Since the 1980s, India has enjoyed a growing workforce, fewer retirees, and low fertility rates that have fueled significant economic growth, a coveted opportunity known as a demographic dividend. The fortuitous trend is projected to propel India’s modernization and foster geopolitical influence as an energetic population creates an enormous, sustained expansion of the country’s economy. Some project that a period of exceptional growth will continue beyond the middle of the century. Yet though the demographic dividend has so far been positive for India, it has recently been overshadowed by uneasy geopolitical, economic, and demographic threats that portend instability amid India’s rise.

India’s New Geopolitical Turmoil

The BRICS alliance has been ascendent in 2024, acquiring new members and positioning itself as a formidable counterbalance to Western hegemony, with India as a crucial partner. However, US president-elect Donald Trump has now publicly identified BRICS as a threat to US dollar dominance, promising to impose 100% tariffs on BRICS countries seeking to undermine the US dollar through the use of a common currency. For the United States to explicitly target BRICS over its ambitions further complicates the geopolitical arena and creates additional tariff risk for large, exporting countries like India. Furthermore, replacing America’s massive import demand with that of other developed countries is unlikely in the near term, as US demand accounts for nearly 18% of Indian exports and Europe continues to experience economic weakness.

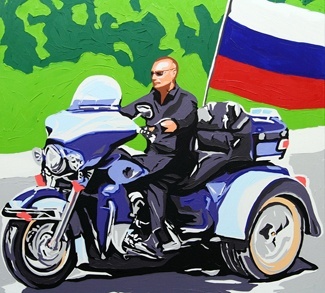

Beyond BRICS, India has remained neutral in the Russia-Ukraine war, alienating Western nations as it asserts autonomy from NATO interests. India has continued importing sanctioned Russian oil, while Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Moscow in July and Russian President Vladimir Putin is confirmed to be visiting India in the new year. Such events provide much needed funds and legitimacy to Russia’s war economy, at a time when the West has sustained and increased support for Ukraine financially and militarily. The United States has responded by imposing sanctions on 19 Indian companies “supporting” Russia. India’s discordance with larger, distant nations poses an added risk for a country still mired in neighboring disputes with a nuclear-armed Pakistan.

Further complicating India’s role internationally, India and Canada have engaged in a very public, ongoing diplomatic feud over alleged conspiracies by the Indian government to assassinate Sikh leaders on Canadian soil. The ensuing dispute has led to the expulsion of diplomats along with ongoing accusations and investigations between the two countries.

Tensions reached an apex during a protest in Canada last month. Sikhs supporting Khalistan separatism, a movement pursuing creation of a Sikh homeland in India’s Punjab region, clashed with pro-India Hindus during a visit to Canada by an Indian consular official. Since then, US officials have charged an Indian national in the assassination of a Sikh political activist and implicated an Indian official as an accomplice.

Through such disputes, India has positioned itself as a bulwark to Western interests, at a time in its development when trade relations and geopolitical simpatico are necessary for the fledgling nation. Moreover, India is not ascending in a global environment that is welcoming to foreign trade expansion. Instead, Western tariffs, sanctions, and geopolitical tensions pose a major threat to India’s export-led growth and could destabilize or shorten its demographic dividend, hampering sustained development of its economy.

In comparison, China’s ascendence, beginning in the 1980s, was nurtured by rapid globalization and reductions in tariffs and trade barriers, culminating in China joining the World Trade Organization in 2001. As China liberalized its economy, it became the main source of cheap goods available to developed countries, a process welcomed by the United States. As a result, China has been able to acquire significant amounts of financial assets and dollar-denominated wealth due to an ongoing trade surplus with the U.S., catalyzing long-term stability and development. If similar avenues for growth and wealth creation are not available to India in the future, the country faces reduced prospects for growth, foreign investment flows, and job creation, thereby risking its demographic opportunity.

Warnings Signs of a Slowing Economy

Despite generally positive headlines on India’s economy, economic expansion slowed to 5.4% in July-September – a surprising, lackluster number for a country expected to be an emergent powerhouse of global growth and alarming some economists that had predicted growth of 6.5%. This marks the first time in four years that annual growth is expected to fall below 7%, and indications suggest the Indian government’s lower target of 6.5% for the year will be difficult to achieve. In contrast, when China was capitalizing on its demographic dividend between 1978 and 2017, GDP growth averaged above 9%.

Worse yet, stubborn upward pressure on food prices has pushed overall inflation above the RBI’s 6% upper limit, effectively stymieing near-term stimulus from the RBI that could re-accelerate growth. Inflation has been a continued threat for many countries and India has not been immune to such pressures. If inflation proves to be in a secular phase, meaning persistent and reflecting structural changes to the global economy, India’s growth potential may be constrained during a period when its demographic opportunity for growth is optimal.

India’s Demographic Decay

India’s demographics are already becoming less favorable as fertility rates fell below two in 2021, a level below replacement and typical of fully developed, Western economies. As of 2022, India’s population growth remains below 1% and the median age continues to climb, signalling a maturing of the country’s demographics. The fertility rate is projected to continue downward, hitting 1.29 by 2050. Low fertility coupled with a young but ageing population functions like a demographic debt. It helps propel the country in the near term but acts as a tailwind in future years as the population ages and draws on tax revenue from a declining working population. As some developed countries have learned, low fertility can lead to unstable social welfare systems and constrained productivity.

India’s current demographic trajectory echoes past trends in Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea. Both countries previously experienced exceptional growth driven by ideal demographics but now suffer from low growth and burdensome debt levels partly due to deteriorating demographics, a situation known as “Japanification.” Some countries have taken drastic measures to prevent the feared condition of economic stagnation, which currently risks spreading to China and Europe. China now formally pays couples to marry early and encourages higher fertility rates after having imposed the one-child policy beginning in the 1970s. Meanwhile, Russia has passed legislation prohibiting the spread of “child-free” culture that policymakers have blamed for low fertility rates. Countries have found it exceedingly difficult to reverse low fertility rates, and India may find it impossible to meaningfully reverse the trend as well.

Whither the Indian Economy?

Demography may be destiny under ideal conditions, but in a global economy where trade partners are imposing destabilizing tariffs, antagonism to globalization is growing, and regional conflicts are abundant, lofty growth and geopolitical prowess are no longer a given for India.

India’s most recent economic weakness may eventually be overcome with falling inflation and stimulative policies, but the country’s economic and political ascendence challenges Western counterparts and requires consistent and growing trade with wealthier nations. If the country cannot position itself to avoid new tariffs, take advantage of a globalized economy, and increase its population growth to sustainable levels, it may find itself wasting the remainder of its demographic dividend.