Warnings of a deteriorating political and security situation in Iraq were plentiful over the past year, driven by a civilian death count climbing towards 2008 levels and militant groups gaining an urban foothold in the cities of Fallujah and Ramadi. Even the fall of Mosul, as spontaneous as it may seem, had a build-up of several days as militants accumulated in areas surrounding the city.

It isn’t terribly surprising that these warnings ended up falling on deaf ears given the steady stream of bad news that has flowed from the region over the years. But last week’s events should put an end to all that. Now it’s painfully clear that the situation has changed and civil war has broken out in Iraq.

The ISIS offensive is a game-changer

Regardless of whether or not the Iraqi army succeeds in pushing militants from the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) back, the fall of Mosul and much of central Iraq is a game-changer for several reasons.

The offensive represents a propaganda coup of the highest order for ISIS, and it comes right as the group’s Syria fortunes were on the decline. The rapid fall of Mosul, which took a mere 1,200 fighters just hours to seize a city of millions, suggests a high degree of tactical competency for ISIS, which will doubtlessly reflect in the group’s ability to recruit from Iraq’s disaffected Sunni community. ISIS also received a boost on the equipment front when tanks, Humvees, helicopters, and countless US-provided weapons were abandoned by fleeing government troops.

Just as ISIS has been presented in a dangerous and capable light, the Iraqi government has been made to look foolish, ineffective, and hopelessly weak. The dramatic and embarrassing accounts of Iraqi troops throwing down weapons and tearing off uniforms in their haste to escape are deleterious for state authority in Baghdad. By calling into question the fundamental role of government – to protect its citizens – these events have transformed what was once a political question for Iraq’s Sunni population into an existential one. And wherever they turn for security in the future, whether ISIS, tribal militias, or other paramilitary groups, it will inevitably be delineated on strict sectarian lines.

Sectarian fault lines are deepening

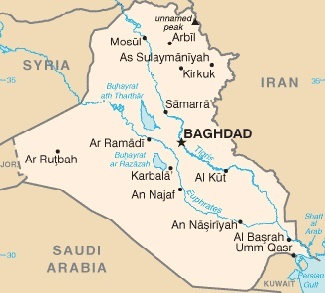

Although Iraqis have suffered terribly from a slow burn of sectarian violence over the past decade, we are now seeing an increased trend for communities to coalesce around armed groups in opposition to the state. The Kurds seemed to have a plan in place from the moment the violence broke out, and that was to consolidate their own long-term position in the quest for autonomy and eventually statehood. The peshmerga (the armed forces of the Kurdish autonomous region) are arguably the most capable fighting force in Iraq at present, and had they engaged ISIS head-on over Mosul, events would have turned out very differently. But they did no such thing, opting instead for a passive approach in order to focus their efforts on the bigger prize: Kirkuk. When peshmerga moved in to secure Kirkuk, it was not to shield their Arab brethren from the ISIS onslaught, but rather to establish Kurdish control over an oil-rich city that has long been contested by both Erbil and Baghdad. With the Iraqi army nowhere to be found and a long-promised referendum on Kirkuk’s status on permanent hiatus, it stands to reason that the Kurdish flag might be flying over the city for an extended period.

It wasn’t just incompetence on the part of the Iraqi armed forces that allowed ISIS forces to seize so much territory in northern and central Iraq. The militant group was actively helped by Ba’athist elements from the Saddam-era Iraqi army, and at the very least it got passive assistance from certain Sunni tribal militias (of whose cooperation was crucial to the success of the Anbar Awakening).

On the Shiite side, several sectarian militias are being re-organized to deal with the new threat, such as the Asaib ahl al-Haq and Muqtada al-Sadr’s “Peace Brigades.” Iraq’s highest-ranking Shiite cleric, Ayatollah Ali Sistani, has also issued a fatwa against the ISIS offensive, which, though addressed to “all Iraqis,” will almost exclusively be heeded by Shiite members of the population.

A geopolitical outlook muddied by questions of ideology vs. stability

That Iraq is fracturing is plain for governments worldwide to see. President Obama has dispatched the aircraft carrier George HW Bush to the Persian Gulf in a move widely seen as a precursor to military strikes within Iraq and possibly even Syria as well (keep in mind that the Iraq-Syria border is very porous in parts).

There is some truth to the Obama administration’s assertion that any military response is ultimately futile if it doesn’t go hand-in-hand with political reforms aimed at fostering reconciliation between Iraq’s sectarian groups. However, President Obama is already on the defensive in the domestic arena, which could well compromise his ability to drive a hard bargain with al-Maliki. Though the original decision to invade Iraq belongs to his predecessor, the complete pullout without any permanent US deployment occurred under Obama’s watch. Some of the president’s critics are arguing that this was a strategic oversight which failed to properly safeguard US sacrifices in the name of Iraqi democracy.

Whether we see true pressure from Obama or not, the prospects for genuine political reform in Iraq are bleak as long as al-Maliki remains in power. His heavy-handed governing style has alienated Sunnis and Kurds beyond the possibility of reconciliation, evident in the simple fact that Ba’athists are now throwing their lot in with the most ruthless strain of jihadist ideology in order to effect regime change in Baghdad. Al-Maliki could extend an olive branch before this is all over, but it’s doubtful anyone will be on the other side to accept it.

The original invasion of Iraq raised quite a few eyebrows back in 2003 as pundits speculated that democracy would allow the country’s long-suffering Shiite population to monopolize power, effectively gifting Iran with a regional ally where a nemesis once stood. History has vindicated their skepticism, and the United States now shares a common interest with its long-time enemy: both want to ensure that Iraq doesn’t descend into anarchy. Though Washington and Tehran aren’t in direct contact over the crisis yet, there are rumblings that talks are being considered by the Obama administration. Such a dialogue would confirm what many have known all along – that Iranian cooperation is key to a stable Iraq – and if successful they may even contribute to the wider détente of ongoing nuclear negotiations.

Alternatively if they fail they might take President Obama’s legacy with them.

What to expect in the days to come

Baghdad will not fall. The Iraqi capital is a different beast entirely from the cities overrun by the ISIS offensive. However, a spike in terrorist attacks in the capital is likely.

The Iraqi Kurds will try to remain neutral as long as possible. The authorities in Erbil prefer to remain on the sidelines, consolidate their hold on Kirkuk, and maintain stability in the Kurdish autonomous region – stability that will be tested by refugee flows.

The civil war will be fought in central Iraq. With Iran and the United States firmly behind the authorities in Baghdad, an ISIS push into the Shiite heartland of the south is impossible. That leaves Sunni-dominated central Iraq as the war’s likely battleground, an ideal place for ISIS to switch to guerrilla tactics when faced with the inevitable government counterattack.

There is a grave risk of violence spiraling out of control. With many Sunnis in central Iraq already skeptical about the central government’s intentions, it will be a colossal challenge for al-Maliki to conduct an effective counterattack that doesn’t serve to perpetuate sectarian conflict over the long run. This was also a concern during the height of sectarian violence from 2006-2007; but back then there was at least the hope of a representative democratic state – as well over 150,000 US troops – to coax violence levels down. After eight years of al-Maliki rule, the hope of a democratic state has become a hard sell to many of Iraq’s Sunnis.