China’s education reform has gained attention lately for its notable intensity. For instance, assigning “Xi Jinping Thought” – the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s highest guiding principle for the Chinese people and nation – as a new mandatory curriculum at primary and secondary schools, barring private tutoring to more effectively deter the influx of foreign ideas, and imposing “online game bans” to restrict the gaming activities of Chinese youth as a means of limiting “unhealthy” cultural habits. One ostensible impulse behind this approach to education is maximizing the party’s ideological-political primacy, which is crucial for Beijing to legitimize its autocratic governance. And such is impossible without promoting a stable ideological-political convergence between the government and the people. In this sense, managing the ideological-political education of young generations more exposed to western influence inevitably is a critical part of the CCP’s domestic policy efforts. As such, Beijing has attempted to reshape education for the Chinese youth through various policies and initiatives over the years.

Efforts to Reshape Education

Beijing has previously implemented top-down directives to integrate the CCP’s ideological fundamentals into national curricula and simultaneously offset western thoughts. For example, “Document 9” issued in 2013 called for a return to Maoist ideas and tactics to combat external ideological threats and identified “seven political perils” also known as the “Seven Don’t Speaks” to minimize the spread of western thought across the Chinese population. In 2015, “The Opinion” document also aimed to discourage western liberal ideas at schools while enforcing studying, researching, propagating Marxist-Leninism, and incorporating the theoretical system of “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” into textbooks and classrooms. And such directives aimed at shaping a “more Chinese” education environment have been put into practice through efforts such as textbook compilation and cleansing, curricula and faculty restructuring, and online propaganda.

China’s textbook reform led by the Ministry of Education has involved compiling new textbooks and removing existing ones. By promoting large-scale textbook compilation projects, such as the “red culture (红色文化)” textbook drive launched in Jiangxi province, the Ministry of Education has sought to incorporate a sharper focus on Chinese revolutionary history and CCP ideologies in textbooks for different grade levels from preschool through college. Concurrently, schools in almost all provinces of China have been guided to remove “inappropriate” selections from their libraries and avoid the use of imported textbooks.

In addition to reforming textbooks, Beijing has directed schools to revise their ideological theory courses and restructure faculty according to the CCP’s requirements. And when schools and teachers fail to meet the criteria, they are often disciplined. For example, Liaoning Daily, a provincial media outlet, investigated social science and philosophy classrooms across universities in China and subsequently released an open letter criticizing teachers for their unpatriotic perception of China and for being bad influences on students.

While making institutional reforms to restructure textbooks, curricula, and faculty in line with its ideological preferences, the CCP has also taken full advantage of its advanced technology to mobilize an extensive digital propaganda campaign through a smartphone application called ”Xuexi Qiangguo (学习强国).” The mobile app features a system in which users accumulate points by logging in, reading and commenting on articles related to the CCP ideologies, policies, and Xi Jinping Thought, watching history lessons and completing quizzes, all with the underlying goal of quantifying citizens’ ideological knowledge and loyalty to the CCP, especially among the tech-savvy younger generations.

The CCP has successfully popularized Xuexi Qiangguo and the app is among the most downloaded in China. And this process has involved compulsion. Party cadres have reportedly been required to download and use the app daily, and while it is not clear whether the mandate has also applied to non-cadre citizens, many have participated out of peer pressure, for online incentives, and due to a sense of competition cultivated by the in-app national ranking system based on point accumulation. Furthermore, there have been more top-down efforts to monitor and enforce user engagement of Xuexi Qiangguo by local governments. In provinces like Zhejiang, Hunan, and Fujian, the local governments have issued directives to improve underperformance in party members’ Xuexi Qiangguo participation rate and points accumulation, such as urging people to complete mobile registration and making sure the daily earned points don’t fall below specific numbers.

Implications

From reforming textbooks and curricula to digitalizing party propaganda, Beijing has been designing China’s education environment in such a way that allows the CCP to best exert its influence on Chinese students’ daily education. Beijing seems to have made good progress thus far, given that Chinese youth are developing into a coalition very supportive of Beijing’s nationalist ideological-political rhetoric. The ideological-political convergence of the CCP and the Chinese public could further empower Beijing’s legitimacy and allow the Xi administration to maximize its authority.

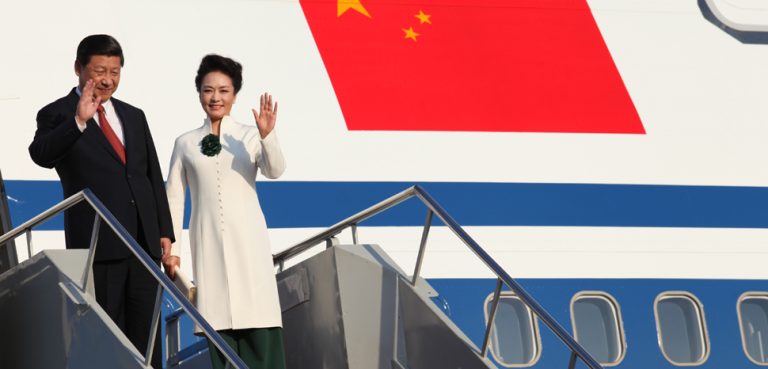

The process of Xi Jinping and the CCP expanding their authority has involved some dramatic moves, like the 2018 constitutional revision that removed presidential term limits and enabled Xi’s possible lifelong leadership. Most recently, the CCP adopted a landmark resolution honoring Xi’s nine years of leadership, highlighting its monumental historical significance to China’s rise as a great power. This makes Xi the only Chinese leader to earn symbolic political status after Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, two influential supreme leaders. With his elevated status as a historical leader, Xi may very well be set to serve additional terms. And such an assertive pursuit of political dominance by Beijing has been possible not simply because of China’s authoritarian system itself.

A 2020 study on Chinese public opinion revealed overwhelmingly strong support of the Xi administration, with over 95 percent of respondents reportedly satisfied with how Beijing under Xi has governed their country. Considering restricted free speech in China, it would not be surprising if the actual public approval of Beijing was lower. Still, the general sense reflected in the survey — that the Xi Jinping government remains a highly legitimate regime backed by a significant majority of citizens — should not be overlooked. Perceived concrete national accomplishments, such as an anti-corruption campaign, poverty elimination, containment of the COVID-19, and development of China as a global economic and military power have greatly contributed to Xi’s popularity. But at the same time, Beijing has undertaken persistent centralized efforts to integrate Chinese citizens deeper into its nationalist ideological-political agenda, as shown by the relentless education reform. Without the latter, mobilizing public support would have been difficult for the Xi government.

In large part, China’s perceived education crackdown is driven by Beijing’s ideological-political motivation to turn young generations into a nationalist coalition highly tolerant and approving of the government’s decision-making. In this sense, Beijing has more reason to reshape China’s education environment in its favor. The Xi administration would need a more supportive Chinese public than ever to legitimize its increasingly dictatorial tendencies. A tight ideological-political alignment between the government and the public will continue to be an essential condition, potentially hinting that Beijing’s current hardline nationalist approach to education could remain for the foreseeable future.

James Park is the 2021 YPFP Asia-Pacific Fellow. He is a graduate student in International Politics and China Studies at the Johns Hopkins University-Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies.