Of all current NATO members, Türkiye probably has the closest relations with both Kyiv and Moscow, as indicated both by the grain export deal negotiated in 2022 as well as Erdogan’s public praise and support for Putin while simultaneously supplying drones to Ukraine.

Türkiye has also flexed its muscles in the diplomatic front, negotiating a resumption in relations with Ethiopia and Somalia in late 2024. With talk in Europe of sending peacekeepers to Ukraine as part of a negotiated peace deal, the question of who exactly would lead and man the peacekeeping force looms large.

Yet here, one country, Türkiye, stands out from the rest. Alongside its ties with Ukraine and Moscow, Türkiye possess NATO’s second largest active-duty military at around 350,000 personnel, behind only the United States, some of which in theory could be provided to lead a peacekeeping force. Though there are no guarantees that such a peacekeeping operation will come to pass, Türkiye’s diplomatic overtures signal a willingness to engage in more theaters besides the ones it’s already involved in, namely the Middle East, Caucasus, and Central Asia.

Various components of a peace plan have been floated at different points; for example, in the then president-elect Trump’s proposal for a ceasefire, which was rejected on December 30, 2024 by Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov. Lavrov’s objections were two-fold: that Russia could not accept Ukraine in NATO, even with a 20-year delay, and that a peacekeeping force composed of Western states would likewise be unacceptable.

Addressing the latter concern is an easier one to tackle. Typically, in order to be successful, peacekeepers need the trust of all or most parties to be effective. That means that a European or NATO-led peacekeeping force is in all likelihood off the table, as Lavrov indicated.

But what if peacekeepers from some other countries were involved? Traditionally, UN peacekeepers have been dominated by soldiers from South Asian nations; four of the top five nations in terms of peacekeepers contributing to UN missions are found in South Asia. And although it is not a strict necessity, there often exists a bias in favor of peacekeepers that have a similar cultural understanding to the parties they are keeping the peace in favor for. This is why in many cases the UN has backed peacekeeping activities by entities like the African Union to in essence police their own backyard. Since 2000, 38 peacekeeping missions in Africa were led by African countries, 22 of them under the direct auspices of the African Union.

The Ukraine war, outside of the North Korean presence in Kursk at the time of this writing, is fundamentally a war between, and a war affecting European states. Because Russian President Valdimir Putin has portrayed NATO and its 30 European member states as essentially at war with Russia, this limits the options of a regional partner trusted by both sides. Notable European countries that are officially neutral include Serbia, Austria, and Ireland, but together, these three countries have a combined population of only about 21 million and 55,000 active-duty soldiers.

Going off of the figures for Cyprus’ “green line” DMZ, a typical estimate for peacekeepers per kilometer of front is around 10-20. The border between Belarus and Ukraine as well as Russia and Ukraine together comprise a little more than 2000 km in total length. At a conservative estimate then, about 40,000 peacekeepers would be needed to secure the entire stretch of the border. In contrast, the largest UN peacekeeping mission deployed stood at around 20,000 peacekeepers in the DRC at its peak.

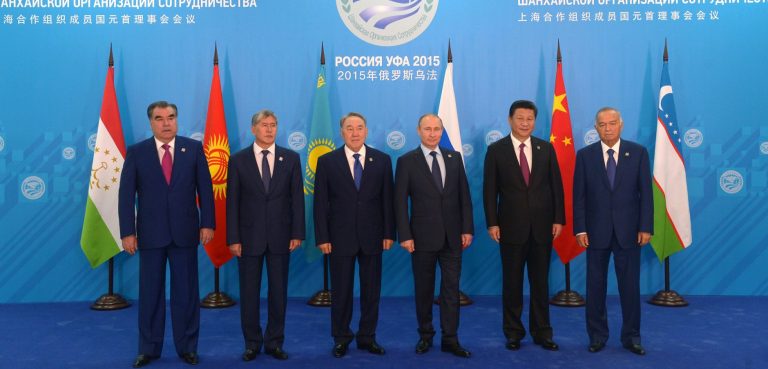

In addition to the logistical demands of maintaining such a large presence in the border region, Türkiye may also wish to look towards other states in supporting its peacekeeping efforts. Culturally speaking, the nearest countries to Europe that could effectively support a peacekeeping mission are in the former Soviet republics. Of these ex-Soviet-states, the only ones with a military worth fielding are Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. Aside from Ukraine, all the other ex-Soviet republics are small in both population and active military personnel. All four of these countries are also members of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), and all are in NATO’s Partnership for Peace.

The three smaller states are all officially neutral in the conflict. Yet with these four together, totaling 530,000 active military personnel, this may still not be enough not to avoid undue strain on the militaries involved with the estimated number of troops needed. If Türkiye were to lead this quasi-European peacekeeping force in Ukraine, it could do well to get more of those neutral countries mentioned earlier on board.

Any peacekeeping effort would be difficult to implement regardless of who leads it. Peacekeepers would be put in harm’s way, especially if geopolitical tensions remain high. Any peacekeeping mission will need to have a clearly defined mandate agreed to by both parties. Coordination between any multinational force must be meticulously planned. Finally, the size of the peacekeeping force could end up costing significant financial resources, which must come from somewhere.

Overall, the main benefits to staging such a multinational force would be the increased legitimacy of the operation in the eyes of the international community as well as burden sharing among participating nations. Importantly, it follows in the precedent of deploying multinational forces into conflict zones using intra-regional troops as the basis for the operation. Thus, the main challenges to this proposal come not from its theoretical composition, but from the challenges inherent to setting up a peacekeeping force to begin with.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.