Tales of intergalactic conflict have inspired novelists and captivated Hollywood audiences alike offering introspective explorations of the human condition on a cosmic scale. Asimov’s “Foundation”, Lem’s “Solaris”, and Lucas’ “Star Wars” franchise advanced thought-provoking visions of humanity’s future amidst a desolate and untamed celestial landscape. Today, epic battles waged against rival factions across vast interstellar distances increasingly serve less as thrilling adventures tantalizing the impressionable human imagination and more as allegories for contemporary geopolitical tensions.

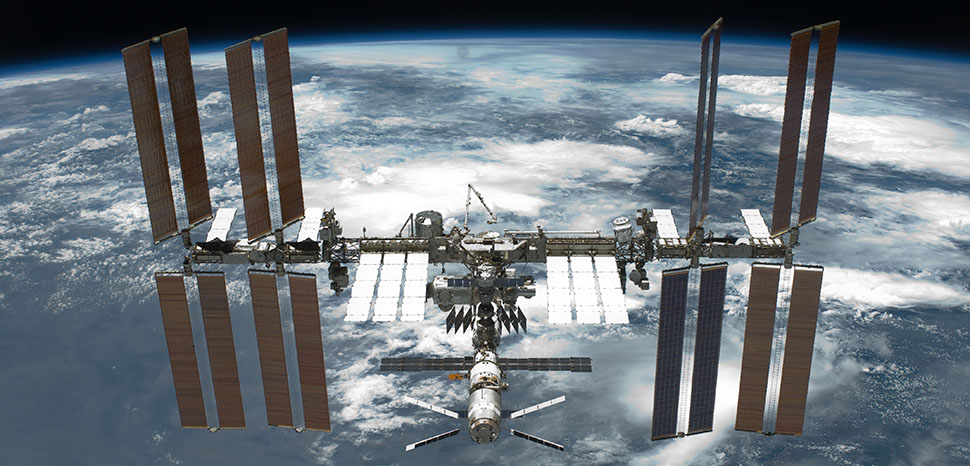

The Artemis Accords – spearheaded by the United States, alongside the European Union’s Strategic Compass, NATO’S Allied Air Command and Space Centre of Excellence; the deployment of Space X satellite constellations; the operational prowess of the Soyuz launcher and the Galileo spacecraft; the establishment of sovereign Space Forces and geospatial intelligence capabilities such as Airbus Defense and Space; and the dynamic evolution of the “New Space” economy collectively portend of humanity’s burgeoning endeavors beyond the confines of Earth’s atmosphere.

However, with this progress comes new challenges. The escalation of militarization and weaponization in outer space has become an urgent issue of concern. The once-fictional notion of using nuclear space weapons to incapacitate satellites with powerful energy waves is now a tangible reality. Nations across the globe are making unprecedented strides in both civilian space exploration and its military application. According to the Secure World Foundation’s annual Global Counterspace Capabilities report, there is a noticeable trend wherein an increasing number of countries are harnessing space to bolster their military capabilities and safeguard national security. This involves the development of a wide array of defensive and offensive technologies with dual-use applications.

Notably, countries like France, India, Iran, Japan, and North Korea are actively investing in counter-space programs, while major players such as China, Russia, and the United States are leading the charge in research, development, testing, and operationalizing systems and weapons. This proliferation of capabilities significantly heightens the risk of potential conflicts in space.

The governing international treaties concerning outer space, established in the 1960s and 70s, lack clarity regarding military activities in space, let alone the potential for armed conflicts. These treaties are outdated and ill-equipped to address contemporary challenges. Technological advancements have outpaced the legal framework’s ability to adapt, particularly concerning the intersection of civilian and military activities in space and the potential for conflict.

Every terrestrial war is now simultaneously a space and cyber war requiring identification and active monitoring of threats from space assets and threats to space assets from rival states. In the US Department of Defense assessment, China and Russia in particular pose significant risks to space assets through various means such as cyber warfare, electronic attacks, and ground-to-orbit missiles capable of destroying satellites and space-to-space orbital engagement systems, thus disrupting civilian infrastructure on earth. This has prompted the United States to allocate substantial resources to bolster its Space Forces, with budgetary allocations to the space domain doubling from $15.4 billion to $30.3 billion between 2021 and 2024.

Source: US Department of Defense

Yet, the United States is not alone in grappling with the complexities of space warfare. Nations worldwide are committed to ensuring freedom of operation in space while deterring and countering threats to their systems. This includes the establishment of independent Space Forces and participation in multinational space command formations, such as those within NATO and other allied alliances. They collectively operate in a relatively congested environment of independent Space Forces of China, Russia, Iran, France, Colombia, and Spain as well as within joint multinational space command formations of NATO Allied Air Command, Australia, Canada, India, Italy, South Korea, and the United Kingdom, among others.

Recent conflicts, such as Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, have highlighted the evolving nature of warfare in the digital age. The reliance on open-source commercial satellite intelligence has become increasingly prevalent, shaping military strategies and informing public discourse. However, the availability of such data also raises serious legal and ethical questions about access and control. Commercial satellite data providers must thread a delicate balance between information sharing (in the name of neutrality and transparency) and the national security concerns of their clients.

Due to the low cost of entry and access to space infrastructure, commercial space actors have begun to play an increasingly important role in this landscape. They face, however, their own set of challenges including responsible management of space-based data and signals, resilience of their space assets, reliability of data processing, storage, and analysis, and lastly balancing of security and privacy. The business model of private satellite providers necessitates navigating competing interests, including information sharing with media and humanitarian organizations while remaining reliable partners to governments intent on keeping information about capabilities, developments on the ground, tank positions, and troop movements highly classified. In short, commercial entities must weigh economic benefits with social benefits and reconcile the private ownership of public-good data with national security concerns and potential geopolitical ramifications.

The notable benefits of the growth and availability of satellite data cannot be underestimated. Outer space proved vital to the management of pandemics, natural disasters, agricultural outputs, and monitoring of wars. Legal restrictions, such as the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment (KBA), however, can also significantly complicate the information-sharing landscape by limiting the release of up-to-date high-resolution satellite imagery in certain contexts. In 2022, Maxar Technologies’ release of satellite imagery showing Russian troop build-up along Ukraine’s border proved invaluable in dispelling disinformation. But according to reports by Scientific American, private companies including Planet Labs and Maxar Technologies have restricted or delayed high-resolution optical satellite imagery by 30 days in the Israeli siege of Gaza citing “potential for misuse and abuse.”

Private actors must thus increasingly reckon with the unintended consequences of detailed satellite ad hoc data sharing in active conflict zones in high-demand data environments. Navigating these complexities will require international cooperation, technological innovation, and a careful consideration of ethical and political implications as well as the provision of legal guardrails to avoid the appearance of bias and undue politicization.

Developing suitable legal instruments to address the fundamental challenges of armed conflict in outer space is essential and long overdue. This endeavor and US leadership are not only crucial in addressing the challenges raised above and establishing overarching principles of international law applicable to activities beyond Earth, but they are also key to the expansion of the scope of existing institutional mechanisms to arbitrate legal disputes between both state and non-state actors involved in the space arms race, surveillance, and reconnaissance while fostering a functional framework for space diplomacy.

Dr. Joanna Rozpedowski is a non-resident senior fellow at the Center for International Policy and an Adjunct Professor at George Mason University, Schar School of Policy and Government. Twitter @JKRozpedowski

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.