When Russia annexed Crimea and waged a hybrid war against Ukraine in Donbas in 2014, renowned realist scholar John Mearhseimer argued that the Western arrogance emanating from the U.S. dominance in the so-called liberal world order was to blame for the Russian aggressiveness. Accordingly, it was the West’s expansion toward Russian borders through NATO/EU enlargements and democracy promotion that triggered an unavoidable zero-sum game over Ukraine and accelerated the unravelling of the European security system built after the end of the Cold War. In Mearsheimer’s (theoretical) world, small powers such as Ukraine do not have a right to join the alliance of their choosing if this geopolitical choice is perceived as a hostile move by the neighboring great power. Thus, it should come as no surprise that he is often notoriously depicted as a Russlandversteher (“Russia understander”) or Putin apologist in Western media outlets.

Recent deterioration of the security situation in and around Ukraine once again turned the spotlight on Russia’s aggressive behavior and led some observers to the Mearhseimerian conclusion that Russia was being reactive, not proactive, in the face of new threats posed by Ukraine and its Western partners. As US-Russia relations have now hit a post-Cold War nadir and Ukraine actively seeks NATO membership, the Kremlin seems poised to use everything in its geopolitical toolbox to strengthen its hand to the detriment of the Western powers. As in 2014, Moscow is employing hardball tactics vis-à-vis Kyiv, mainly by concentrating large numbers of troops near the borders to demonstrate the lengths to which Moscow is willing to go to undermine Ukraine’s pro-Western assertiveness.

Proactive vs reactive

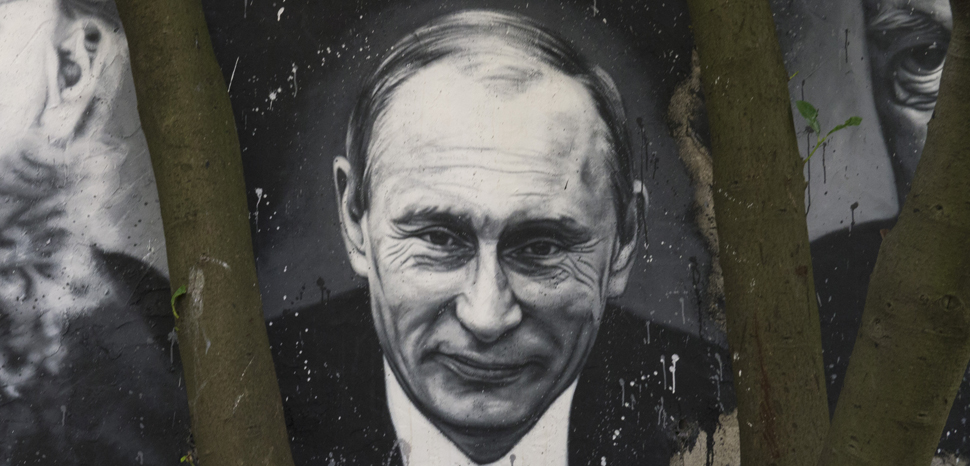

The proactive approach to Russian behavior subscribes to a notion that the sources of Russia’s conduct in Ukraine-like situations are essentially domestic, and it is Vladimir Putin’s diversionary war incentives that drive the Kremlin’s aggressive rhetoric. In this context, the regime’s concerns about the large-scale protests after the poisoning and then arrest of the opposition leader Alexei Navalny is seen as a contributing factor to Russia’s increasing belligerence. At the same time, Moscow might entertain the idea of replicating the ‘Saakashvili scenario’ by staging a limited military maneuver aimed at ‘repelling’ a false flag attack from Ukraine to bolster the regime’s domestic popularity before the parliamentary elections in autumn. According to the public opinion surveys conducted by Levada Center, President Putin’s approval rating saw an all-time low (59%) as the coronavirus pandemic badly hit the Russian economy in 2020. That said, a new successfully-orchestrated military operation in Ukraine with heavy media coverage would boost Putin’s image and regime security, at least in the foreseeable future.

Moreover, some observers link Putin’s decision to raise the stakes in Donbas to his foreign ambitions to proactively change the nature of Normandy talks and strengthen Russia’s negotiating position vis-à-vis Ukraine, Germany, and France. The implementation of the Minsk Agreements (Minsk-2) along the lines offered by Russia would give the separatists in Donbass a special status within Ukraine and hence provide Russia with a mechanism for curbing Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations once and for all. Moscow might even go a step further and use the escalation around the borders as a pretext to deploy peacekeepers or upgrade diplomatic relations with the de facto entities it sponsors in eastern Ukraine. Last but not the least, the Kremlin might also be interested in testing the Biden administration’s resolve to defend Ukraine in time of crisis. As bilateral tensions are reaching new highs in the wake of new US sanctions (Nord Stream 2, SolarWinds) on Russia, further escalation in Ukraine would be a new challenge for the Biden team, which is yet to craft its strategy toward Russia.

Ironically, even if Mearsheimerian (offensive) realism expects great powers to maximize benefits at the expense of smaller ones, in the case of Russian sabre-rattling in the common neighborhood, the proponents of this view shift the emphasis to Russia’s legitimate ‘rights’ to safeguard its national interests in its ‘near abroad.’ For example, referring to Robert Jervis’s seminal work on perception in international affairs, Stephen Walt – a prominent neorealist – proffered a similar view back in 2015 that Russia’s aggressive reaction to the events in Ukraine was “primarily motivated by fear and insecurity” and therefore, “arming Kyiv is a really, really, bad idea.” With the same logic, the taproot of the current escalation along the Ukrainian borders must be seen as Moscow’s response to Kyiv’s alleged attempts to de facto reintegrate Donbass and Crimea by use of force and Western countries’ support to Ukraine in this regard. Interestingly, some observers may not agree with this kind of interpretation of events in Ukraine, but Russia’s political establishment seems to believe it sincerely. In Mearsheimer’s world, uncertainty about the opponent’s intentions may push the Russian leadership to amass tens of thousands of troops near Ukraine to preempt an attack no one in Ukraine has been planning.

According to Dmitry Trenin, the Director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, “it was Ukraine who moved first.” Zelensky’s order to ban broadcasting of three pro-Russian TV channels and move additional forces and heavy weapons close to the line of contact in Donbas were enough to provoke the Russian reaction. Besides the domestic rally-around-the-flag effect in time of economic difficulties, Ukrainian assertiveness was supposed to garner the West’s support vis-à-vis an unruly neighbor to the east and present Ukraine as a bastion standing in the way of Russia’s further advance toward Europe. While the U.S was adamant in supporting Ukraine, Germany and France issued a statement “calling on all sides to show restraint and to work towards the immediate de-escalation of tensions.” On its side, Moscow made it clear that it would not stand idly by while Ukraine was preparing for a military offensive in the region. As later developments showed, the Kremlin was keen on retaining escalation dominance.

Ukraine’s NATO membership is a red line for Moscow and Zelensky’s actions in this regard might not bode well for an already brewing instability in the east of the country. His 6 April claim that “NATO is the only way to end the war in Donbas” and a membership action plan (MAP) would deter further escalation between Russia and Ukraine, once again reinforced the realist proposition that trying to militarily deter Russia in such kinds of situations would make the Kremlin even more aggressive, triggering an action-reaction spiral of growing hostility. This is what actually happened after Zelensky’s speech as Russia started to concentrate a large number of troops along the border. Reacting to the Western politicians’ support of Ukraine Russian leaders accused NATO, the EU, and the U.S. of “deliberately turning Ukraine into a powder keg by ramping military assistance.” The Russian defense minister claimed that troop deployments aimed at nothing more than responding to NATO activities that threaten Russia.

In search of a “way out”

Mearsheimerian realism sees Ukraine’s future as a stable and prosperous state in its being a “neutral buffer” between multiple power poles, akin to Austria’s position during the Cold War. Accordingly, Russia is still a declining power with a one-dimensional economy and need not be contained. The Western countries should abandon NATO’s further enlargement toward the post-Soviet space and engage Russia to build a stable and prosperous neighborhood. At the same time, avoiding a clash with Russia in Ukraine would unleash a potential to cooperate in other policy areas ranging from climate change to arms control. Neither Russia nor the West/Ukraine will benefit from tensions boiling over around Donbass and Crimea.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com