The recent oil transit deal between Sudan and South Sudan, which is expected to come into effect by the end of this month, does not symbolize a fundamental change in each country’s attitude towards the other, nor will it herald a new era of closer cooperation. While the deal itself will likely be upheld without too many further snags, it is most easily understood purely in terms of self-interest. Collaboration between the two countries regarding their numerous other disputes will remain elusive.

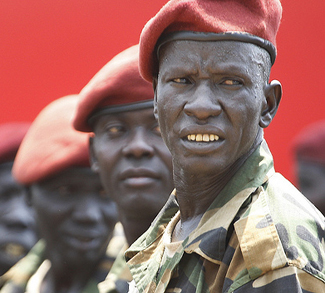

South Sudan has been a semi-autonomous region of Sudan since 2005, and its path to statehood was anticipated long before the outcome of the January 2011 referendum. Like many former colonies in Africa, the borders of Sudan were drawn in an arbitrary manner that often ignored fault lines of culture, topography, religion, and ethnicity. Sudan, in the north, is mostly desert terrain and home to majority Arab and Muslim populations as well as the capital city of Khartoum. The South, on the other hand, is landlocked, populated mostly by Christians and followers of traditional spirituality, and contains large forests and swampland. There is little reason for these areas to exist as a single country, aside from the whims of former colonial powers, and this contradiction has resulted in decades of violence and discrimination.

This mutual antagonism did not end with South Sudan being granted formal independence. The South took the majority of the oil producing territory with it, and rebels continue to operate on both sides of the border. And though the two countries are not officially at war, Sudan and South Sudan have conducted several military operations against one another, including arming rebels and seizing oil-producing border territories. There have even been reports of minor Sudanese air raids in the border regions.

Amidst this atmosphere of violence and undeclared war, a bitter oil dispute arose at the end of 2011. Though South Sudan possesses approximately three quarters of the oil of the formerly united Sudan, it has no way of exporting it without using Sudan’s pipelines to the sea. This precarious situation came to a head when Sudan, insisting that South Sudan had failed to pay the necessary fees for oil transportation, began impounding oil shipments. In retaliation, South Sudan shut down oil production in January of this year, starving both countries of their chief source of revenue.

After several months of negotiation, this dispute is now approaching a final settlement. The agreement is still awaiting final security details, but the big ticket issues of fees and finances have already been agreed to. Under this new deal, South Sudan will pay Sudan $9 USD per barrel transported through the latter’s pipelines, in addition to $3 billion US in compensation for revenue lost during the oil stoppage.

Though neither country is fully satisfied with this arrangement, each was willing to compromise their initial position to bring the oil impasse to an end. This accord therefore represents a rare diplomatic success; one that has some observers wondering if it represents a fundamental shift towards peaceful co-existence.

Unfortunately, this arrangement was reached not out of a new sense of friendship but out of dire economic necessity. The oil industry is, by a wide margin, the main source of income for both governments. In the case of South Sudan, it accounts for a staggering 98% of the total government budget. Therefore, ceasing oil production was an incredibly bold move that, if sustained, would have had utterly catastrophic consequences. Some observers were even predicting a complete state collapse if a deal wasn’t reached quickly.

For Sudan, the deal is vindicating. After impounding South Sudan’s oil, they were accused of corruption and simple thievery. With the final agreement’s provision for the South to compensate Sudan for lost revenues, a message is sent that Sudan’s actions weren’t criminal and it was merely a victim in all this. The agreement also provides much-needed stability for the oil trade, which is more critical than ever to Sudan given their heavy reliance on oil fields no longer under Khartoum’s direct control.

For South Sudan, the deal provides a way out of its self-initiated brinkmanship. Though economically suicidal, the stoppage was politically popular in South Sudan, sending as it did a strong message that Africa’s newest country was not going to be bullied. It would have been incredibly difficult for the government of South Sudan to simply renege, as buckling under pressure and appearing weak to constituents and rivals is simply not a viable strategy for a new and relatively unstable government. The oil-halt presented South Sudan with a serious dilemma: they could not back away from the hard line they took without dramatically weakening their internal and external position, but they could not hold the line much longer without destroying their own country.

Therefore, this deal represents both countries stepping away from the brink of disaster for their own sakes and nothing more. It was a situation that quickly spiralled towards disaster, and everyone is glad to have an ‘out.’ While oil politics is one of the biggest obstacles to peace and amiability between Sudan and South Sudan, the partial stability of this deal is not likely to erase decades of enmity, mistrust, and resentment. With each country secretly arming rebels in the other, and with politicians on both sides of the border spouting aggressive rhetoric about destroying the other’s allegedly corrupt government, violence is likely to endure.

Most oil producing territories are located within contested border regions, and skirmishes are set to continue as each country jockeys for control. The oil-production halt nearly ruined South Sudan, so it is unlikely that their government will use that tactic in the future. It was effective in garnering international attention and putting pressure on Sudan, but ultimately proved to be unsustainable. Without the threat of mutual disaster, conventional violence will likely continue along the oil-rich border as politicians capitalize on decades of ethnic, racial, and religious enmities to fuel their fight for the oil fields.