Summary

Afghanistan is known as the graveyard of empires for a reason.

Occupying prime geopolitical real estate as a land bridge between Europe and Asia, the country has figured into continental trade routes for as long as humans have been trading. This geography is still highly relevant today, evident in the regional trade schemes lining up to incorporate Afghanistan: China’s Belt and Road (BRI), India’s International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), and the Lapis Lazuli corridor to name a few.

Now that the United States is heading for the exits, Afghanistan will once again become a coveted piece on the geopolitical chessboard of regional heavyweights. This series will examine their goals and motivations. It starts with Pakistan, a country that managed to maintain an influential role throughout the ebbs and flows of the NATO campaign, albeit potentially at serious economic cost in the years to come.

Background

Navigating the strategic depths

It was the India-Pakistan security dynamic that dominated Afghanistan’s interactions with its immediate neighbors in the period from the Soviet withdrawal to the US invasion in 2001.

The Pakistan security establishment has long favored the doctrine of “strategic depth” with regard to Afghanistan. Put simply, the policy seeks to ensure that a friendly government is in place at all times. If that can’t be done, then Pakistan will maintain close ties with sympathetic militant groups in order to ensure a high degree of leverage against the government in power. The most obvious example of strategic depth in action is the Inter-Services Intelligence’s (ISI) and army’s longstanding relationships with militant outfits like the Taliban and Haqqani network.

The ultimate aim of strategic depth is to avoid the advent of an India-aligned government in Kabul, a development that could threaten Pakistan with the nightmare prospect of a two-front war with India. Indeed, much of Pakistan’s foreign policy calculation is based on planning for a war with India, likely centered on Kashmir. The two countries fought a series of limited battles in the disputed territory as recently as 1999 in a conflict known as the Kargil War.

Unfinished business of the Durand Line

Yet there’s another reason for Pakistan to be particularly attentive to Afghan domestic politics. The Durand Line separating Afghanistan and Pakistan is, like many colonial-era borders, an arbitrary and flawed division that cleaved ethnic communities into two. The cleavage impacted Pashtun and Balochs in particular. Both ended up on opposing sides of an international border that materialized out of nowhere with a stroke of a British pen. This division informed the ethnic makeup of the resulting states, depriving the Pashtuns of their historical numerical superiority over Afghanistan’s other ethnic groups. It also left Pakistan with millions of Pashtuns who were more culturally, linguistically, and historically aligned with their brethren in Afghanistan than the Urdu-speaking mainstream in Karachi.

The Durand Line has still not been recognized by Afghanistan, and according to former president Hamid Karzai – it never will be. The border dispute poisoned AfPak relations for decades after World War II. In 1947, Afghanistan’s ambassador refused to vote for Pakistan’s admission to the United nations. And the two states teetered on the brink of war through much of the 1970s amid a resurgence of cross-border Pashtun nationalism. But the Soviet invasion of 1979 would bring about a fundamental change to bilateral relations, pitting Pashtuns on both sides of the border against the USSR-backed government in Kabul. Thereafter it was political Islam more so than ethnicity that framed Pashtun identity. And some 15 years later, this radical strain of political Islam would manifest in some of the more extreme Taliban policies.

Herein lies another reason for ISI support of the Afghan Taliban: so long as they’re on-side, they won’t stir up cross-border Pashtun nationalism and threaten the integrity of the Pakistani state. This vulnerability also makes Indian inroads into Afghanistan all the more menacing in the eyes of the security establishment, since in the event of a conflict, New Delhi could incite Pashtun nationalist groups and divide the attentions of Pakistan’s military planners.

Shifting AfPak trade dynamics

Rich in minerals, water, and potential electricity generation, the Afghan economy has been punching below its weight for decades now. In some ways this lack of development and paucity of trade routes has actually benefited Pakistan, which held considerable leverage over land-locked Afghanistan by virtue of geography. This dependence has helped Pakistan remain one of Afghanistan’s major trading partners, sending wheat, rice, sugar, cement, and other products across the border. In 2017, Pakistan exported some $1.68 billion to Afghanistan – just shy of the $1.94 billion it exported to China. However, unlike China, Afghanistan exports a mere $406 million to Pakistan, resulting in a much-needed surplus for Islamabad. Any surplus is welcome news given Pakistan’s yawning trade imbalance (a $16.8 billion deficit from July-December 2018 at last count).

In a worrying sign for Islamabad, the prevailing AfPak trade dynamic is changing. Bilateral trade has been trending downward over the past few years, and it seems to have fallen off a cliff in FY2018. Plummeting bilateral trade is driven by two factors: the opening of new trade routes (air corridors with India, Iran’s Chabahar and Bandar-e-Abbas ports, for example), and a shrinking appetite for Pakistani products.

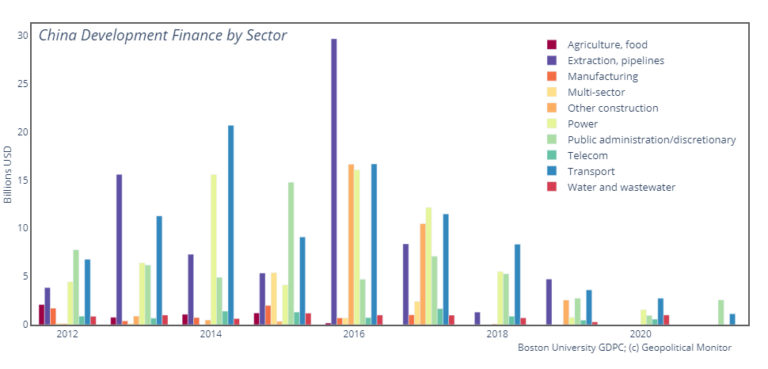

Afghanistan has always occupied some prime geopolitical real estate at the crossroads of South and Central Asia, and this position has made it a coveted partner in various infrastructure projects linking Europe and Asia. Iran’s Chabahar port is enabling Afghan-Indian trade that completely bypasses Pakistan (interestingly, the port has also been exempted from the Trump administration’s sanctions, apparently at India’s request). Afghanistan is also the opening leg of the Lapis-Lazuli transport corridor, a Europe-Asia trade route linking Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. Again, this corridor bypasses Pakistan. And finally, Beijing is hoping to expand the $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) into Afghanistan via Peshawar. Though this is one plan that wouldn’t bypass Pakistan, it could be expected to flood the Afghan market with made-in-China products, much to the detriment of Pakistan’s own exports.

It would appear as though the good old days of being the only alternative for trade are over for Islamabad, and Afghan-bound trade from Pakistan will continue to trend downward in the near future.

In search of a US-Pakistan ‘reset’

For the vast majority of NATO’s 17-year involvement in Afghanistan, the Taliban have been viewed as an organization that must be, if not eliminated entirely on the battlefield, then at least marginalized to the point of exclusion from the Afghan political process. More recently, however, as it became crystal clear that a military solution is unrealistic, US officials have come around on the idea that the Taliban can be a legitimate political actor in the post-war order.

The evolution of US perceptions toward the Taliban traces the arc of US-Pakistan relations over the same period. Islamabad has continued supporting the Taliban through the entirety of the conflict; if not always directly, then indirectly by providing safe havens along the AfPak border. To be fair, these safe havens are not always the direct result of policy decisions by the civilian government or even the security establishment. As outlined above, the AfPak borderlands are inhabited by similar cultural groups who are happy to offer sanctuary to their tribesmen across the border.

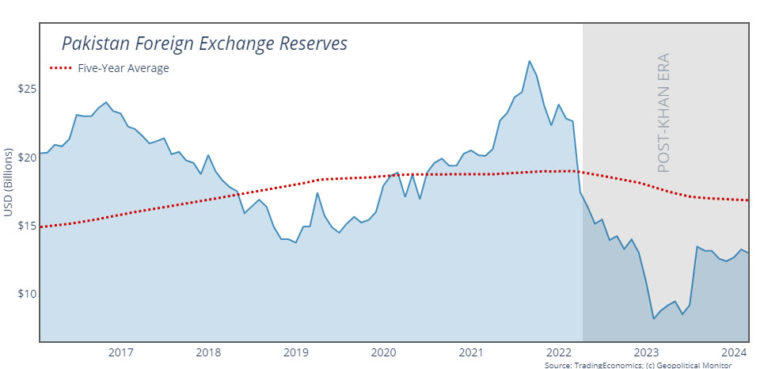

Unsurprisingly, Pakistan’s laissez-faire attitude toward the Taliban has been a sticking point in bilateral relations with the United States. The Obama administration tried to force Islamabad to cut ties with Afghanistan-based militant organizations by cutting off official assistance. From 2010-2017, US military aid to Pakistan dropped some 60%. Yet Islamabad has continually refused to alter its behavior. Not only that, alternative foreign patrons have stepped in to fill the void of US aid, namely Russia and China.

If the past eight years have proven anything, it’s that the United States is not the indispensable ally it thought it was.

Fast-forward to the present and the Taliban has been rehabilitated, in branding if not deeds. Now Pakistan is recast from self-interested troublemaker to indispensable middle-man: Islamabad is the only party who could hypothetically convince the Taliban to ‘play ball’ in the new political system. These new circumstances have elicited a predictable about-face in US policy toward Pakistan, with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo pledging to “reset” bilateral relations when he met Prime Minister Imran Khan in September of last year.

Thus, having demonstrated a willingness to diverge from US dictates over the past 17 years, Islamabad and the Pakistan security establishment will not be changing their policy toward the Taliban now that a semblance of victory is close at hand. Pakistan’s stance toward Afghanistan’s militant groups will continue to be guided by the two overriding goals of forestalling new inroads by India and preempting the growth of Pashtun nationalism – even if these goals come at the expense of rebuilding relations with Washington.