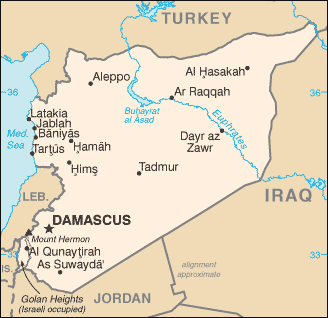

Russia’s decision to greatly reduce its military presence in Syria, coming as it did with little warning, has left the world struggling for explanations. Russia is to maintain a military presence at its naval base in Tartus and at the Khmeymim airbase. In fact Russia is “withdrawing without withdrawing.”

The partial withdrawal is seen by many as a message to the Assad government not to take Russia’s military aid for granted, and to be more flexible in the upcoming peace negotiations.

As Robert F. Kennedy Jr., attorney and nephew of US President John Fitzgerald Kennedy explains, the major reason for the West’s attempt to overthrow the Assad government was to build a natural gas pipeline from Qatar that traversed Syria, capturing its newly discovered offshore reserves, and continuing on through Turkey to the EU, as a major competitor to Russia’s Gazprom.

By re-establishing the Assad government in Syria, and permanently placing its forces at Syrian bases, the Russians have placed an impenetrable obstacle to the development of the Qatar gas pipeline. Russia has also placed itself at the nexus point of other new offshore gas discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean, including Israel, Cyprus, and Greece.

It’s not hard to imagine a new Russian pipeline to Europe serving these new partners. Could easing of sanctions also lead to the implementation of the long-stalled plans of Gazprom for a second pipeline under the Baltic Sea to Germany for Russia and its partners, Royal Dutch Shell, Germany’s E.ON, and Austria’s OMV?

Although the powers involved in Syria are trying to project the partition of Syria as a last resort and a stable political solution that would bring equilibrium, it is not a conclusion reached after all other options were exhausted, which has brought many experts to question whether the partition of Syria was the objective all along.

Below is just one of such options advocated by various geopolitical experts all along, published by Foreign Policy Research Institute in 2013:

The most viable alternative to the violent restoration of Sunni Arab hegemony in Syria is partition – either “hard,” resulting in two or more independent states (e.g. Sudan, 2011), or “soft,” as O’Hanlon proposes, resulting in autonomous centralized cantons under a weak federal government (e.g. Bosnia, 1995).

As in Lebanon during its 1975-1990 civil war, de facto partition is happening every day. The question at hand is whether the international community should encourage a settlement that reifies and institutionalizes this fragmentation, rather than seeking to propel one side or the other to victory.

[Spheres of Influence after Partition in Syria]

Jordan and perhaps Israel would find a friend in a Druze statelet, while a coastal Alawite-dominated statelet would be sure to align with Tehran and Moscow (indeed, partition could be Russia’s best hope of holding onto its naval facility at Tartus long-term). The Kurdish zone would likely form a close relationship with its counterpart in Iraq. The Arab Gulf states would own the center (literally, in many places).

Many of the present conflicts in the world today take place in the former colonial territories that Britain abandoned, exhausted, and impoverished in the years after the Second World War. This disastrous imperial legacy is still highly visible, and it is one of the reasons why the British Empire continues to provoke such harsh debate. If Britain made such a success of its colonies, why are so many in an unholy mess half a century later as major sources of violence and unrest?

British Geopolitics on the Subcontinent

The British policy toward South Asia, and the Middle East as well, is uniformly colonial, and vastly different from that of the United States. Even today, when Washington is powered by people with tunnel vision at best, US policy is not to break up nations, but to control the regime, or, as has become more prevalent in recent years, under the influence of the arrogant neocons, to force regime change. While this often creates a messy situation—for example, in Iraq, Libya, Syria —the U.S. would prefer to avoid such outcomes.

Britain, on the other hand, built its geopolitical vision in the post-colonial days through the creation of a mess, and furthering the mess, to break up a country; exactly on the same lines India was partitioned in 1947. This policy results in a long-drawn process of violent disintegration. That is the process now in display in nations where the British colonial forces had hunted before, and still pull significant strings.

When the British left the Indian subcontinent in 1947, it was divided into India and Pakistan. The British colonial planners, coming out of World War II, realized the importance of controlling the oil and gas fields. If possession could not be maintained, the strategists argued, Britain and its allies must remain at a striking distance, to ensure their control of these raw material reserves, and deny them to others.

Here is where the strategic importance of then British India (India & Pakistan) comes into play, which the historians and political analysts have forgotten.

Strategic Importance of India/Pakistan & the Middle East

Germany surrendered on 5th May 1945. The same day, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered an appraisal of the ‘long-term policy required to safeguard the strategic interests of the British Empire in India and the Indian Ocean’ by the Post-Hostilities Planning Staff of the War Cabinet. And, on 19th May, this top-secret appraisal report was placed before him. The central point of this report was that Britain must retain its military connection with the subcontinent so as to ward off the Soviet Union’s threat to the area.

The report cited four reasons for the strategic importance of India to Britain:

- Its value as a base from which forces located there could be suitably placed for deployment both within the Indian Ocean area and in the Middle East and the Far East.

- A transit point for air and sea communications.

- A large reserve of manpower of good fighting quality.

- From the northwest of which British air power could threaten Soviet military installations.

In each and every subsequent appreciation of the British chiefs of staff from then on until India’s independence that is available for examination, the emphasis was on the need to retain the British military connection with the subcontinent, irrespective of the political and constitutional changes there. Equally, they stressed the special importance of the northwest of India in this context. (Top-secret document, PHP (45) 15 (0) final, 19 May 1945, L/W/S/1/983988 (Oriental and Indian Collection, British Library, London).

The achievement of these objectives was collectively called the Great Game. With the beginning of the eighteenth century, the French were also able to figure out India’s importance and actively tried to be part of the process of having India’s resources shared for their political objectives in Europe. This reached the pinnacle with the Napoleonic Era where Napoleon was able to figure out that as long as India was in the hands of British it would be impossible to checkmate British in continental European wars. So the Grande army moved into Russia with a tacit agreement of taking India via land route through Afghanistan. When British sensed this plan, coalition after coalition against French were set up finally ending in a war between France and Russia in which Napoleon was finally weakened.

Later, Russians were able to figure out this land route and its benefits and swiftly moved into southern Khanites (Shia kingdoms like Tazakisthan, Azerbaijan etc) occupying them one after the other. The British, sensing the danger of Russian incursion or outright occupation of India, did three things:

- Created buffer kingdoms post 1857 in the form of Kashmir, Afghanistan, and Sikh Federated states.

- Trained the British Indian Army in the General Staff techniques as envisioned by German strategists like von Moltke and others.

- Meddled with the cultural heritage of India.

The social engineering was in such a way that in 100 years Indians lost everything of their glorious traditions – culture, customs, sciences – thinking that they have nothing to do with them and meekly surrendered to the British and their system of education.

To achieve the total control of India, the British used the Divide and Rule policy in terms of religion, clan, tribe, caste, region and language; the effects of which we are still felling as a continuous descent into mental, emotional and psychological slavery from which Indians were never able to come out. This is exactly what is playing out in the Levant today. This same strategy continues, disguised under various names and terms – the New Great Game, Cold War, New Cold War, etc.

Just how many countries were divided even after the end of World War II in the name of ‘balance of power’ into various ‘spheres of influence’? When the borders were drawn, the conflicts were drawn with them and it is called a ‘peace plan.’ Just like Syria now, even India was partitioned by the British in 1947; how much peace has that brought to the two countries? Why do India and Pakistan blame each other and interestingly are unaware or never acknowledge the strategic reasons for which it was divided by the British? Most importantly, after more than six decades of Independence, why should the former colonies accept the British drawn borders which has only brought more destruction?