The West has taken one step closer towards military action against Syria after France and the United States warned Syrian President Bashar al-Assad that there would be a serious response to last month’s chemical attack in Syria. Now, as rifts continue to widen during the G20 summit in St. Petersburg, the UK government has come out claiming to have evidence of sarin gas at the site of the attacks that took the lives of thousands of civilians, including children, according to sources in the Syrian opposition. In preparation for a possible attack, Washington has already dispatched a fourth warship to the Mediterranean Sea.

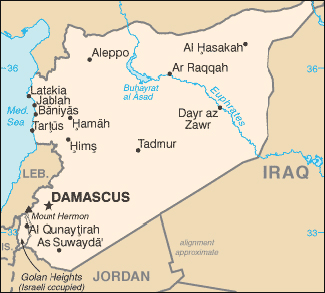

From a purely strategic point of view, the United States and its allies are faced with several scenarios in dealing with the situation in Syria, and there is no consensus over any specific option. Among the possible scenarios is an intervention to control chemical weapons sites in Syria. This would theoretically prevent the Syrian regime from using chemical weapons against opposition fighters, while preempting a situation by which the weapons come to be controlled by the rebels, particularly the more radical factions. US Special Forces are already training in Jordan to take control of chemical weapons sites in case Assad losses control over Syria. Nevertheless, the experience of Iraq still looms over any plan that envisions boots on the ground.

Alternatively, the US could target the Syrian military units responsible for the execution of the chemical weapons attacks. The aim of this kind of operation would be to punish al-Assad and to send a message of the kind of consequences that await him should he ever consider the use of chemical weapons in the future. The disadvantage of this scenario is that it may take a relatively long time until US intelligence gathers enough information on the targeted Syrian units; though some of this time has already been bought by President Obama in taking the intervention question to Congress. Another drawback of this tactic would be a possible spiraling involvement of the United States in a conflict that does not seem likely to end anytime in the near future.

The third option brings everyone back to the suggestion favored by the Turkish government: to impose a no-fly zone over Syria. However, neutralizing the Syrian Air Force does not mean neutralizing the combat power of the Syrian armed forces, embodied in particular in its artillery capabilities. What makes this option even more unfeasible is that it is very expensive, because it requires the use of hundreds of aircraft, as well as ground and naval bases.

Then there is the longstanding option of arming the Syrian opposition, providing them with weapons, ammunition and, and anti-tank missiles. Yet here too the burden of history looms, as the US fears a repetition of its painful experience in Afghanistan, where US intelligence supplied weapons to the Afghan mujahedeen to fight the USSR, and these same resources eventually came to nurture al-Qaeda. Consequently, the US fears armed battalions affiliated to al-Qaeda in Syria will get their hands on American weapons and turn them on US interests in the region.

All available data points to a limited sortie against Syria, one that takes the form of surgical bombing raids on chemical weapons facilities, long-range missiles, or even Air Force installations. The action would be calculated to be innocuous enough to avoid inducing a response that further destabilizes the region and perhaps even the world. In this, the US would be betting that Assad and his allies in Iran and Russia would absorb the surgical attack and respond with small-scale punitive actions and propaganda, and the situation wouldn’t spiral out of control.

However, what can ensure that things would stop at this point? What can ensure that this surgical attack would not roll into a regional war?

As the US threatens direct intervention over chemical weapons, the opposite front is also escalating the severity of its tone. The Iranians have declared that any direct intervention in Syria would involve serious repercussions for the region and the interests of Washington. There is also Russian support to consider, which though unlikely to precipitate direct military conflict, could complicate international coordination in containing a spiraling regional conflict.

The Syrian government approval of the United Nations’ request to inspect chemical attack site in Ghouta came after contact between the Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and his Syrian counterpart Walid El-Moalim. Russia welcomed the agreement between Syria and the United Nations, warning the West to wait for the UN results before launching a possible military operation in Syria. They also asked the US and its allies to think logically so as not to commit a “tragic mistake.”

On the one hand, if a Western strike led to big splits in the Syrian army, they would probably not stay behind to protect chemical sites from falling into rebel hands. Consequently, there would be a potential for rebels taking control of chemical weapons sites. It is possible that this would lead to catastrophic consequences, including the confiscation of chemical weapons by a new radical fundamentalist government, or the sale of arms as a trophy of war to non-state actors like terrorist or criminal groups.

Ultimately, the question remains: If a US military intervention caused the overthrow of al-Assad or terminally weakened his authority, who will gain control of chemical weapons after he’s gone? Is it Saudi Arabia-backed Sunni groups? Or the Shiite militias backed by Iran?

Whichever group ends up taking over, it would result in a serious security dilemma for Western governments.