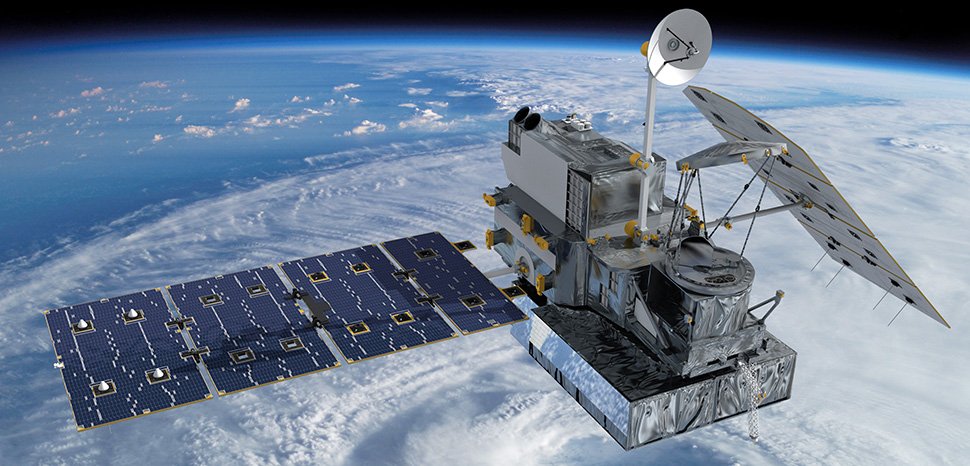

Following Tehran’s launch of three satellites into space, Iran could represent a significant threat to Western aerospace systems, particularly amid the rocky ceasefire deal for the post-October 7 Israel-Hamas war.

With Iranian nuclear and satellite capabilities on the rise, Israel and Western entities should remain vigilant for disruption attempts against Israeli and Western equivalent systems, particularly for communication and surveillance hindrance purposes in the face of Israeli attacks on Iran.

Alongside the obvious danger of attacks on government satellite systems, attacks on commercial satellites could also risk data loss. Such loss or theft could prove dangerous in the hands of hacktivists and nation-state actors alike, including obstructing Western visibility into Iran’s nuclear activities. Moreover, for both commercial and federal systems, respectively, compromised defense-related data as well as the protected health information (PHI) of patients in hospitals with impacted satellites could prove critical. In terms of attack type, backdoor installation via social engineering could pose a stealthier alternative to the more closely studied supply chain attack.

In addition to the well-known distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) and supply chain methods of attack used to overwhelm and infiltrate satellite systems, backdoor attacks present a more elusive attack often introduced to aerospace systems through social engineered infection of users with privileged access. To explore this subject in greater depth, MIT-trained Assistant Professor at Cornell University’s Aerospace ADVERSARY Lab, Dr. Gregory Falco, LEED AP, was consulted. Dr. Falco provided the following insight (text minimally revised for context):

The bus is what facilitates all communication across the space vehicle. Usually, subsystems are reporting telemetry data over the bus to the brains of the satellite for consistent coordination. When something is chatty, it could either mean that it is programmed incorrectly or it’s sending too much data back. It could be sending data back to the brain to flood the brain with errant messages or for other malicious activity.

As to how a chatty bus might indicate an attack attempt such as a backdoor installation, Dr. Falco explained:

These kinds of vulnerabilities are also often used in supply chain attacks due to the many legacy parts of the satellite vehicle in question. [These parts] are [sometimes] operated or managed by an old supplier who does not bother to update their codebase or has third party entities engaging with operations and over-the-air updates. A chatty bus is a common sign of a backdoor installation but given the lack of runtime monitors on the edge of the vehicle, it is difficult to decipher the cause of the chattiness [noise].

Defenders can therefore investigate beyond a DDoS or supply chain attack to also assess instances of chattiness for social engineering indicators both in the content itself as well as any suspicious communications received by users with privileged access to the systems in question.

The prolific insider threat of privileged users falling victim to social engineering is prominent across industries. As Iranian social engineering attempts against Israel and the U.S. have spiked against the backdrop of the Israel-Hamas war with threat actors such as the Iranian state-sponsored cyber-espionage threat actor APT42 and UNC1549 which has historically introduced backdoors on target systems, aerospace organizations should remain vigilant toward emails and other forms of communication with geopolitical themes. These communications could mention Israeli hostage release and might be composed in English, Hebrew, or another language spoken in a country seen as supportive of Israel and might focus on the Israel-Hamas war or similar political themes. If a user opens and clicks on a malicious link or downloads a weaponized executable, a backdoor could be installed on the user’s device or system. An example lure email might contain terms like:

جنگ (jang, “war” in Farsi) or ומתן משא (masa u’matan, “negotiations” in Hebrew) as well as “Apply now” or הגש מועמדות למשרה זו כעת andעבודה (“Apply now” and “work”, respectively, in Hebrew) to project a pretense of diplomacy and career opportunities, respectively.

Messages could be analyzed for spoofed sender sources by comparing the email header’s From field against its return-path. If they do not match, analysts should use open-source tools as well as host and network logs to assess for other appearances of the suspicious domain names and email addresses observed in the return-path, with emphasis on Farsi words or other potential ties to Iran. Phishing attempts can also be performed parallel to other attacks against aerospace systems, such as DDoS attacks which threat actors sometimes use to distract security analysts.

Artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to help examine noise captures in both audio and text format, with a focus on transliteration and translation. This function could be used together with a Persian Farsi human interpreter and translator to clarify the audio noise and any corresponding text obtained by the AI speech-to-text dictation feature.

From a response standpoint, the AI could be trained to identify possible backdoors installed by Iranian threat actors by analyzing for Farsi terms or code strings during code reviews. These reviews would function as a routine method of input sanitization in addition to regular security updates. The AI would be paired with these sanitization reviews by using heuristic analysis to assess content designated as suspicious according to a lexicon compiled from ongoing findings in both satellite device and worker communications.

The Persian-language specialist could then advise on any whether any of the aerospace system server logs contain Farsi text that would resemble backdoor code. This same AI system could also assess the contents and origin of emails and other messages received by aerospace workers.

When watching for possible infiltration tactics, aerospace defenders should be on the lookout for a wide range of techniques, possibly occurring simultaneously and against multiple geopolitical targets. In the case of Iran during the Israel-Hamas war, threats against both government and private aerospace systems pose the unique threat of obscuring not only monitoring of Iranian nuclear capabilities but also of the targets’ accessibility to and retention of their own data. AI could be leveraged to heuristically analyze content to prevent cyberattack in both a backdoor installation capacity and a general social engineering capacity.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.