Summary

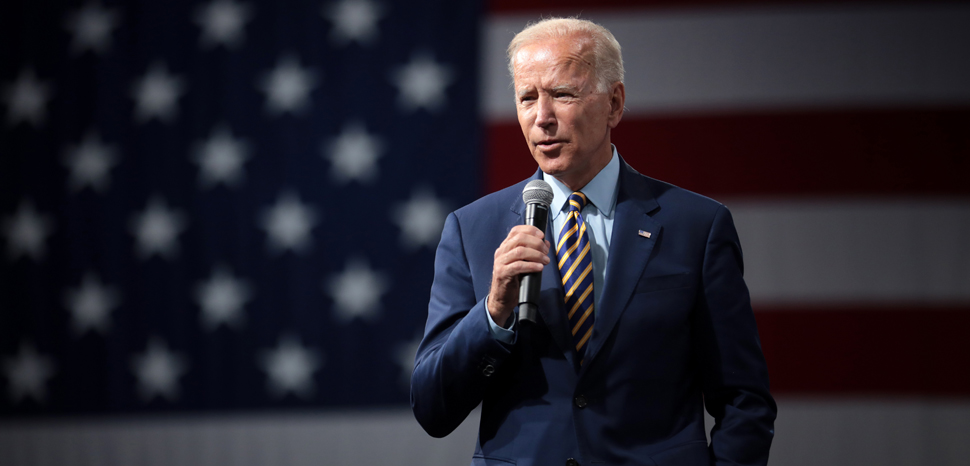

US president-elect Joe Biden did an interview with the New York Times earlier this week, in which he touched down on a variety of subjects ranging from the fate of the Iran nuclear deal to economic stimulus.

The discussion also broached upon what US-China relations might look like under a Biden administration. And, if taken at face value, the president-elect’s words will be causing considerable concern in Beijing. Put simply, they suggest that the Trump approach to US-China relations was no exception; rather, it could well become the rule moving forward.

Impact

There were two highly consequential tidbits on US-China relations under a Biden presidency.

The first is that a Biden administration would not immediately remove the 25 percent tariffs levied during the Trump administration – tariffs that currently cover nearly half of all Chinese exports to the United States. Biden would also seek to implement President Trump’s Phase 1 deal, which requires China to increase its purchases of US goods by nearly $200 billion in order to offset the bilateral trade balance.

Biden’s support of the Phase 1 deal is surprising given his damning assessment that it was ‘failing badly’ just a few months ago. But the pressure his administration will be under to maintain an assertive China policy is less so.

Public perceptions of China in the United States have cratered over the past few years. Some 73% of US citizens polled by Pew held an unfavorable view of China in 2020; at the dawn of the Trump administration in early 2017, that number was just 47%. In other polls conducted by Gallup, clear majorities reflect the belief that China regularly engages in unfair trade practices.

In other words: the US public is squarely behind the Trump approach to US-China relations, in spirit if not method, and this serves to limit the policy options of a Biden administration.

Public perceptions aside, there is also a growing elite consensus that US policy must adapt to the realities of contemporary US-China relations. Where unfair trade practices and information warfare by the CCP could previously be ignored under the illusion that China would eventually liberalize, and Beijing could endlessly buy for time with vague promises never-to-be-fulfilled, China has now begun to be treated as it is – a peer competitor with its own ideology and interests – and not as Washington wishes it would be.

Biden himself reflected this trend when he rejected Trump’s Phase 1 deal for not going far enough, decrying its “vague, weak, and recycled commitments from Beijing” that allow it to “[provide] harmful subsidies to its state-owned enterprises and [steal] America’s ideas.”

This brings us to the second and far more consequential revelation in the recent Biden interview: the president-elect’s proposal of a more coordinated approach to blunt the sharp edges of China’s assertive foreign policy.

In his words:

“The best China strategy, I think, is one which gets every one of our – or at least what used to be our – allies on the same page. It’s going to be a major priority for me in the opening weeks of my presidency to try to get us back on the same page with our allies.”

Here is the worst-case scenario for the Chinese authorities. It’s also a contingency that was cited in our initial analysis as one reason why President Trump might actually be considered the more favorable presidential candidate in the eyes of the Chinese state authorities.

The prospect of an alliance of like-minded countries acting in concert against China has long been the overarching fear in CCP strategic thinking. However, it’s only now that it has become a realistic possibility. There are two reasons for this: 1) The fading assumption that China will democratize (and with it the view that there are no contradictions between China’s system and the democratic world); and 2) the simple fact that China is now powerful enough to pose a credible threat to certain states, whether it be rival claimants in the South China Sea dispute or trading partners that are overly reliant on the China market.

Thus the battle lines are drawn in what appears to be another four years of antagonistic US-China relations. But where the Trump administration defined the bilateral relationship, a Biden administration could do much to define the international context of the relationship.

It’s worth noting that Biden’s “major priority” of forming a coalition of like-minded countries is easier said than done. US credibility is at a low ebb after the diplomatic reversals of the past four years, and the Chinese government will do everything it can to economically punish any state that hitches its wagon to Washington. The question then becomes: Is supporting the policies of a mercurial US administration worth the risk of incurring the far more consistent wrath of Beijing?

Different states will arrive at different answers.

Finally, there’s one country where president-elect Biden’s appeal to a more coordinated approach to China might be particularly welcomed: Australia. The country is by far the most economically reliant on the China market among its Anglosphere peeps, and likely because of this, it has been singled out by Beijing for a series of punitive trade policies (covered in greater depth in a recent timeline on China-Australia relations).

How the collapse of China-Australia relations plays out over the short-term could be highly consequential for Biden’s future efforts. China could well be attempting to make a cautionary example out of Australia in anticipation of US efforts to form a ‘united front’ among Five Eyes countries. Though yet to be felt in their entirety, the economic fallout of the trade war is expected to be severe. Will Canberra still be willing to get on board with other democratic countries and risk further economic retaliations?

President-elect Biden will be hoping the answer is “yes.”