In 1794, during the last wave of Terror in revolutionary France, Maximilian Robespierre decided to jail his opponents, in sequence, on the radical and moderate sides of his political spectrum. He aimed at having a ‘balanced’ approach against those he considered were supporters of public corruption on the right and saboteurs of change at the left.

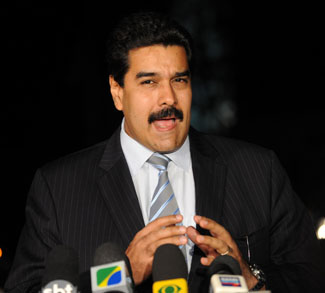

A few days ago, shortly after a well-publicized international business conference in Riyadh having the presence of key operators of the Western financial and investor establishment, the Saudi Crown Prince ordered the arrest of some of the most well-known businessmen in the country. The detainees come from a wide range of viewpoints within the business and ideological (i.e. religious) Saudi elite, so it may be worthwhile describing a few of them that I once knew: a prince, among the wealthiest individuals in the world, who in front of his office desk has a wide tall column with dozens of TV sets (unlike in an electrical appliance shop, each set switched on a different channel) and is surrounded by an office entourage that includes, in the heart of the puritanical Saudi capital, attractive female assistants walking in not so prudish outfits; a veteran real estate developer, notorious for some old business difficulties, but nowadays considered a pious supporter of charitable and other religious causes (and having a mansion with an entrance corridor guarded by standing elephant tusks decorated with gold); a respected (at least until recent times) technocrat with recognized governmental experience in financial affairs; and the head of the largest construction group in the country, a company that, despite its ominous name, has been the main beneficiary of the infrastructure and palace building construction contracts awarded by the Saudi monarchy for decades.

Historically, the vast majority of the Saudi population has not been able or willing to do paid physical work and this is a fundamental crack, as no country can function if everybody aspires to a desk job.

Although the Saudi seizures were not done sequentially, it can be argued that the approach follows Robespierre’s script. Beyond this and, quite sadly, a like for human decapitations in public, the similarities between revolutionary France and the present Saudi regime seem to end.

The stunned reaction from the world media to these high-profile detentions is an unhelpful distraction from more important issues confronting Saudi Arabia. These arrests only reflect a particular (although crucial) conflict within the Saudi establishment. While the blitz has been justified as an effort against corruption, the clear targeting of some of the largest fortunes in the country seems also to have in mind the control of this wealth at times when Saudi Arabia faces increasing financial difficulties. The adverse world oil price situation and the large financial commitments in the Yemeni war are putting significant strains on the country’s pockets and no doubt can derail any serious effort toward modernization, the country’s latest social initiative. Complicating matters, it is worth remembering that the Saudi royal family is among the largest in the world, with dozens of ambitious princes in perennial search for dominance and further wealth.

The different tribal forces at work also need to be considered. A wise Saudi told me once that the pecking order of loyalties in his land are: tribe, religion, and lastly the country. The vast territory named, with geographical ignorance but without irony, Arabia Felix in Ancient Rome, was finally unified under the hegemony of the Al Saud tribe after bloody wars that alienated and displaced other strong clans. It is a well-known secret in Saudi Arabia the nostalgia and longing for power that these events still stir in the minds of the new generations within the losing tribes.

On matters of faith, the religious establishment still has deep influence across society. The Al Wahhab-Al Saud political coalition forged in the mid-1700s seems to be intact and is the biggest challenge to any serious efforts to bring Saudi Arabia into the 21st century. It is surprising (or perhaps not) that some prominent business names associated with financial support to radical Islam were not included in the recent purge. And beyond the intra-Sunni conflicts, the Shi’a population, concentrated in the oil rich part of the country, is a perennial threat to its stability, particularly given Iran’s growing assertiveness.

Internationally, Iran of course represents the largest peril to the survival of Saudi Arabia. But characterizing the Saudi-Iran rivalry as a religious conflict severely underestimates the deep geopolitical roots of this centuries-old contest. The struggle between the Arabian nomadic tribes and civilized Persia was a live conflict even before the advent of Islam. The entrance of Persia into Islam only exacerbated old tensions, as illustrated by the long struggle between the Umayyads and the Abbasids across the Muslim world in the Middle Age.

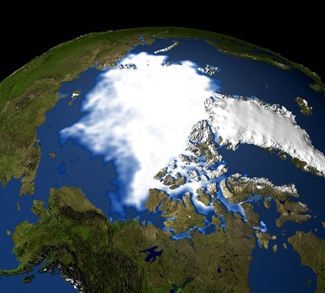

Against this backdrop of domestic and external trials, Saudi Arabia’s current efforts at social change need to be put in context. The most visible part of Vision 2030, Saudi’s strategic blueprint for change, is a $500 billion mega-city project intending to spearhead economic growth through technological innovation. In parallel, the government wants to gradually end the vast array of subsidies that has kept the large and fast growing Saudi population at peace for a long time. This increasing population is in itself another challenge and justifies dismissing any comparison with similar modernization efforts in the smaller Sunni monarchies of the Persian Gulf.

A cultural connection also needs to be made. Historically, the vast majority of the Saudi population has not been able or willing to do paid physical work and this is a fundamental crack, as no country can function if everybody aspires to a desk job. To make up for this deficiency, the Saudi economy depends on cheap imported labor coming predominantly from the Indian sub-continent. The potential destabilizing consequences of such a large foreign population of modern day sans-culottes cannot be dismissed given their endemic mistreatment which, unfortunately, is a deeply ingrained behavior; Saudi slavery was abolished only in 1962, and we all know from old American enslavement and Russian serfdom how long it took for a full eradication in the mindset of this human disgrace.

From a financial view point, Saudi ambitions have made inevitable the partial sale of the country’s oil assets to foreigners through the planned privatization of Aramco, the world’s largest oil producer. This financial gunpowder may also be needed to prevent social upheaval if austerity backfires.

Revolutions from the top are only successful if the leadership manages to unleash forces that already exist in society and are seeking change. This applies to Saudi Arabia and also to old similar efforts like the ones of Peter the Great and Ataturk. There seems to be a genuine desire for social transformation in some segments of the Saudi middle and upper classes, but there are also deep forces across the entire society resisting social transformation. Who will win this battle remains to be seen.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.