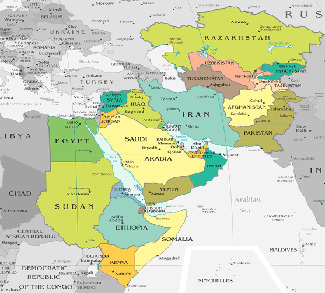

The INSTC as it is imagined is nothing less than a geopolitical game-changer: a 7,200-km trade corridor linking St. Petersburg to Mumbai, one that wires India into the trade circuits of Central Asia and enables Russia to reach new and lucrative markets in the Global South via the Persian Gulf.

For India, the INSTC represents a homegrown alternative to China’s Belt and Road, a new avenue into European markets, a fount of cheap coal and oil from Russia, and an insurance policy should there ever be a falling out with the West. For Russia, it offers an escape from the vice of Western sanctions and a promise of privileged position in the trade flows of tomorrow. For Iran and Azerbaijan, the INSTC is an opportunity to extract developmental and trade concessions from the project’s primary backers. And for the BRICS, the INSTC is a chance to flex the bloc’s muscles by actualizing a project that reroutes trade flows beyond the reach of US sanctions.

This is the vision of the INSTC. The reality, however, is entirely different, as the project has been largely stalled for over 20 years, now requiring significant investments to fill rail gaps and expand terminal capacity in the Caspian Sea legs. Moreover, US sanctions continue to hang like a sword over the project, sapping its momentum.

This backgrounder will assess these risks while examining the interests and regional geopolitics behind the INSTC trade corridor.

The Evolving Geopolitics of the INSTC

The INSTC is not a new vision, having been originally mooted in 2000 and then ratified by India, Iran, and Russia in 2002. It wasn’t long before the original three were joined by other interested parties, including Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Ukraine, Oman, and even Syria – all of which saw value in the INSTC drive to establish a direct trade route between the Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, and the Caspian Sea, and then further into Northern Europe via Russia. From a raw efficiency perspective, the INSTC route represents an attractive alternative to traditional Suez Canal trade flows, with the potential to reduce transit times by up to 40% and freight costs by up to 30%.

Fast-forward nearly 25 years and the INSTC project has still not been realized. This glacial pace is more a consequence of geopolitics than anything else, as the project was and remains a lucrative endeavor for all states involved. The delays mostly trace back to Iran, a founding member and key leg of the trade corridor, which has often been targeted by Western sanctions to the detriment of the INSTC. These include the so-called Axis of Evil-era sanctions, nuclear proliferation-related sanctions, and terrorism-related sanctions dating back to the 1990s, all of which have at various times made it difficult for Indian and Russian companies to operate in Iran.