Late on the evening of August 16, three female suicide bombers set off a series of explosions that left at least 27 people dead in Nigeria’s Borno state, a stronghold of Boko Haram. The first attacker blew herself up near a refugee camp, triggering a panic. In the ensuing chaos, the second and third attackers detonated their own devices, claiming most of the casualties. Two days prior, on August 14, gunmen attacked a United Nations peacekeeping mission in Timbuktu, in northern Mali, killing seven. On the same day, in neighboring Burkina Faso, gunmen killed 18 people eating dinner on the terrace of a local cafe, several of whom were foreign nationals.

This sobering burst of violence in West Africa and the Sahel is a vivid reminder of a threat that’s often forgotten.

Indeed, terrorism across sub-Saharan Africa is not a small or diminishing problem. Quite the opposite: the terror threat on the continent has metastasized. There now exist multiple epicenters, spanning the vast, ungovernable territories of West Africa and the Sahel, each harboring its own distinct groups with their own distinct agendas. But while some groups may differ in their motivations, they each share an important common denominator: they are the beneficiaries of poor state capacity, i.e. they exist where the state’s remit is weakest.

Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, state power and authority tends to diminish as the distance from capital cities and large urban centers increases. It is in these hinterlands where sparse government authority has sown destabilization for decades. This poses a distinct problem for African governments and Western states alike. For as destabilization spreads, so too do the number of potential havens for extremist groups to hide, scheme, and launch attacks unhindered, resulting in further destabilization. This cycle threatens to transform localized crises into regional ones in a positive feedback loop that few can afford.

Here are some of the various groups contributing to the problem in West Africa and the Sahel:

The Sahel

The Sahel is an expansive region, encompassing the territories of Burkina Faso, Niger, Mali, Mauritania, and Chad. Islamic extremist groups operating in this region have included the likes of Ansar al-Dine, al-Murabitun, and AQIM-Sahel, all of whom shared the common goal of widespread institutionalization of Islamic law. In March 2017, these groups merged, spawning a new group, Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen. This new terrorist outfit is now suspected of carrying out the aforementioned cafe attack in Burkina Faso. Additionally, there is a growing ISIS presence in the region, though their expansion is tempered by Al Qaeda’s near-total dominance of the Sahel’s jihadi scene.

But of these Sahel states, Mali has been the most instrumental staging ground for attacks on Western targets in neighboring states. Here, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and their affiliates remain dominant, their presence solidified in the wake of a military coup d’état in 2012 that drastically weakened the Malian army’s capacity to combat the growing Islamic extremist presence in the country’s northern provinces, an area that sits conveniently at the axis of a porous borderland straddling Niger, Algeria, Burkina Faso, and Mauritania. Such positioning provides these groups with bountiful points of egress and entry through which they can strike targets in any number of states at any given time.

But while the threat posed by these Sahel-based groups is certainly a violent one, there is also a significant threat of kidnapping in the region, most of which are retaliatory acts for the post-coup, French and African military intervention in Mali. Targets often included individuals related to the UN peacekeeping initiative in Mali, MINUSMA, or those who represent Western interests, such as humanitarian aid workers, diplomats, and tourists.

West Africa

The terror threat to West Africa is no less potent. Here, well-equipped groups such as AQIM and Boko Haram represent major challenges to a growing number of governments. In March 2016, AQIM launched attacks in the Ivory Coast in which gunmen opened fire on swimmers and diners on a popular beachfront in Bassam, killing 19. Further east, in Nigeria, Boko Haram has carried out consistent assaults on soft and state targets in the country’s northern states. There are also growing concerns of radicalization in Senegal, a comparatively stable and democratic state, where terror threatens to derail a budding tourism industry.

These groups differ significantly in their scope and operations. AQIM, as noted above, is more violently oriented toward Western targets, and shares the international scope and vision of its parent organization, Al-Qaeda. Boko Haram, for its part, is more focused on the destruction of the Nigerian state and the establishment of an Islamic caliphate. The group is therefore less inclined to declare a violent campaign against the wider West, making Boko Haram more synonymous with groups like the Afghan Taliban rather than Al-Qaeda.

Responding to the Threat

For the past four years, regional efforts have been led by France, whose goal is to fill the power vacuums left by major geopolitical events such as the fall of Muammar Qaddafi in Libya and the military coup in Mali. The United States has typically supported these efforts, providing diplomatic, financial, and intelligence support to French counterterrorism forces. However, in recent months the Trump administration has cast doubt on the future of a French Security Council resolution aimed at creating an African counterterrorism force in the Sahel. This initiative would, as the French argue, enable local forces to combat terrorism while minimizing the footprint of the United States and United Nations. However, doubts over the proposed resolution are great. The most significant stumbling block is how the force of 5,000 African soldiers and police will be funded.

The United States and Britain support, in principle, the commitment to raise African military capacity in the region. However, the five nation African anti-terrorism force – compiled of troops from Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger – would require American and UN funding at a time when President Trump is working to scale back US involvement with multilateral security operations in the region. The United States in now weighing the possibility of vetoing the motion at the UN Security Council.

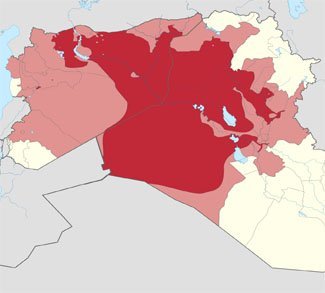

Such a move would be a mistake given the regional security context. Since the onset of the Arab Spring, the eyes of Western policymakers have been increasingly fixed on efforts to counter extremism and destabilization in Syria and the wider Middle East. Such tunnel vision has distracted from efforts to counter extremism is sub-Saharan Africa, where efforts are at risk of being fatally undermined. Indeed, Western policymakers would be negligent to beat back extremism in one part of the world, only to allow extremism to foment elsewhere.

The overarching objective must be to restrict the spread of regional destabilization and build African military capacity. Approval of the French Security Council resolution to fund Sahel security forces is a vital first step in improving the latter’s capacity to secure urban populations and extend their remit to increasingly remote areas where extremist groups are most concentrated. In doing so, Western powers must increase their intelligence-sharing capabilities with, and tactical support to, African security forces.

All of these are pressing issues for Western policymakers, and while ‘destabilization’ is indeed a nebulous threat, the fallout stemming from government failure to control its territories and populations is very real. Improving state capacity to address such failures will prove vital in disrupting the positive feedback loop that extremism threatens to exacerbate.