Summary

The BRIC acronym has served to add a dramatic flair to shifting global power structures by envisioning a club of up-and-coming BRIC countries challenging a world order built on the bedrock of imperialism. But this isn’t accurate. The accord that is assumed in the BRIC grouping is imaginary. It doesn’t exist.

Analysis

Of course, that’s not to say that the sum economic power of the BRIC countries is not impressive. Quite the contrary, combined GDP growth in BRIC countries since 2001 is tantamount to the appearance of one new Japan plus a new Germany in the global economy [1]. But that’s just a development success story, not an international organization. The combined economic clout of the BRIC countries does not engender any kind of sustained foreign policy coordination, whether in political, military, or even economic affairs. And this shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. After all, this is a bloc borne not of diplomatic negotiation, shared ideology, or overlapping interests, but rather the turn of phrase of a Goldman Sachs analyst back in 2001; an analyst who, at the time, hadn’t even visited three of the four countries in question [2].

Consider the case of China and Brazil. Both are developing countries with the same presumed end-point: a highly-developed and diversified economy that is globally competitive. But, is it possible for both these countries to achieve this goal when they’re essentially following the same track and competing for the same markets, or will one of them be left behind? It’s quite possible that the truth lies in the latter.

Although China became Brazil’s largest trading partner in 2009, Sino-Brazilian economic relations have evolved somewhat of a north-south dynamic over the course of the past two decades. In other words, Brazil’s resource wealth has been used to fuel China’s industrial development. So far, the results have been a mixed blessing for Brazil. Its primary exports like soy and iron ore have boomed at the expense of value-added industries such as footwear and aircraft manufacturing [3]. Similarly, while China may be a valuable source of foreign investment, most of this money is targeted at infrastructure that can facilitate higher levels of primary exports [4].

These problems are so pronounced that Brazil’s manufacturing capacity is actually shrinking. In the 1980s, manufacturing accounted for 27 percent of Brazil’s GDP. By 2011, the number had shrunk to a mere 15 percent [9]. January of this year alone saw a month-on-month fall of 2.1 percent in industrial production [5].

Brazil thus finds itself in the unenviable position of riding an economic wave that might very well be short on long-term economic benefits. The deeper Brazil sinks into economic interdependence with China, the more domestic job creation opportunities it loses [9].

The government in Brasilia seems to be taking note of this. Just last week, Brazil’s foreign minister threatened to hold down the value of the real in order to help Brazil’s domestic industries compete with cheap foreign imports. As justification, he declared “we are not going to just sit by and watch while other countries devalue their currencies to give them a competitive advantage.” It’s pretty obvious who the ‘other countries’ in question are; or rather is.

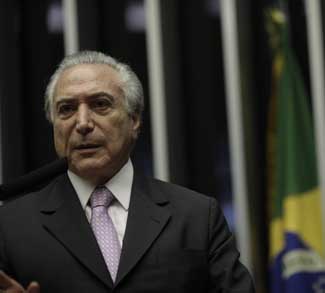

Interestingly, the economically corrosive nature of this BRIC linking may come to be a boon for Brazil’s relationship with the United States- a country that is paradoxically a better balanced trade partner by virtue of it being a market for Brazilian manufactured goods. The Obama administration delivered a massive snub to Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff this week by declaring that the United States won’t be extending the formality of a state visit for her visit in April because it’s an election year. This stance might have been forgivable had it not been announced during a state visit from British Prime Minister David Cameron. Yet, the Brazilian government has been relatively silent on the snub, and Rousseff seems willing to proceed without the pomp of a state visit. This seems to indicate a willingness on the part of President Rousseff to repair the damage done by her predecessor. Perhaps Brazil is eyeing an escape from the noose of BRIC economics.

And then there’s the military overlap between India and China. These two BRIC countries are currently locked in what might be termed as an ‘arms race: lite,’ behavior that’s not becoming of supposed close partners. Beijing recently announced that its annual defense budget would be $106 billion in 2012, excluding foreign procurement [6]. As always, analysts can only guess at what the real number will end up being. On the other side of the Himalayas, the Indian government jacked up its defense budget by 17 percent and it’s currently locked in negotiations over what could become the largest fighter-jet purchase that the world has seen in 15 years [7].

The list of geopolitical sticking points between these two BRIC countries is extensive. It includes China’s ‘string of pearls’ in the Indian Ocean and its patronage of Pakistan, a long-standing border dispute, and the continued existence of the Tibetan government-in-exile in India. But in the interest of brevity, there’s one overarching point that should be emphasized: both countries are starved for energy imports. They compete for the same sources and are desperate to ensure the security of shipping lines that snake through each other’s backyard. This is a strategic reality that precludes the two countries ever getting too close, no matter how catchy the proposed acronym is.

As for where Russia fits into all of this, a simple question will suffice: Will a nationalistic, re-assertive Russian foreign policy commit itself in any real way to the matrix of byzantine and often antagonistic interests stemming from three other developing countries? Probably not, and if for whatever reason the newly-coronated Putin government decided to do so, it would mark a radical departure from how Russia has historically viewed itself in world affairs.

The BRIC concept, birthed in the gilded halls of Goldman Sachs, had a kind of infectious logic to it ten years ago. It was like an ideological set of training wheels, preparing us all for international multi-polarity. However, its relevance as an analytical tool never extended beyond a brief period when fear of American hegemony was enough to smooth out conflicting interests among BRIC members. Fast-forward to the present and this is a bloc of four developing countries can’t even decide on the establishment of a BRIC development bank [8]. It is as it always has been: every BRIC for itself.