Lebanon was once called, perhaps inaccurately, the ‘Switzerland of the Middle East’ prior to the 1975 onset of a 15-year civil war. Not until October 1989 did members of the Lebanese parliament (elected in 1972) accept a constitutional reform package.

Today, Lebanon’s government specifies that a Maronite Christian serve as president (though the seat is currently vacant), a Shia Muslim as speaker of the National Assembly, and a Sunni Muslim as prime minister. Parliamentary seats, cabinet posts, and senior administrative positions must include equal ratios of Christian and Muslim officials.

Modern-day Lebanon, though, is rife with corruption at the highest levels that includes funneling monies to terrorist organizations, notably Hezbollah. In recent years, attempts by both the Lebanese and American judicial systems to unmask the corruption within the nation’s banking industry have been met with stout opposition.

In 2019 a poorly managed spending binge, initiated by the Bank of Lebanon (BDL), pushed up debt and caused a near-total collapse of the Lebanese economy. Rival factions pointed fingers, and foreign lenders demanded reforms.

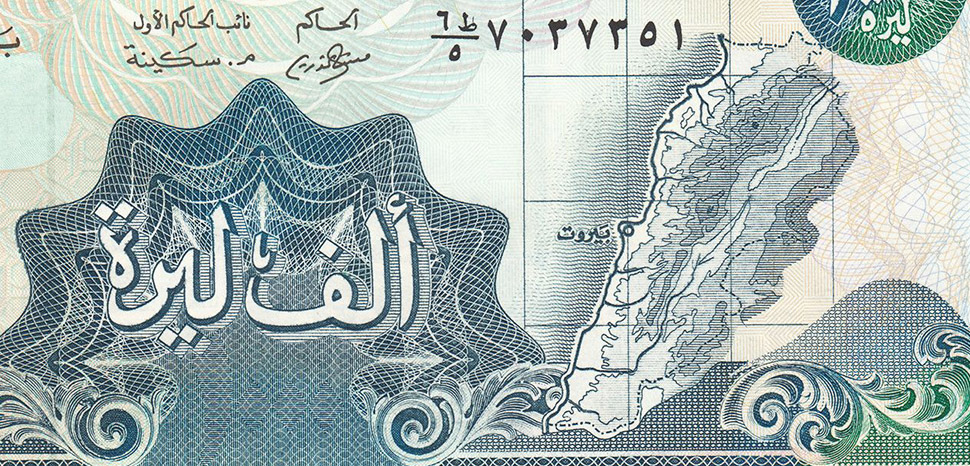

The World Bank ranked the Lebanese collapse, which saw the Lebanese pound lose 98 percent of its value against the U.S. dollar, plunging more than 80 percent of Lebanese citizens into poverty, as one of the worst in 150 years.

After the terrible Beirut port explosion of August 2020 killed hundreds and left 300,000 homeless, protests led to the resignation of the Lebanese government. Prime Minister Hassan Diab blamed “a system of corruption … deeply rooted in all the functions of the state.” He added that “corruption cases are widespread in the country’s political and administrative landscape; other calamities … are protected by the class that controls the fate of the country.”

In 2020, BDL began selling dollars at a preferential exchange rate, supposedly to benefit importers and the public and to support the Lebanese pound. When the effort yielded no tangible public benefits, United for Lebanon, an association of attorneys pledged to fight corruption, started to ask: “Where did the money go?”

The group sued BDL governor Riad Salameh, Antoun Sehnaoui, chief executive of Société Générale Bank of Lebanon (SGBL), and four of Lebanon’s main exchangers for “money laundering crimes resulting from currency trading operations with the intent of exposure to the national currency.” United for Lebanon founder Rami Ollaik notes that “the case kicked off with a violation of the cabinet decision to back the Lebanese pound.”

In August 2021, appellate public prosecutor Ghada Aoun filed criminal charges against Michel Mecattaf, whose transfer taxi company allegedly illegally laundered billions of dollars, in addition to a number of Mecattaf associates, and Salameh and Sehnaoui and their banks.

Rather than respond, the defendants and their surrogates began attacking Aoun personally as “too close” to then-president Michel Aoun and too willing to bend or break the law to win her case. Yet Aoun persevered despite a decision by cassation public prosecutor Ghassan Oueidate to remove her from the case.

Lebanese media jumped on the anti-Ghada bandwagon, eager to report on what her enemies called a “mutiny” (and her supporters called a “judicial uprising”). Official Lebanon, fearing her investigation would expose even more corruption, sought to suppress her case. Sehnaoui’s attorney accused her of slandering his client, who had refused to appear in court.

Ollaik in December 2021 condemned efforts by political groups to thwart the prosecutions, noting that “files and requests … disappear and reappear, and legal documents are lost while decisions are made without regard to an ethical code.”

But things got worse. Banks stopped lending money altogether, such that Arab News reported in February 2023, “Lebanon could be headed to oblivion.” The Lebanese pound dropped to 81,000 to the dollar and central bank financial operations fell to $10 million per day. Salameh, still at the helm despite the charges, claimed that the black market in Lebanon was “outside the control of the central bank, which has become unable to solve crises.”

Even worse, Charles Arbid, president of Lebanon’s Economic and Social Council, lamented that, “We fear that Lebanon as we know it is changing under the leaders who could not care less about its fate.”

There is still no sitting president, as Michel Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement clashed with Hezbollah leaders who wanted to install an ally of theirs.

Meanwhile, Ghada Aoun formally charged SGBL and Sehnaoui with money laundering and froze the banks’ funds, then turned the prosecution over to Judge Nicolas Mansour. Salameh again refused to attend a scheduled April 3 hearing.

Salameh’s term at BDL ended on July 31, and the man once called one of the world’s best bankers is now the subject of financial crime investigations in six European countries; he has also been sanctioned by the United States and Canada, and is wanted by Interpol.

Salameh, who denies any wrongdoing, and his associates allegedly transferred about $330 million from the BDL from 2002 through 2015 to purchase luxury real estate and other assets in Europe. His 2016 financial engineering scheme weakened the banking sector, fueled extensive public debt, and harmed the Lebanese citizenry.

But his wrongdoing is just the tip of a corrupt iceberg.

Sehnaoui and SGBL are the primary defendants in a lawsuit filed in U.S. district court by the families of victims of Hezbollah terrorism – specifically attacks in Iraq in coordination with Iran’s Revolutionary Guard between 2004 and 2013.

Part of this is due to SGBL’s 2011 acquisition of the defunct Lebanese Canadian Bank, which had been cited for an international money laundering operation to provide direct financial support to Hezbollah.

In the civil suit, plaintiffs allege collusion with Hezbollah by SGBL, Middle East Africa Bank, BLOM Bank, Byblos Bank, Bank Audi, Bank of Beirut, Lebanon and Gulf Bank, Banque Libano – Française, Bank of Beirut and the Arab Countries, and Fenicia Bank.

After the lawsuit was filed in 2020, defendants repeatedly stalled proceedings, even seeking to have the claims dismissed. The banks are accused of knowingly providing extensive and sustained material support, including financial services, to a foreign terrorist organization and its alleged companies, social welfare organizations, operatives, and facilitators. Magistrate Judge Taryn Merkl is awaiting receipt of bank records from the Lebanese government by April 14, 2024.

If there are any heroes in Lebanon, Aoun deserves a medal even if she oversteps now and then. She was the first attorney to apply Lebanon’s 1953 Illicit Enrichment Law and the first to apply an October 2022 law on lifting banking secrecy and expose the truth of funds loaned by the BDL to several banks and transferred abroad.

Her investigations also ended a tainted fuel deal that had lasted 15 years under terms unfair to the state, in addition to uncovering hidden ties and dangerous infractions in numerous government agencies.

For her good deeds, she was targeted by organized smear campaigns for merely opening investigations into high-level corruption. Her work helped expose the ties between Lebanese banks and Hezbollah that are now being litigated in the U.S.

Sixteen years ago, Michael Young wrote that Lebanon’s chief challenge was figuring out how to hand power over to broader governance structures.

Today, the fractionalization that enables looking the other way at bad actors from one’s own constituency still plagues the tiny nation.

The rule of law must prevail if Lebanon is to recover from these wounds of its own making.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.