Despite their relative infancy, the universe of digital currencies is already increasingly plural and complex as the natural result of divergent evolution. Regarding their governance structures, the spectrum of these high-tech monetary items now includes not just decentralized stateless cryptocurrencies and corporate ‘stablecoins’, but also central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), known as ‘govcoins’. Designed as a new generation of official legal tender powered by blockchain, they showcase the strategic ability of the state to embrace transformative technological innovations whose instrumental applications are useful for the sovereign pursuit of national interests. Whereas many countries —including both great powers and developing nations— are still deliberating about the pros and cons of CBDCs (often in Byzantine-like unconclusive discussions), China has achieved a ‘great leap forward’ with the creation of the e-yuan (e-CNY) as an experimental CBDC. Such breakthrough is not surprising considering factors like the historical role of China as a civilizational state that has been a prolific cradle of inventions (paper money, the compass, gunpowder) and the success of its neo-mercantilist policies in fostering techno-industrial development.

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) started working on blueprints for the development of a centralized digital currency strategy since 2014. Originally conceived as a digital currency / electronic systems (DCEP) project, the e-CNY was introduced as a pilot back in 2019. According to the project’s official white paper, the e-CNY was created primarily as a domestic retail CBDC for everyday payments, but said document also indicates a strong willingness to explore gateways for its internationalization in a foreseeable future. Although there are no official figures about the dimensions of its adoption, statements made by the PBOC indicate that there are 261 million wallets. Shenzhen, Suzhou, Chengdu and Xiong’an —large modern cities which embody China’s rising economic profile— were chosen as the first testing grounds and since then, such exercise has been gradually expanded to other metropolitan areas, most of which are located in wealthy coastal regions. However, a full-scale nationwide launch is still waiting to happen. There will be more clarity for the decision-making process once the results of ongoing trials can be fully measured and assessed.

The e-CNY is no ordinary CBDC for several reasons. China represents the world’s second largest GDP, only below the United States. The ‘Middle Kingdom’ is ahead of everybody else in the transition toward cashless economies and the pioneering development of vast FinTech ecosystems which agglutinate platforms like Alipay, WeChat Pay and UnionPay. According to SWIFT, the renminbi (RMB) is now the fourth most active currency for global payments by value, ahead of the Japanese yen and the Canadian dollar. Moreover, Beijing is an assertive geopolitical player that seeks to overtake ‘Pax Americana’ in order to become the leading pillar of tomorrow’s world order in a multipolar setting. At this point, it is still unknown if the grandiose promise of this ‘Chinese dream’ will ever be realized. Nevertheless, in the arena of global geopolitics, China’s ascending strategic trajectory brings risks and opportunities for other states. Considering these factors, it is pertinent to rely on the lens of strategic foresight to examine the prospective ramifications of the e-CNY for Chinese national power, geoeconomic rivalries, and the fate of hegemony.

Implications for China’s National Power

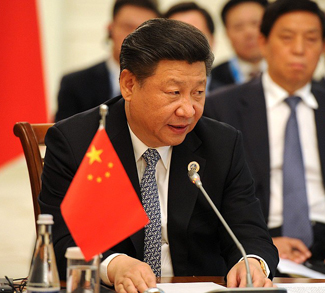

The design and rollout of the e-yuan needs to be understood not just as a novel innovation. This project must be framed in the context of China’s “national rejuvenation” efforts, a mission that seeks to fulfil the historical aspiration to restore the greatness of the ‘Middle Kingdom’ as a powerful and prosperous state whose hierarchical status commands the respect and admiration of the known world. Tellingly, President Xi Jinping himself has emphasized the importance that Beijing invests in groundbreaking steps to get ahead in the endeavor of unlocking the full potential of blockchain as a transformative technological invention. Furthermore, considering the role of China as the world’s leading practitioner of economic statecraft, the e-CNY will likely be intensively harnessed to nourish the power of the state. The e-yuan would enable the PBOC to implement a smart monetary policy that can be tailored as a programmable instrument to serve national interests related to the strategic management of trade, taxation and debts. In turn, the proliferation of its circulation at home —and perhaps also eventually abroad— would confer a pervasive ability to collect real-time actionable financial intelligence (FININT) through network panopticons. The surveillance of all transactions based on AI-powered algorithmic cross-referencing systems and big data analytics has the power to detect patterns of suspicious behaviors and to track designated persons of interest such as individuals associated with terrorist, criminal, subversive, dissident, or separatist groups.

Another remarkable feature of this CBDC is that —unlike supranational corporate ‘stablecoins and stateless cryptocurrencies— it is underpinned by the ideological force of nationalism. This underlying ideological subtext demonstrates that, far from being old-fashioned or even backwards, nationalism can flourish in the digital era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The e-CNY is high-tech symbol that carries the image of China’s condition as a state at the forefront in the domain of FinTech ecosystems. Therefore, its take-off has the potential to strengthen the national morale of the Chinese people at home and the projection of Chinese ‘soft power’ overseas. As is known in the political economy of money, the status of a currency is a reputational mirror that reflects the power, wealth and prestige of the state responsible for its issuance.

In general, Chinese policymakers and other members of the country’s strategic community —including scholars, experts and commentators— are soberly aware of the e-CNY’s potential and limits. The idea that the e-CNY represents a proverbial silver bullet with the strength to accelerate the international rise of the renminbi in a meteoric way overnight is grossly out of touch with reality. It is much likelier that this digital monetary unit will play a pivotal role in the incremental ‘long march’ of RMB internationalization in various ways, especially as the digitalization of macro and retail economic exchanges thrive through e-trade. As a vector of financial and monetary interconnectedness aligned with the Middle Kingdom’s ‘digital silk road’, the e-CNY can participate Chinese-led flagship geoeconomic projects such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS). While these structures could conform to the skeleton of Beijing’s rising parallel international economic order, the e-CNY would flow as its lifeblood. Another foreseeable vehicle is the involvement of the e-CNY in loans and development assistance granted to Chinese economic partners in Asia, the Middle East, Latin America and Africa. In addition, the Chinese Currency Institute (which belongs to the PBOC) is collaborating with the Swiss-based Bank of International Settlements in the exploratory development of an operational multi-CDBC bridge (mBridge) project. If successful, this financial infrastructure prototype conceived to support interoperability in cross-border payments can act as a corridor so that the e-CNY can increase its international footprint. In turn, the condition of Hong Kong as a world-class offshore financial service platform is a potential highway worth leveraging for the same purpose. Finally, the growing international connections and market power of Chinese FinTech payments platforms can galvanize the functional ability and the commercial willingness to rely on the e-CNY’s accompanying financial infrastructure for cross-border transactions.

In a nutshell, the e-CNY and the mobilization of Chinese national power will likely support each other in a synergic bidirectional manner. Yet, the international expansion of e-CNY usage should not be taken for granted. Such a process would need to overcome —with ingredients like diplomacy, leadership and consensus— cumbersome political, regulatory, technical and jurisdictional issues and to harmonize heterogeneous interests in a mutually beneficial way. This undertaking seems exceedingly difficult in a global landscape in which turmoil is heading toward a critical boiling point in key areas of the Eurasian landmass, such as the post-Soviet space and the Greater Middle East. Whether it wants it or not, the ‘Middle Kingdom’ may have to face the uncertainty of a new ‘warring states’ period.

The Prospective Involvement of the e-CNY in Geoeconomic Rivalries

From the perspective of Chinese economic statecraft, a strong international presence of the e-CNY would confer both offensive and defensive advantages. Domestically, the experimental launch of the e-CNY project was accelerated by an interest in the development of alternatives that could keep at bay the potential encroachment of cryptocurrencies (like Bitcoin) or private supranational ‘stablecoins’ designed by foreign companies from strategic competitors (like Facebook’s Libra). These unwelcome currencies are viewed by the Chinese ruling elite with deep distrust —if not outright hostility— because their proliferation in mainland China may encourage systemic distortions and weaken Westphalian monetary sovereignty as a quintessential component of statehood. Unsurprisingly, Chinese authorities have gone to great lengths (including draconian measures) to suppress them.

The supporting international platforms, systems and networks through which the e-CNY is expected to fuel economic exchanges could be weaponized in acts of economic warfare against states that assume a confrontational position towards Beijing’s national interests, especially if there is a high degree of reliance on the Chinese CBDC. Through hidden backdoors, the Chinese government might have the ability to pull covert triggers designed to unleash consequential disruptions. Furthermore, the development of a financial ecosystem with a sovereign CBDC as its cornerstone would operate as a resilient protective barrier to shield China —to a certain extent— from the threat of Western coercive sanctions, mitigating their domestic and international impacts. Moreover, with the e-CNY as an expansive spearhead, China would have a leading edge in strategic competition over the conquest of FinTech markets across the Global South if it offers convenient benefits for users such as businesses, investors, and individuals. Finally, as the United States has leveraged the dollar and US-led financial arteries as weapons of choice against enemies, embracing the e-CNY may be helpful to compensate the vulnerabilities of states potentially targeted with such measures as a lifeline that preserves a reasonable degree of access to international economic exchanges and capital markets. In a nutshell, the e-CNY represents a versatile strategic asset for both China and its close strategic partners under adversarial circumstances.

In turn, the emergence of the e-CNY is regarded as a confrontational threat in the strategic communities of the so-called ‘collective West,’ particularly in countries that belong to the US-led alliance of English-speaking maritime powers known as the ‘Five Eyes’. For example, the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs has simulated scenarios in which the e-CNY —as a geoeconomic game-changer— could facilitate China’s control over regions of the Asia-Pacific rimland. The exercise carried out by this research center also explored the possibility that North Korea might rely on the financial infrastructure that undergirds the e-CNY in order to bolster its conventional military capabilities and to bankroll its nuclear weapons program. In a context of simmering strategic competition, British historian Niall Ferguson has encouraged Western states to prevent China from “minting the money of the future.” The British think tank Policy Exchange and the Australian Lowy Institute advocate measures tailored to counter the expansion of Chinese financial architectures in the Indo-Pacific —including the Chinese CBDC— and beyond because they are seen through the prism of systemic rivalries. Even before the release of the e-CNY, Western intelligence services had been studying the strategic implications of the RMB’s growing international acceptance for interstate competition. These strategic anxieties reveal fears about challenges for the US dollar supremacy as dominant reserve currency, the ultimate effectiveness of collective sanctions as a tool of foreign policy, and the primacy of Western nerve centers in international finance.

As the prospect of broad multilateral solutions vanishes due to major power rivalries, intensifying monetary competition, and even the spectre of war, the rise of the e-CNY will be predictably resisted by the United States. Considering certain precedents (like the membership of many NATO states in the AIIB), the possibility that some US allies might partially sign up as e-CNY users to gain a bridge to the handsome profits of business with China remains latent. If a chain reaction is ignited with monetary incentives, states under US strategic tutelage may be tempted to shift toward a policy of either hedging or counterbalancing. From Beijing’s viewpoint, carrots could be more useful than sticks to start dismantling the structure of Washington’s global alliances.

The e-CNY as a Hypothetical Hegemonic Watershed

Supported by the weight of China’s national power, the yuan has made gradual inroads in its journey towards internationalization, including its inclusion in the Special Drawing Rights basket, its status as a minor reserve currency, and its emerging market share in cross-border transactions. In this regard, the e-CNY can hasten this process but by itself it will not lead to the coveted status of major reserve currency. This CBDC would have to muster a lot of firepower to challenge the US dollar’s hegemony. First, the e-CNY would have to gain footholds in China’s immediate periphery and then its sphere of influence would have to encompass a sizeable portion of the Asia-Pacific region before it can realistically aspire to global dominance. The eventual establishment of systemic connections between the e-CNY and hard assets like gold, highly tradeable financial instruments (like bonds or stock), and global markets of strategic commodities such as oil could further the advance of RMB internationalization to commanding heights. There are early signs that may point in such a direction. For example, last year, PetroChina (a state-owned company involved in oil and gas and one of Asia’s largest energy producers) participated in the first crude oil international transaction settled in e-CNY, an operation carried out through the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange. The record of world history suggests that, even if China becomes the world’s top economic superpower in a matter of decades, the official elevation of the renminbi to the summit of the monetary universe as the ultimate ‘coin of the realm’ will have to wait for a while. Although said role confers ‘exorbitant privileges,’ it also comes with risks, costs and responsibilities which cannot be overlooked.

Driven by a revival of its imperial tradition, China is making a bid for to reposition itself as the hegemonic overlord of a multipolar system. Based on the teachings found in their classical schools of strategic thought, the Chinese want to win, preferably without fighting. Beijing does not want to take over the world through direct military conquest (the Chinese believe that such foolish course of action invariably leads to overstretch), even though it is raising preparedness to rely on hard power if necessary in case the critical red lines of its national security are crossed. As analysts like Parag Khanna and David Goldman have argued, the Middle Kingdom’s grand strategy seeks to build an axial core from which a vast network of interwoven Chinese-led platforms which undergird complex interdependence emanate to the four corners of the Earth. In accordance with this model, Beijing’s gravitational pull will be strong enough to voluntarily attract, gather, and assimilate dozens of tributary states. The calculation is that the resulting strength of such scheme will give China the chance to claim the ‘mandate of heaven’ to rewrite the global correlation of forces as a rule-maker, settle scores, and perhaps even to checkmate the United States. China seems committed to raise as the first amongst equals in the concert of great power politics.

Therefore, the e-CNY represents a vector with the potential critical mass to propel de-dollarization on a global scale, facilitate a hegemonic transition, and expedite the architectural renewal of international systems of financial and monetary governance in accordance with Chinese interests. The materialization of these game-changers would remake the structure of polarity within the international system, either through a tense bifurcation or a negotiated compromise similar to what Bretton Woods accomplished after the chaos of World War Two. An e-CNY that operates as sound and reliable international money —i.e. the coin of the realm— would underwrite the Chinese vision of world order (tianxia). Specifically, the growing penetration of the e-CNY in foreign economies with symbiotic ties to China could be hypothetically blandished to encourage alignment, acquiescence, or subordination to Beijing’s foreign policy.

Lessons Learned

Fate does not lack a sense of irony. Although cryptocurrency was originally invented to bypass or override the power of the state, the concept of digital money has been appropriated by national states to enhance their competitive performance in the chessboard of power politics. Although stateless cryptocurrencies and corporate crypto-assets do have meaningful strategic implications for national security, statecraft, conflicts, rivalries and geopolitics, CBDCs —especially those developed by great powers— are even better positioned to assume a greater, savvier and more consequential role in such fields. After all, even in the age of high-tech mercantile realism, the primacy of states as leading protagonists in the international political economy of money remains unchanged. Considering its comparative advantages in the domain of FinTech, China has become the world’s leading mastermind and innovator in the development of state-backed digital fiat money. And it looks like the ‘Middle Kingdom’ is on its way to be the first great power to play assertively with its own digital currency as a strategic card in the increasingly complex, unconventional and contested battlespace of e-finance.

It would be premature to prophesize that the experimental introduction of the e-yuan represents a masterstroke of economic statecraft or a ‘Sputnik moment.’ The project is not moving forward in a fast-paced way. Instead, its trajectory is sailing through the achievement of facts on the ground that constitute incremental milestones. This CBDC needs to cover the rest of the Chinese territory before it can transcend the confines of the Sinosphere, let alone steamroll the US dollar as a competitor whose superiority has been uncontested since Bretton Woods. On the other hand, Beijing also needs to address pressing internal macroeconomic and financial challenges that might bring systemic instability or even political fallout. However, the Chinese are willing to play the long ‘Great Game.’ From the long-range Weltanschauung associated with Chinese strategic thinking since antiquity, Zhongnanhai’s likely prognosis is that the journey of the thousand li necessarily has to start with small steps.

*This article was originally published on October 15, 2024.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.