With regard to international diplomacy of the hour, the 78th Session of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly General Debate is where it’s at. This yearly highlight of multilateralism, which draws world leaders together to shine a light on and debate solutions for important issues of the day, is just about to be in the international community’s rear-view.

Yet—first, in the context of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) group’s landmark XV Summit and, second, in the manner of the BRICS membership’s outsized role regarding the G20 summit held thereafter—another consequential diplomatic moment only recently garnered the international community’s attention.

This BRICS moment, as it were, is revealing of the fact that the interests of two principal sub-groupings therein seemingly cut in opposite directions, even as there is some confluence of thinking on the Ukraine war.

Insofar as they are locked in great-power competition—which has once again eclipsed great-power engagement—with the United States, “America’s strategic competitors” à la the BRICS group stand at one geopolitical pole. Notably, Russian President Vladimir Putin and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) President Xi Jinping have committed to a ‘no limits’ bilateral partnership.

Their respective U.S./Western-directed foreign policies are sharply confrontational, pointing to a break from the goodwill-cum-trust generated by the Clinton-Yeltsin entente (in the case of Russian-U.S. relations in the earliest days of the post-Cold War era) and the Nixon-Mao-driven—Kissinger-orchestrated—rapprochement (in the case of Sino-U.S. relations in the period of the ‘opening of China’ in the 1970s).

Taken together, these cases heralded a new age of great-power engagement.

With the foregoing in mind, it is useful to glimpse back in time; in particular, casting our gaze to the period of transition on the cusp of the aforesaid entente. As the United Kingdom’s Second World War leader and statesman extraordinaire, the late Winston Churchill, famously said: “The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.”

For our purposes, the Cold War’s end is of interest. Instructively, great-power engagement was the hallmark of that geopolitical transition that played out just over three decades ago.

The idea that a geopolitical windfall, or, at the very least, security-related dividends will (likely) emerge from that type of sustained, high-level engagement especially rings true in the historical reality in question.

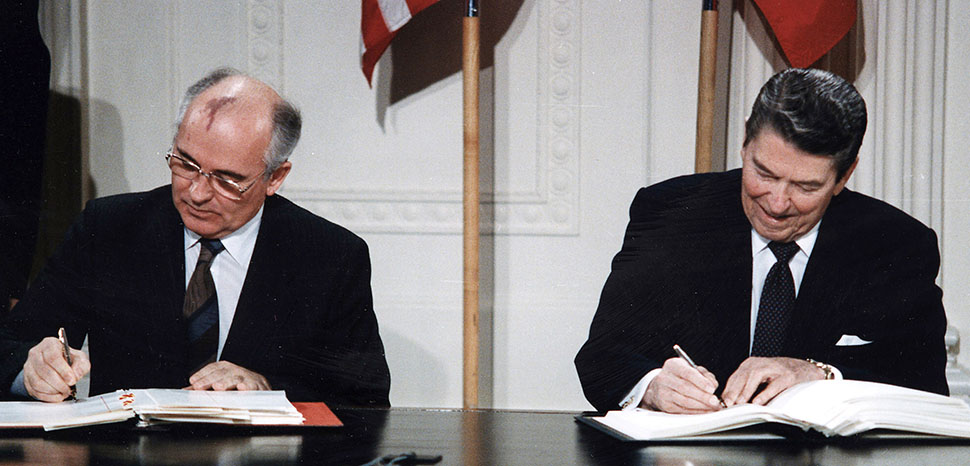

On account of a set of final negotiated steps—as illustrated below—the Cold War came to a “peaceful end,” which the international politics fraternity failed to predict.

As it pertains to the post-Cold War Russian-U.S. relational axis, that engagement collapsed in on itself, and the so-called Putinisation of Russia is particularly telling.

As it pertains to the post-Cold War Russian-U.S. relational axis, that engagement collapsed in on itself, and the so-called Putinisation of Russia is particularly telling.

With regard to the Sino-U.S. relational axis, it was a decades-long, productive engagement—a highlight of which was the PRC’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001.

In the 2000s, great-power relations began to breakdown. Ultimately, they took a turn for the worse. Brinkmanship over hot button issues continues to unsettle the geopolitical landscape, sharpening divisions between adversaries. (Yet, their fraught relationship notwithstanding, the PRC and the U.S. need each other, as the world needs them to keep their cooperation even-keeled.)

Those relations, which reverberate at the level of the global security architecture, soured. The common geopolitical denominator: Worsening relations with Washington come into play in a system-level context where the United States and Russia are going toe-to-toe in their confrontation with each other, with the PRC running interference for its junior partner.

However, India, an Asian regional power—on account of the PRC’s geopolitical designs in the Indo-Pacific—is deepening security ties with the United States. Yet, New Delhi underlines its neutrality in respect of the Ukraine war. Notwithstanding its hand-wringing, New Delhi makes no bones about its close relations with the Kremlin. Both of New Delhi’s above-stated positions are an outgrowth of “its concerns vis-à-vis China and Pakistan,” as well as its desire to keep the Kremlin in check in respect of further deepening of Russia’s bilateral relations with each of them.

While early in the Biden Administration’s first term in office Brasília signalled that it was eyeing a new era in Brazil’s relations with the United States, in the period since, there has been a sharp change in tone. This South American powerhouse has taken to bashing American hegemony, all while pressing for a Brazilian peace plan as regards the Ukraine war that has not been well received by Kyiv. Stating plainly, it has raised the ire of both Kyiv and its backers. As expected, regarding this turn of events, Brazil hands have expressed grave consternation.

Meanwhile, in several quarters, South Africa’s hand in what is widely seen as a bungled African peace mission earlier this year to Russia and Ukraine vis-à-vis the Ukraine war continues to come under fire. Washington remains especially vocal about Pretoria’s “close ties with Moscow,” which run deep, casting doubts about South Africa’s purported neutrality in respect of the Ukraine war.

These latter three countries (i.e. middle powers) are in the captioned second (catch-all) sub-group, for whom the Ukraine war also features frontally in foreign policy calculus.

In line with their respective national interests, with an eye to the first sub-group’s respective actors (i.e. major powers), they play off how they diplomatically angle on the matter.

That said, for the reasons outlined above, India is invested in strong ties with the United States and the West. Beyond this, the importance of U.S.-India economic ties cannot be overstated. The same applies for U.S.-Brazil and U.S.-South Africa relations.

But the other side of the coin is that no matter how one slices it, the BRICS group has been instrumentalized vis-à-vis the Ukraine war.

In sum, seemingly overpowering qua displacing the group’s standard-fare narratives, this war is the elephant in the ‘BRICS (diplomatic) room’.

A lot of the oxygen in the group is now taken up with such geopolitical power plays which—irrespective of respective BRICS members’ geopolitical dances with the United States—are a common thread within the group.

What is more, the principal drivers of strategic competition, which the late historian Eric J. Hobsbawm referred to as ‘political forces’ in the shaping of epochs, are racing against one another to win over backers in the Global South—i.e. ‘the rest’.

By the looks of things, even as the Ukraine war is weighing on Western leaders’ hearts and minds, it has seemingly been an uphill struggle for Western foreign and security policy communities to get many Global South decision makers and foreign policy representatives/hands to view and prioritize the conflict in the way that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and his Western backers are framing it.

Rightly, UN Secretary-General António Guterres underscores that Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine “is aggravating geopolitical tensions and divisions, threatening regional stability, increasing the nuclear threat, and creating deep fissures in our increasingly multipolar world.”

The world is in the throes of a multipolar international order in the making, proximate to a new Cold War with wars of attrition—such as the Ukraine war—likely being the first in a chain of conflict and wider insecurity in international relations. (This stands in stark contrast with the post-Cold War-related transition.)

As great-power competition casts an ever longer shadow in that regard, the wider security-related implications have seemingly not yet caught on as widely as Washington and Kyiv—along with their backers—had once hoped.

Moreover, in these high-stakes geopolitical manoeuvres of the moment, the Kremlin’s Ukrainian gambit has the makings of a two-for-one (sucker) punch. In short, it has run roughshod over the European security architecture—as expected, violating UN-underwritten norms and rules of the road—all while muddying the waters still further as regards the Global North’s relations with ‘the rest’.

Adding to the air of geopolitical uncertainty, one consequential, anti-Western spoiler has pulled back from a prime dimension of its relations with the United States.

Such episodes of high politics are a window into how great-power engagement—aspects of which, in a bygone era, were once extolled by Reagan and Gorbachev—is now on the losing end of a test of geopolitical wills, whose proverbial currency of power is hewed more than ever to grievance against the U.S./West.

This in an age where—for the West, at least—the combination of recalcitrant, emergent powers and an increasingly assertive patchwork of Global South actors in geopolitical play make for a more risky, less familiar coming international order, which in Churchillian terms may well “open a quarrel between the past and the present.”

Churchill’s assessment of what this type of quarrel portends for the future is grim, indeed.

In this moment, then, yet another one of Churchill’s many bits of sage advice also resonates with students of International Relations: “Study history, study history. In history lies all the secrets of statecraft.”

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The author would like to thank Ambassador Riyad Insanally for his generous and insightful advice on an early version of this article, as well as his engaged commentary on related work. Special thanks to Ambassador David Hales for perusing an earlier draft of this article and for wide-ranging discourse, which shaped the author’s perspective on underlying themes. The author is especially grateful to Ambassador Patrick I. Gomes for his incisive feedback, openness and encouragement regarding his scholarship, which also benefits from Ambassador Colin Granderson’s input.