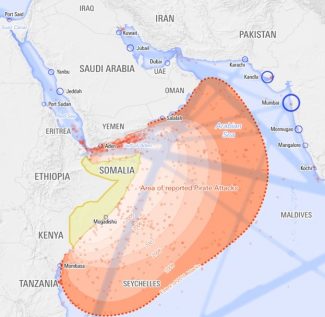

Japan’s post-WW2 approach to dealing with security challenges within the region – including economic engagement, diplomacy, overseas development aid (ODA) and investment of FDI into the Indo-Pacific region – has not accrued the same benefits for all regional players. In the case of China, North Korea, and Russia what we have seen is China move from a position of reform and opening in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s to a rapidly militarizing country that has created artificial islands and militarize those islands in the South China Sea, threatening sea lines of communication for not only Japan, but Southeast Asian countries, the United States, as well as other countries that use the South China Sea to ferry their goods in and out of the region as well as energy resources.

As late as this summer, China engaged in military exercises in and around Taiwan, launching five ballistic missiles into Japan’s EEZs, and continues to send ships that are heavily armed coast guard vessels into the waters around the Senkaku Islands. North Korea also continues to build its weapons of mass destruction and launch vehicles. This is despite numerous efforts to engage in diplomatic initiatives to find a solution to the differences that lie between North Korea as well as the stakeholders in the region, including South Korea, Russia, China, United States and Japan.

Lastly, Russia with its invasion of Ukraine has demonstrated that Japan’s approach to security in the post-WW2 period needs a fundamental rethink. The national security strategy is that fundamental rethink recognizing the importance of working with like-minded countries that focus on rule-of-law, human rights, democracy, and stability. Japan’s security is inextricably linked to a stable rule-based international order, an order that has brought prosperity, peace, and stability to not only Japan but to the Indo Pacific region and beyond.

The new NSS invests in the current rules-based order instead of deviating from it. Through this strategy, Japan wants to prevent Chinese hegemony emerging within the region.

Notwithstanding, Japan has been consistent fostering engagement through trade policies that include China such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) but at times exclude China such as the Comprehensive Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Japan continues to build multi-layered and multilateral partnerships throughout the region. This includes the Japan EU-Economic Partnership Agreement and trade agreements with the United States. It continues to advocate for digital agreements within the region and it continues to invest huge amounts of resources in terms of ODA and FDI to help build infrastructure and connectivity in Southeast Asia and South Asia in order to make these regions more strategically autonomous so that they can make different decisions when it comes to code of codes of conduct in the South China Sea and dealing with diplomacy in general within the region.

Stephen R. Nagy is a senior associate professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a senior fellow at the MacDonald Laurier Institute, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs

*Article originally published on December 22, 2022.