Summary

Chabahar is an Iranian port located on the Gulf of Oman. Originally built in 1983 in order to diversify trade away from the Persian Gulf during the Iraq war, Chabahar port was recently expanded following some $500 million in investments and loans from the Indian government. The site consists of two separate ports, Shahid Kalantari and Shahid Beheshti, which combined have ten deep-water berths.

But Chabahar is more than just a port; it’s a coming out party for India’s regional trade ambitions, the first real attempt at a Belt and Road with Indian characteristics. The port, along with the $1.6 billion Chabahar-Zahedan railway link to Afghanistan that connects to it, seeks to solidify new regional trade routes to Central Asia, routes that will in some cases compete directly with China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) Initiative, particularly the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Chabahar port also figures in India’s more ambitious North-South Transportation Corridor, a rail/road/maritime connectivity project that runs northward through Central Asia, Russia, and eventually Europe.

This backgrounder will examine what Chabahar port represents for the main players involved. It will also explore whether or not India’s plans will be jeopardized by President Trump’s recent exit from the Iran nuclear deal.

Background

India

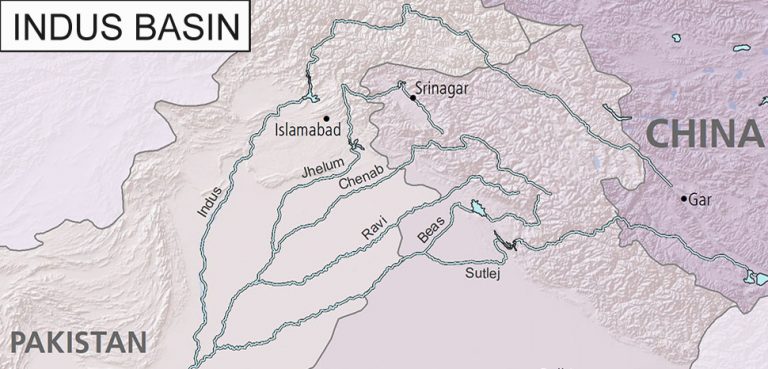

New Delhi is the primary financial and diplomatic backer of the Chabahar port, and it is the country that stands to gain the most from its operations apart from Iran. The port helps to alleviate the central impediment of India’s present geography: its lack of a direct land link to Afghanistan (and by extension Central Asia), which is cut off by Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Indian policy planners were concerned about the possibility of being excluded from new major trade corridors like CPEC, which would proceed northward from the Pakistani port of Gwadar and then into Central Asia via China’s northwest, completely bypassing India and diverting trade away from Indian ports. Their solution was to establish an alternative corridor, one that begins with a seaborne leg between India’s Kandla port and Iran’s Chabahar, a distance of just 550 nautical miles. From there trade will proceed northward to Afghanistan and beyond to Central Asia and eventually Europe.

In the works since 2013, phase one of the new expansion of Chabahar port opened for business in late 2017. The port is the result of a trilateral deal between Iran, India, and Afghanistan. In February 2018, another deal was signed for India’s state-owned Ports Global Limited to lease and operate phase one of Chabahar (Shahid Beheshti) for 18 months. The agreement to run an overseas port represents the first of its kind for an Indian state-owned operator.

New trade links with Central Asia may be the medium-term goal, but Chabahar will pay off short-term by deepening India’s influence in Afghanistan. Indeed, Indian wheat has already started to flow through Chabahar and into Afghan markets. And there’s a lot of room for growth here: India exported just $560 million worth of goods to Afghanistan in 2015.

India will soon gain access to four of Afghanistan’s largest urban markets: Herat, Kabul, Mazar-e-Sharif, and Kandahar. India has been making aggressive moves to penetrate the Afghan market, particularly in Kabul where Pakistan has lost an estimated 50 percent share of the local market this year alone.

Afghanistan

Any regional issue that brings India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan to the same table will inevitably be influenced by the underlying geopolitical tensions between the three countries. Pakistan’s longstanding “strategic depth” approach to Afghanistan seeks to preclude the country becoming too close to New Delhi, a development it fears could usher in the possibility of a two-front war. Strategic depth in practice translates into Pakistani support for various paramilitary groups within Afghanistan, often to the detriment of state stability. Despite a general proximity and the absence of any major bilateral disputes, India-Afghanistan relations have often been thwarted by geography given their lack of a land connection and Afghanistan’s historical reliance on Pakistan’s ports. Chabahar of course could put an end to this dynamic, making it a potential game-changer in the Pakistan-India-Afghanistan triangular relationship.

The appeal of Chabahar port to Kabul is largely in that it will allow for trade diversification away from its present overreliance on Pakistan’s ports. Afghanistan is a landlocked country and Pakistan, particularly the port of Karachi, has historically served as its maritime gateway to global markets. In the past, Pakistan has sought to benefit from its neighbor’s dependence by throwing up tariffs, randomly shutting down border crossings, and thickening the bureaucratic red tape at Pakistani ports in order to limit Afghan exports and extract diplomatic concessions.

Kabul has long resented this overreliance on Pakistan and has been actively seeking to escape from it. Recently its efforts have begun to bear fruit, particularly with regard to Iran’s Chabahar and Bandar-e-Abbas ports. Together these ports have diverted a considerable amount of Afghan trade away from Pakistan: bilateral trade volume has shrunk to just $500 million from a high of $2.7 billion a few years ago.

Iran

There are obvious economic benefits in Iran establishing itself at the heart of a new economic corridor spanning the Middle East and Eurasia. The country occupies some prime geography for both One Belt One Road (OBOR) and India’s North-South Transportation Corridor. Iran is also desperately in need of foreign investment and new domestic infrastructure projects after years of biting Western sanctions.

With regards to the Chabahar port, Tehran mostly wants to maintain its own relevancy vis-à-vis Pakistan’s Gwadar port, which is just 80 km away and a central piece of China’s world-straddling One Belt One Road plan. Like India, the Iranian government is worried about being elbowed out of new global trade corridors that bypass its territory. However, unlike India, Iran isn’t angling to unravel or balance China’s ambitions in the region; this is a question of economics, not realpolitik. Iran’s geopolitical ambivalence was on open display in its invitation earlier this year for China to join the Chabahar project, reportedly after internal misgivings about the pace of construction for the second phase of the port (Shahid Kalantari).

The prospect of new U.S. sanctions against Iran is a limiting factor in the progress of phase two, but it will be hard to know just how much of one until the dust settles from the recent US pullout from the Iran nuclear deal. As it stands now, financing could be impacted as banks pull out of the project. According to Dawn, at least three infrastructure contracts have been delayed as the companies behind them seek clarification over whether or not the new sanctions will apply.

Pakistan

Pakistan has the most to lose from the Chabahar port project in terms of diverted trade flows and lost influence over Afghanistan. Even with Chabahar operating well below its full capacity, some 80% of Afghan cargo traffic has already been shifted from Karachi to Iran’s Bandar Abbas and Chabahar ports. The amount of cargo running through Chabahar is expected to increase in stride with increased connectivity along the North-South Transport Corridor.

As trade with China has surged with the CPEC corridor, trade with Afghanistan has increasingly been diverted toward Chabahar port. Yet for Pakistan, the benefits haven’t necessarily balanced out the drawbacks. Pakistan’s trade relationship with China is characterized by a deep trade deficit that has only widened since the two countries signed the China-Pakistan Free Trade Agreement (CPFTA) in 2006. From 2005-2017, Pakistan’s exports to China grew from $0.4 billion to $1.7 billion USD. Over the same period, imports from China increased from $1.8 billion to $13.9 billion. As CPEC trade flourishes, the Sino-Pakistan trade deficit yawns and Pakistan’s foreign reserves dry up. In contrast, Afghanistan represents a market that actually wants what Pakistan is selling. In 2010, Pakistan’s exports were valued at $2.4 billion. By 2017, that number was down to $1.39 billion, and it’s expected to fall even further as Chabahar ramps up its operations.