Summary

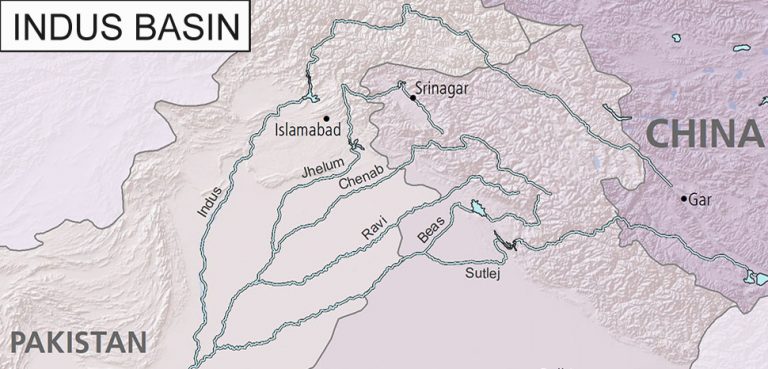

Many of the world’s most iconic river systems – the Mekong, Indus, Yangtze – are fed by glaciers that both supply and modulate their water flow. Now these glaciers are melting due to climate change, threatening irrigation systems, electricity generation, and drinking water reserves in some of the most densely populated areas of the planet.

No two glaciers are exactly the same. They’re melting at different rates, with some entering their terminal decline sooner than others. The repercussions vary as well. In some cases, reductions in glacier runoff have a negligible effect on downstream flow. In others, they can severely disrupt local water systems, particularly those with antiquated and wasteful extraction methods.

The concept of ‘peak water’ is key to understanding glacier decline. As overall glacier mass shrinks, higher-than-average run-off is produced during the melt season. However, these run-off levels will eventually peak, and a period of terminal – and essentially irreversible – decline will follow. Every glacier has a unique peak water threshold. According to a study published by Nature Climate Change, around 45% of the world’s glacier-fed basins have already passed this point, including the source of the Brahmaputra. Another 22% of basins are predicted to be trending up in run-off through to 2050, including the Indus and Ganges headwaters, which are expected to peak in 2070 and 2050 respectively.

The threat of glacier melt is difficult to assess in isolation. Water systems across the globe are already being taxed by other stressors such as dam construction, irrigation, and extraction for municipal or industrial use. It’s widely accepted that glacier melt will exacerbate these problems, albeit to differing degrees.

This new series will examine some of the world’s most vulnerable glacier-fed water systems, beginning with Kazakhstan’s Lake Balkhash basin, and how changing ecosystems risk international water conflicts among the states that rely on them.