Summary

Kyaukpyu is a small fishing village of some 50,000 people located in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. This sleepy hamlet is where China wants to establish the next maritime hub of the Belt and Road Initiative. The plan is to construct a world-class deep-water port and free trade zone, thus allowing China’s Yunnan-based industries to gain easier access to global markets via the Bay of Bengal.

However, like some other Belt and Road projects, political concerns are muddying the waters. Kyaukpyu Port ranks highly on a long list of controversial Chinese development projects in Myanmar, a list that includes the cancelled Myitsone hydropower dam and the ever-contentious Letpadaung copper mine. The port’s detractors worry that it will force Myanmar into a subservient position of debt servitude for decades to come. Supporters argue that these concerns are eclipsed by the economic gains to be had from building a bustling new port complex on what is otherwise a largely underdeveloped swathe of Myanmar’s coast.

This backgrounder will explore the economic promise and geopolitical ramifications of the Kyaukpyu Port.

Background

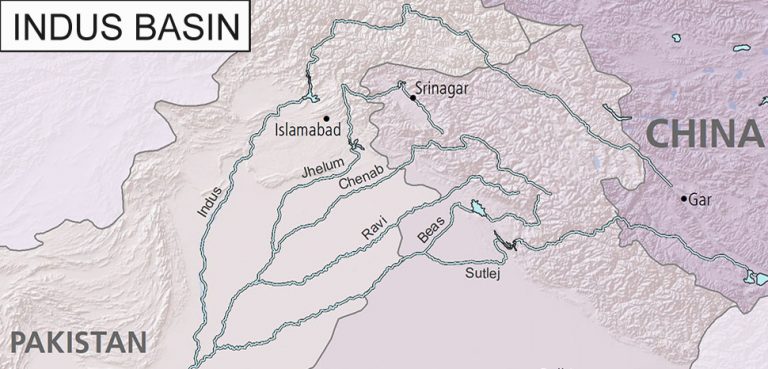

Kyaukpyu Port is similar to Belt and Road projects elsewhere, notably Gwadar Port in Pakistan and Hambantota in Sri Lanka, the latter of which passed into China’s possession on a 99-year lease after the Sri Lankan government found itself mired in fiscal crisis (in part due to the loans needed to build the port in the first place).

Yet in the case of Kyaukpyu Port, it’s worth noting that Myanmar has had a strong historic aversion to being drawn too closely into China’s economic orbit, which has resulted in an arms-length approach to various Belt and Road projects. This aversion was evident in the popular outcry that led to the (perhaps temporary) demise of another Belt and Road project: the $3.9 billion Myitsone dam, which intended to build a series of hydropower stations on the headwaters of the Irrawaddy River. The dam was nearly universally opposed by the Myanmar public due to its social and environmental costs (over 15,000 people would need to be relocated), and the terms of the original deal, which were viewed as excessively favorable for China (the project would see 90% of its electricity exported to China’s Yunnan province).

Put simply, Naypyidaw’s baseline attitude toward Beijing is one of skepticism. But in Myanmar as in other locations along the BRI’s economic corridors, there aren’t many alternative investors willing to step in and supplant Beijing’s willingness and ability to fund major infrastructure initiatives. With the advent of the post-2010 reform process, Myanmar opened up its domestic political process, secured sanction relief, and attracted new sources of investment – all of which served to lessen the country’s reliance on China. However, this rapprochement suffered a breach amid the Rohingya crisis of 2017, followed by open rupture after the 2021 coup effectively ended the country’s pseudo-democratic experiment. Now, Myanmar once again finds itself isolated and reliant on Chinese finance and support, and this reliance is reflecting in the terms of the Kyaukpyu Port and other BRI projects.

Kyaukpyu Port

Though the Kyaukpyu Port was first proposed all the way back in 2007, the project has struggled to get off the ground ever since. This is only partially due to the aforementioned skepticism on the part of the Myanmar authorities. Another drag on the project is the unclear economic logic underpinning it. Pre-coup there were numerous competing facilities in the neighborhood, most notably the Japan-financed Thilawa Port just south of Yangon. Thilwa Port can handle vessels of up to 20 thousand DWT (tons deadweight) and 200 meters in length; it has benefited from ‘spillover’ from the nearby Yangon Port, which is increasingly constrained by the trade boom of the past decade. Thilawa’s main external patron is Japan, which has poured hundreds of millions into expanding the port’s facilities, and those of a nearby industrial park. Post-coup trade volumes have dried up and major players like Adani Ports have been forced to divest or risk falling afoul of Western sanctions.

Due to the country’s pre-existing infrastructure networks, many of which link up with bustling metropolis of Yangon, critics assert that Kyaukpyu would be less about developing the Myanmar economy in a holistic sense and more about creating a new and mostly China-owned economic conduit linking Yunnan province with the Indian Ocean.

In other words, the overriding logic of the project has always been geopolitical rather than economic.

Negotiations over Kyaukpyu Port have been ongoing since 2015, when the project was originally awarded to China’s CITIC Group, one of the country’s first state-owned investment consortiums. The original terms of the deal were controversial to say the least, particularly the $7.3 billion price tag that was initially floated. By way of contrast, the first phase of the Hambantota Port project cost just $361 million back in 2008, and Gwadar Port cost about $248 million to build back in 2003.

How that $7.3 billion would have been spent will remain a mystery. For its part, according to the CITIC, the port would have an annual capacity of 4.9 million containers, which is around the size of the Hanshin ports servicing the Osaka-Kobe region of Japan. Another mystery is the fiscal gymnastics that would have allowed a country with a GDP of just $71 billion (about the same size as Luxembourg) to pay the money back without triggering fiscal meltdown. The deal’s original supporters within the Myanmar government maintained that the sum would be repayable, and that the project would proceed on a phase-by-phase basis, with a certain threshold of success having to be reached before the next phase could proceed.

Another point of contention was the ownership stake in the port. CITIC originally sought a controlling stake of anywhere between 70-85% in the project.

The original terms of the deal were subsequently renegotiated by the Suu Kyi government following the 2015 election. As a result of these talks, the scope of the project was significantly downgraded, with the port to be just one seventh the size and capacity of the original plan. The fiscal burden was also reduced for Myanmar, which would have to borrow/pay around $1.3 billion in exchange for a 30% stake in the project, up from the original 15%.

Yet even with these more favorable terms, the project remained bogged down in a state of regulatory limbo in the lead-up to the 2021 coup, with the CITIC still submitting environmental and social impact studies in late 2019, only to have COVID-19 destroy any economic and political impetus for the project soon after. The dynamic has changed since the Military Council took over in 2021. Heavily sanctioned by the West and fighting a slow-burn civil war throughout the country, the Myanmar authorities have lost any leverage they previously had dealing with China. Beijing on the other hand is happy to engage with Naypyidaw and lessen its international isolation, though now it has a free hand to push for the resumption and expedition of the Kyaukpyu Port project – and this is precisely what China is doing.

A Belt and Road project with strategic significance

There’s a significant military dimension to Kyaukpyu, as the location is geopolitical significant and would grant China another outpost in its ‘string of pearls’ strategy meant to encircle India in the Indian Ocean. The site is almost directly across from INS Varsha, near India’s coastal city of Visakhapatnam. INS Varsha will be the future headquarters of India’s Eastern Naval Command. The scope of the Kyaukpyu project – speak nothing of the size of the required loans and their potential to ensnare Myanmar’s finances – implies that long-term military calculations are underpinning China’s enthusiasm for the project. However, the permanent stationing of PLA military assets in Myanmar remains highly unlikely given the country’s longstanding sovereignty sensitivities vis-à-vis Beijing.

Kyaukpyu Port could also help to lessen China’s dependence on seaborne energy imports. In fact, gas and oil pipelines have already been built to link Kunming and Kyaukpyu. Paradoxically, these pipelines actually served to further inflame local opposition against future stages of Kyaukpyu Port, as these early projects were characterized by poor compensation for land purchases, environmental shortcuts, and overreliance on foreign labor at the expense of local workers.

Of course, there’s an important economic dimension as well. Kyaukpyu would give Yunnan-based industry easier access to global markets via the Indian Ocean. But even more importantly, it would provide new political impetus for high-speed rail projects linking Ruili on the China-Myanmar border to Mandalay and eventually the coast. A contract was signed in 2011 to establish a Kunming-Rangoon rail corridor, but the project was cancelled in 2014 following widespread protests against the terms of the deal, which would have granted the railway to China as a 50-year concession. Road projects would also shadow the rail corridor between Ruili and the coast to improve transport capacities for goods moving from Yunnan to Kyaukpyu Port.