Inflation is the prevailing economic trend of late, fueled by a surge in post-lockdown demand and disruptions in the global supply chain. Food prices are no exception; in fact, the latest reading from the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) food price index hit the eye-watering level of 130 in September (the 100 baseline is a weighted price index based on a basket of 2014-2016 averages). This represents a 1.2% month-on-month increase and a 32.8% increase from the year before.

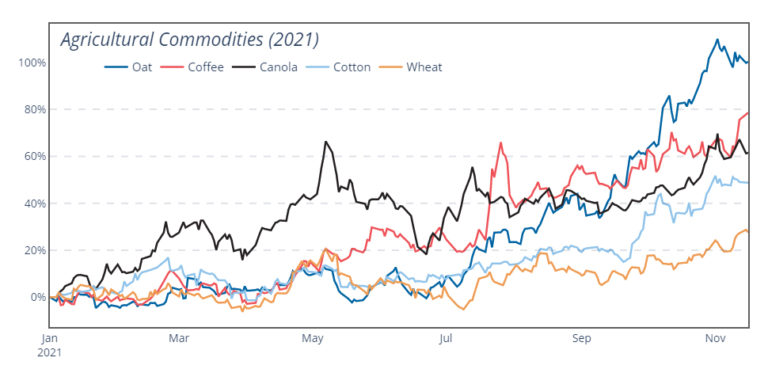

The FAO index breaks down into food types, all of which recorded broad increases through 2021. The vegetable oil price index led the way with a 60% jump from September 2020. Price momentum stems in large part from an ongoing rally in palm oil, which has seen production shortfalls due to migrant labor shortages and pest infestations in Malaysia, the world’s second-largest exporter. Palm alternatives such as rapeseed and soy oil have also seen sustained inflationary momentum through 2021, increasingly so as high oil prices create added incentive to convert the crop into biofuel.

Cereal prices saw the second-biggest price gains, up approximately 27% year-on-year and 2% month-on-month. Wheat and maize led the way at 41% and 38% higher year-on-year, respectively. Price momentum for wheat has been building toward the end of the year, with a 4% increase month-on-month from August. This reflects crop shortfalls across major producers, primarily due to bad weather; for example, Canada (approx. 40% below 2020 output), Russia (13%), and the United States (7%).

Broadly, the causes of food inflation mirror those fueling inflation elsewhere. Producers are unable to ramp up supply swiftly enough to meet surging global demand, with labor shortages inevitably giving way to higher wages (ergo higher production costs). Combine this with a year of disastrous weather events and shipping logjams and the result is a recipe for higher food prices.

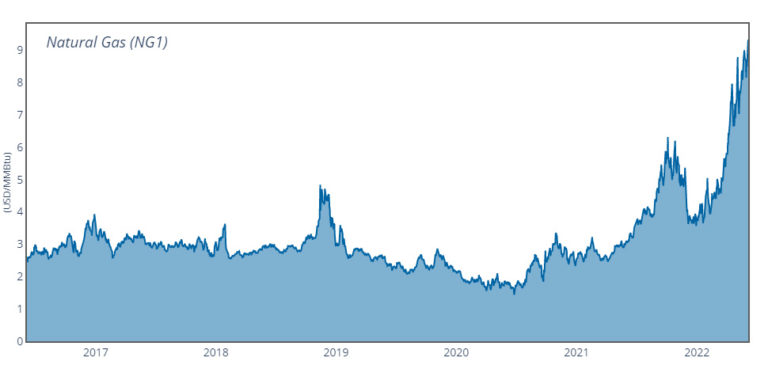

Yet there’s one last ingredient to consider: energy prices. And this is what can lend recent price trends greater momentum heading into 2022, risking greater forex pressures for major importers and even humanitarian crises in vulnerable states. Given the inconclusive result of the latest OPEC+ meeting, oil prices appear set to sustain their recent highs (and energy alternatives are rallying across-the-board). As a result, it’s entirely possible that the present food price crisis will eventually dwarf that of 2010-2012 and reach well into next year.

Net food importers without significant foreign exchange reserves are most at risk to rising food prices. Moreover, COVID-19 has strained fiscal resources around the world, leaving governments with fewer tools to ensure price stability for their populations via temporary subsidies and price controls. Conflict zones with failing or absent governing institutions are most at risk of food insecurity, such as Libya, DRC, Yemen, Syria, South Sudan, and (regions of) Ethiopia. Then comes the larger, import-dependent emerging economies such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, Nigeria, and the Philippines, all of which are still recovering from the economic upheavals of COVID-19.