Summary

Ethiopia has officially informed Egypt that it has commenced the next stage of filling the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), ramping up longstanding tensions between the two countries.

Background

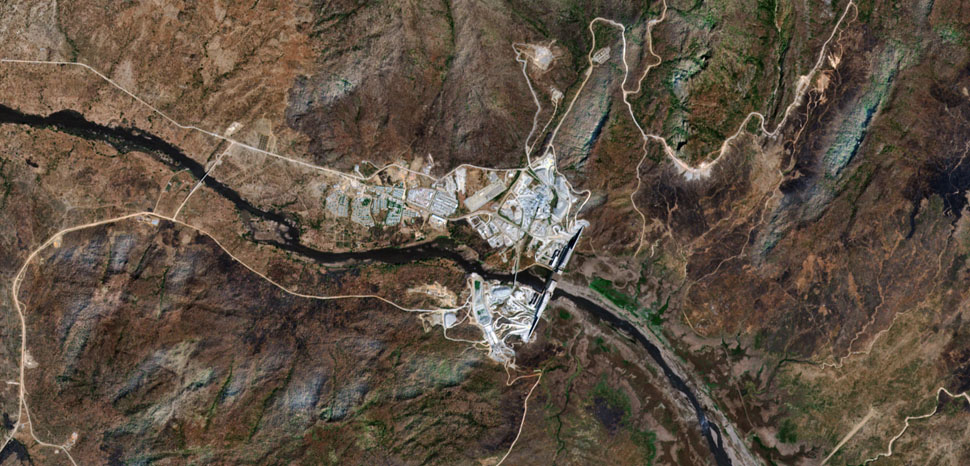

Under construction for over a decade now, GERD represents a colossal public works undertaking. Upon completion, the $4 billion dam will have a reservoir capacity of 74 billion cubic meters, which is well in excess of the 55 billion cubic meters of yearly Nile waters that Egypt is owed under a 1959 treaty with Sudan (Ethiopia was not included in the treaty). The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam will bring new water supplies to an otherwise parched landscape in Ethiopia. It will also generate up to 6,000 megawatts of electricity, making it the largest hydropower facility on the continent.

But Ethiopia’s gains come at the expense of water flow available to downriver states such as Sudan and Egypt, the latter of which is so reliant on the Nile for drinking water and irrigation that it has typically viewed the construction of GERD as an existential national security concern. Egypt is already one of the most water-stressed countries in the world, with decades of population growth and economic development whittling away the once endless bounty of Nile waters. For Egypt, the risk posed by GERD is most acute not during the times of plenty, such as the last few years where above-average rainfall has mitigated the downriver impacts of the GERD’s initial filling process. Rather, it’s during times of water scarcity that geopolitical tensions are most likely to be laid bare, as such times prompt hard decisions in Ethiopia over how much water to keep in the GERD’s reservoir – a choice that can be make-or-break for both downstream countries and the GERD’s electricity output within Ethiopia. Some 2,100 megawatts worth of electricity generation at Egypt’s Aswan Dam would also be at risk during such times.

Though still under construction, the dam now spans the entire width of the Blue Nile near Ethiopia’s border with Sudan. Over the next three years, the dam wall will be raised to allow for more water storage in the reservoir. The reservoir is expected to reach its maximum capacity of 74 billion cubic meters sometime in the next four to six years.

Impact

Notwithstanding the overall slow pace of GERD’s filling and technical questions over whether Addis Ababa could stop the process even if it wanted to, cross-border tensions have resurfaced after Ethiopia notified downriver countries that it has commenced the next stage of the filling process. A nascent anti-GERD coalition has brought together Egypt, a country that enjoyed free reign over Nile waters for hundreds of years, Sudan, which has soured on the project more recently after the filling process upended portions of its water infrastructure last year, and Saudi Arabia, which has recently thrown its diplomatic weight behind a close ally in Cairo.

This coalition cannot realistically hope to stop or reverse GERD becoming operational. Indeed, the dam has become a point of national pride for many Ethiopians, such that it’s no coincidence that the filling process is going forward right on the heels of a disastrous (and far from resolved) conflict in Tigray. What the coalition can hope to accomplish, though, is the hammering out of a binding agreement that would ensure a given amount of flow to downriver states and establish lines of communication and information sharing so as to avoid disruptions like the shock to Sudan’s irrigation systems last year. Success won’t come easy since these issues can devolve into zero-sum games, especially against the backdrop of increasing water scarcity. Ethiopia has thus far only been willing to commit to a set of non-binding guidelines and has favored an AU-led negotiating process that dilutes the joint leverage of Sudan and Egypt.

Until such a time that a final agreement is worked out, there remains a risk of diplomatic and even military posturing by downriver states as they try to secure a favorable long-term deal. This is why the dispute has been referred to the UN Security Council as a matter of international security, with the Council expected to debate the matter on Thursday.