Contemporary Indian foreign policy has its share of detractors, and with a superficial look at India’s actions, justifiably so. Naturally, some sections of the international community believe India’s stance on the Ukraine war and the recent squabble with Ottawa are examples of Delhi’s self-centered approach. Such arguments reflect the growing conjecture that India does not care enough for values and is an interests-only power.

In this context, we would do well to step back and revisit this principle– that countries, irrespective of the rhetoric espoused, function based on their interests.

To rewind to the postwar period, the United States emerged as one of the global superpowers after the defeat of the Axis powers in the Second World War. Unlike its wartime ally, the Soviet Union, German tanks had not battered the US army. Moreover, compared to its beleaguered West European peers– Washington’s position was undeniably preferable. From this vantage point of pre-eminence, the US carefully built the “rules-based” international order. In effect, the rules of the order flowed from the reservoir of US power.

Given the necessity of building a stable order, American officials and diplomats intuitively understood that pursuing self-interest at the cost of others would generate resentment. Such resentment would repeat the horror cycle of the previous decades.

Therefore, Washington encouraged economic growth in Germany and Japan. The primary motive was to defang the snake of postwar animosity. Ideas of free trade, liberalism and economic reconstruction impregnated the new American order. Washington’s message to Berlin and Tokyo was straightforward: chase prosperity, rebuild your economies, but play within our order. Sapped by the doldrums of persistent conflict, the Axis partners readily acquiesced.

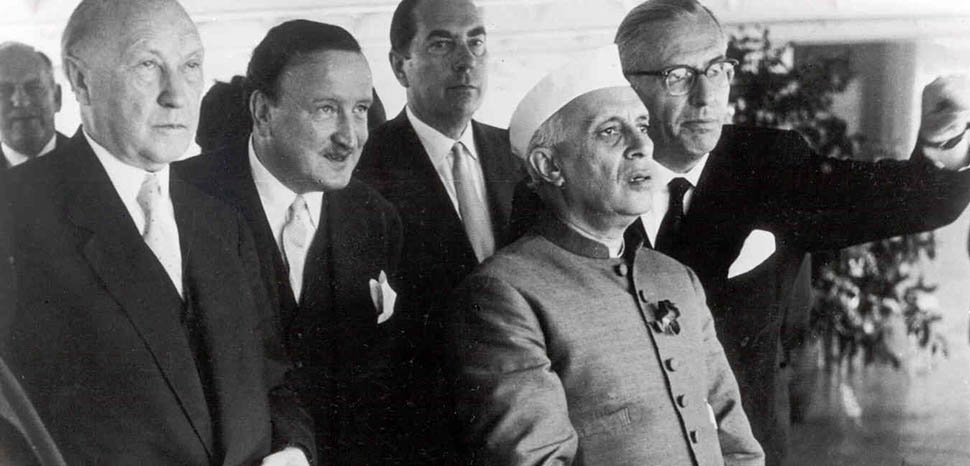

During this period, India underwent an identity rejig. Independence from the British in 1947 meant the fetters of political overlordship were unshackled. Drinking from the goblets of freedom, the Indian leadership believed Delhi’s time had come. With his gift of the gab, Nehru frequently held forth about India’s position among the rule-makers of the world. No matter impoverishment and scarcity, India’s history as a civilization made it a great power, believed Nehru.

In the 1950s, hectoring the West about hypocrisy and double standards was one of the recourses of India’s external policy. Colonial enterprise, rapid nuclear armament, and dividing the world into spheres of influence were the routine accusations that emerged from the Indian discourse about values and principles. However, given the dearth of Delhi’s material capabilities, Western policymakers paid scant attention to Delhi’s moralizing. It was a case of an empty vessel making more noise.

In the 1960s, the realities of war struck Delhi. Two wars with its neighbors, first with China and later Pakistan, punctured the romantic notions of Delhi’s “manifest destiny” in the comity of nations. The Anglo-American penchant for Pakistan also concerned Delhi. The natural course of action was to cement ties with the Soviet Union. Consequently, till the end of the Cold War, partnership with Moscow remained the overpowering doctrine of Indian foreign policy.

Since then, India has reimposed faith in doing the boring things that take one far. Actions like growing the economy, calling for more arms production at home, and diversifying its external partners. Consequently, the last three decades have produced a linear flow in India’s foreign policy. In the same spirit, capitalizing on natural equities in the Anglosphere countries is, and will remain, one of Delhi’s priorities.

Even after the decent showing for the last three decades, India still has mountains to climb. Compared to China’s economic pie of $14 trillion, India still lags behind at around $3 trillion. In other words, India is in the phase of building capabilities. However, building a robust economy is difficult in India’s neighborhood. With two colluding neighbors with nuclear weapons breathing down one’s neck, the scenario of security threats going out of control remains ever-present.

In this security landscape, India has limited choice but to focus on its interests in building material capabilities which flow from a powerful economy. Naturally, India’s foreign policy choices also originate from this desire. Taking a nuanced position vis-a-vis the war in Europe and refuting Canada’s claims stems from keeping away maladies that may infect India’s economic pursuits. Ignoring relations with Russia could imperil India’s arms inventory that rely on Russian spare parts and maintenance, and going soft on issues of terrorism risks domestic stability.

History shows that to make principles count, India needs power. Without that, no amount of beating the drum– about values and principles– will preserve order. It will be mere noise.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.